Bloomsbury Natural History

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2017 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in 2007 by New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd

This edition first published in 2017 by Bloomsbury

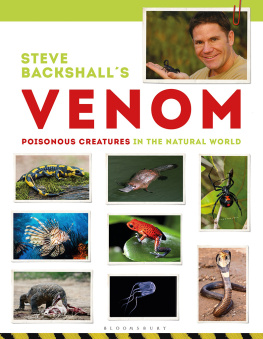

Copyright 2017, 2007 in text: Steve Backshall

Copyright 2017, 2007 in photographs: NHPA

Steve Backshall has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3026-2 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3027-9 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3028-6 (ePDF)

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

This book is dedicated to my parents, for a lifetime of selfless support and for introducing me to the wonderful worlds of wildlife and exploration.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

BRUTAL TOXIN

CHAPTER TWO

EUROPE

CHAPTER THREE

NORTH AMERICA

CHAPTER FOUR

LATIN AMERICA

CHAPTER FIVE

AFRICA

CHAPTER SIX

AUSTRALASIA

CHAPTER SEVEN

ASIA

CHAPTER EIGHT

THE FUTURE FOR VENOMOUS WILDLIFE

CHAPTER ONE

BRUTAL TOXIN

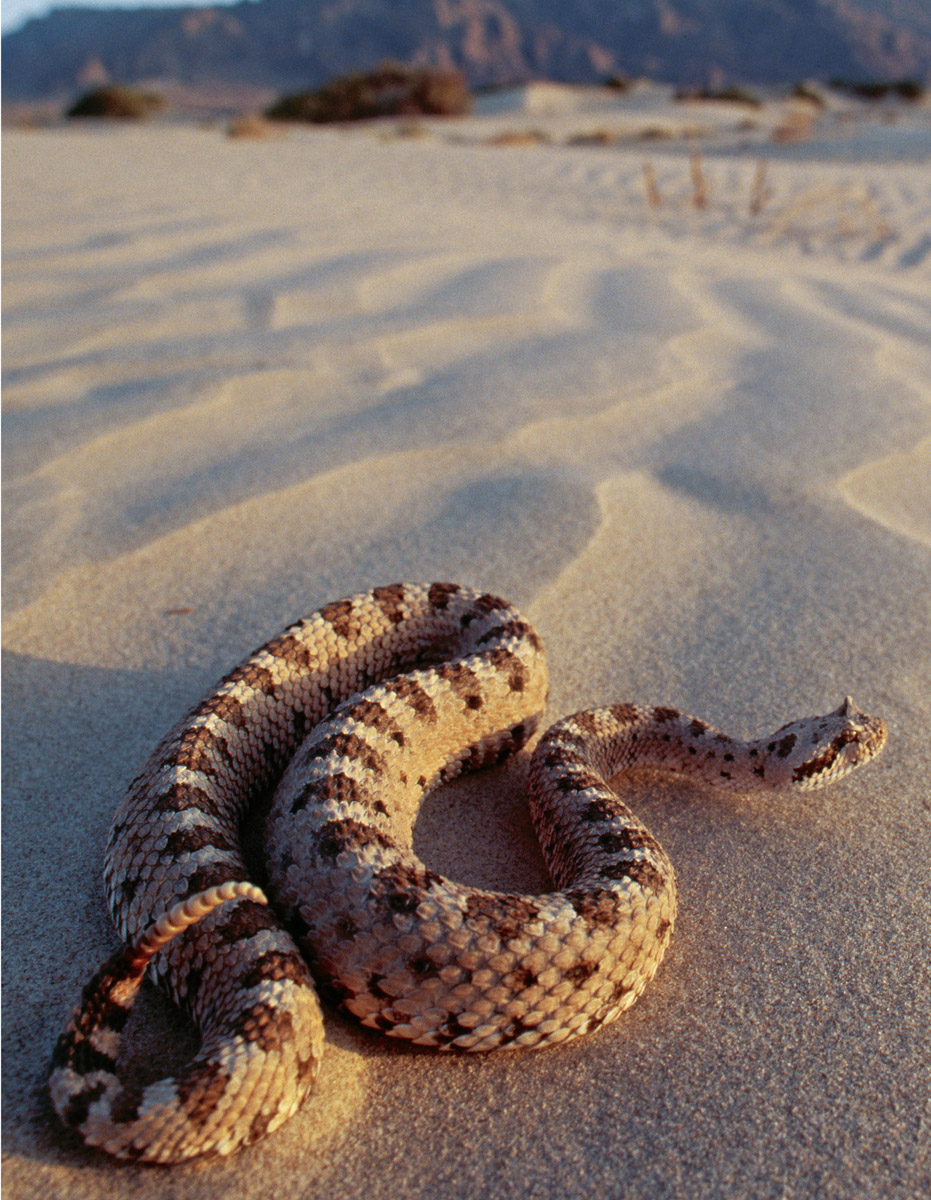

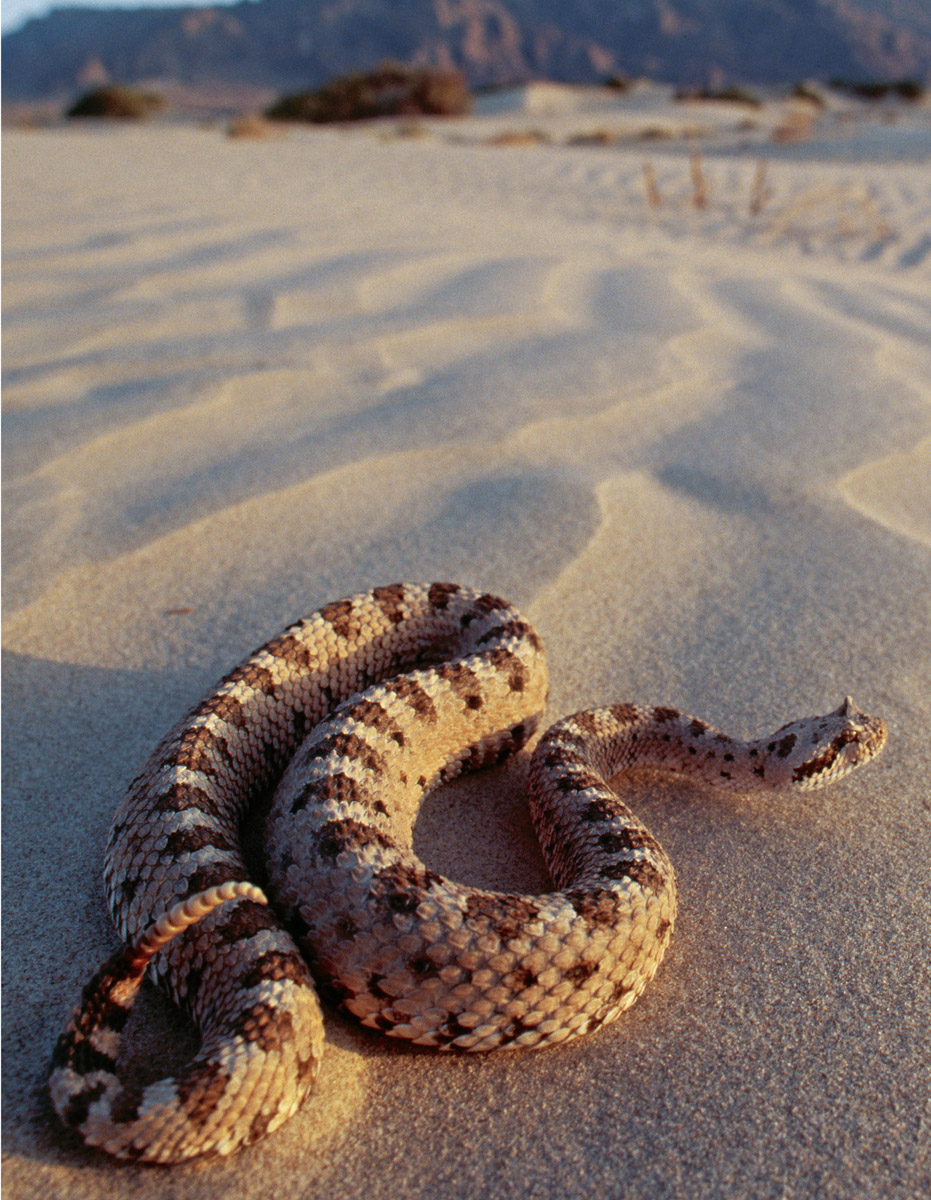

The fang barely pierced the skin, no more than a faint scratch, yet a teaspoon of virulent, yellowy fluid already surges through the veins, blossoming through the body like ink billowing in a glass of water. Teasing its way into the arteries, the venom begins to wreak havoc, a toxic lava flow let loose in the bloodstream. Complex molecules in the venom assault the bodys communication centres, pulsating down the nerves. Under such bombardment, the neurons collapse in confusion, causing breathing and heartbeat to stutter. The serpent recoils, and awaits the inevitable.

A Sidewinder (Crotalus cerastes) searches for prey.

INTRODUCTION

Deep in the jungle on a recent expedition in Borneo, a fellow naturalist caught a tiny reptile that he mistook for a species of harmless kukri snake. He realized too late that it was actually a Coral Snake, Maticora intestinalis, a relative of the cobras; too late, because it had just bitten him on the finger. An internationally renowned herpetologist who was with us started running around, screaming out in loud panic that the naturalists days were numbered, and that he only had a few horribly painful minutes left to live. Quite apart from the fact that this is without doubt the worst possible way to treat a person who has just been bitten by anything venomous, it also couldnt be further from the truth. On average you have a 90 per cent chance of surviving bites from cobras and seasnakes, with death in those few cases not happening until 515 hours after the victim has been bitten. (Vipers have a more variable mortality rate of 115 per cent, and as much as 48 hours after the bite.)

As it happened, my naturalist pal had received a dry bite, ie. no venom had been injected, and he suffered no ill effects at all (it was a close call though he nearly asked his girlfriend to marry him in the time he thought he was doomed!). Even if venom IS injected, it still doesnt mean the end of ones days. Whilst on a recent filming trip in Thailand, I stayed with a snake dancer who had been bitten no fewer than NINETEEN times by the dreaded King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), and was still alive to tell the tale. And in Australia, where any bushman will tell you the snakes are deadly enough to kill a herd of buffalo, fewer than two people a year are lost to snakebite.

The ultimate champion of champions, Phyllobates terribilis is so toxic that its believed to have enough poison to kill ten men. This potent load is all synthesized from insects (probably Choresine Beetles), which in turn have sequestered alkaloids from the plants they eat.

The point Im trying to make with these facts and figures is that the actual dangers from venomous creatures are massively overstated even by those who should know better. I feel almost guilty writing this book; the vast majority of animals in here are of absolutely zero potential danger to human beings, now or ever, and even the most dangerous of species... well, youre less likely to get killed by one than you are to be run over by a milk float!

Yet despite the realities, venom and the animals that use it have been an endless fascination to me ever since I was a youngster. Its probably the potential visceral power, the possibility of terrible harm, that is so morbidly absorbing. I guess its the small boy in me thats writing this now and hoping that someone else feels the same wonder at the extraordinary lethal harpoon of the cone shell, the dart frog that looks like a Faberg jewel, and the fabled menace of the mamba.

DEFINITIONS

Outside of the lab and the classroom, the terms toxin, venom and poison are used carelessly and interchangeably to mean any kind of unpleasant natural chemical. However, they actually mean rather different things. Potentially dangerous toxins exist in both venomous and poisonous animals, but its the way in which the toxin is delivered that differs. Put simply, venom is injected whilst poison is ingested. Venomous animals have active systems for delivering their vicious payload, injecting toxins into a threaten ing predator or their prey through the use of fangs, claws, spines, spurs or any other sharp body part that is hollow, grooved or able to break the skin.