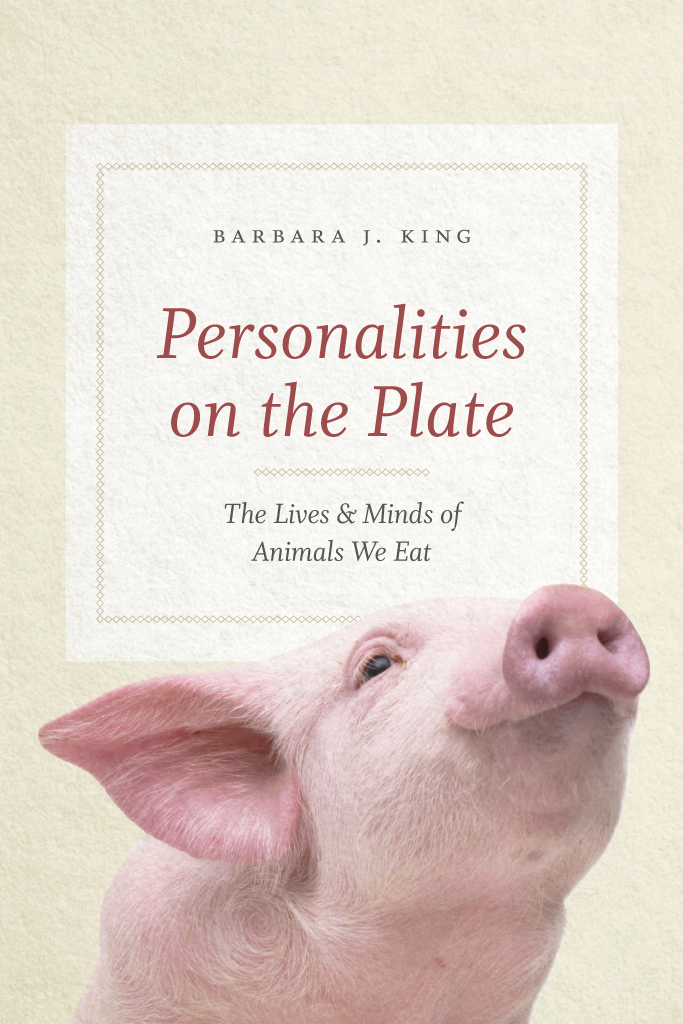

Personalities on the Plate

The Lives and Minds of Animals We Eat

Barbara J. King

The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by Barbara J. King

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-19518-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-19521-6 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226195216.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: King, Barbara J., 1956 author.

Title: Personalities on the plate : the lives and minds of animals we eat / Barbara J. King.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016034780| ISBN 9780226195186 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226195216 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Food animalsSocial aspects. | Animal behavior.

Classification: LCC SF . K553 2017 | DDC 636.088/3dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016034780

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Charlie and Sarah

Always

The meat defiant, the meat insurgent, the meat fighting, Sofia thought. The meat in full cry....

Sitting by his head, she ran her hand along the fine soft fur of his cheek, over and over, while his body cooled and she paid the awful debt of love.

Maria Doria Russell, Children of God (sequel to The Sparrow)

Contents

We never seem to doubt that an animal acting hungry feels hungry. What reason is there to disbelieve that an elephant who seems happy is happy?

Carl Safina, Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel

The barbecued meat (nyama chama in Swahili) kept coming, carved right at our table. The pork and chicken were familiar enough, the rabbit and venison less so. Ox and zebra? To our eyes, exotic.

It was a cool Nairobi night in 1986, and my mother, Elizabeth; my Aunt Barbara, for whom I am named; one of my dearest college friends, Jim; and I had ventured to Carnivore Restaurant. Upon arrival, our little group was ushered to an outdoor patio. At first I worried that the air might be too chill, but how gloriously inviting it was to dine under open skies! The staff even provided tableside braziers to warm us.

Waiter after waiter came with meat on huge skewers, my mother wrote that night in her travel diary, a tiny notebook that now, after her death, I cherish along with her other keepsakes. They removed pieces or cut chunks out of huge pieces of meat, 10 kinds altogether. Im pretty sure we ate antelope too. Kudu was once served at Carnivore-Nairobi and remains on the menu at Carnivore-Johannesburg in South Africa. Despite the Kenyan government ban on serving game, ostrich and crocodile are brought to diners tables even now at Carnivore-Nairobi.

Back in 1986, I was living several hours drive south of Kenyas capital in Amboseli National Park, near the border with Tanzania. From my backyard, which often hosted wildebeest and zebra and sometimes elephant, the volcanic peaks of Mount Kilimanjaro loomed big and beautiful. At Carnivore, I was enjoying a brief holiday in the midst of a fourteen-month monkey-watching stint. My project focused on how infant baboons learn what fruits, grasses, and tubers to eat as they roam the savannah with family members and group-mates. For a graduate student in anthropology, carrying out this research at Amboseli was a dream come true. Enthralled not just with the primates that the National Science Foundation had funded me to study, but also with the parks elephants, lions, Cape buffalo, ostrich, warthogs, and marabou storks, I animal-watched purely for fun whenever I could steal some time from science. To sit quietly and try to work out who was friends or rivals with whom, or what the animals sounds and body language meant, was pure joy. On my rare days off, when I wasnt in Nairobi to Xerox and mail data back home (no scanning and emailing in those days!), I would sit outdoors and soak up what the African plains had to teach me.

And yet at Carnivore, sitting outdoors with loved ones who had endured a twenty-two-hour Pan Am flight from New York in order to visit me, that sense of wonder and connection with other animals fell away. I didnt see animals on the plates set before us, I saw (and smelled) meatand a chance for an animal-tasting adventure that would yield a good story back home.

An invisible toggle switch had flipped in my brain, one that I wasnt aware of, much less able to reflect upon: Barbara the avid observer of animals became Barbara the voracious eater of animals. That memory makes me uncomfortable now, especially because I enthusiastically consumed individuals of the very same species I so loved to observe running wild in Amboseli.

Of course, the evening at Carnivore wasnt the first, or last, time I did something like that. How many barnyard or ocean animals did I avidly watch or read about, then eat, over the years? That peculiar duality comes easily to our species. When touring Yellowstone, the 2.2-million-acre national park that spills across the borders of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, my foremost passion is bison-watching. For hours, my husband and I observe the heavy-shouldered males as with raw power they engage femalesor their big bull rivals for those females. The females themselves huddle with their youngsters, who romp away from the moms to play in the meadow. In Yellowstones Lamar Valley, we once stood pressed against our car as a bison herd of more than a hundred individuals flowed close around us. (To actively approach wild bison is a mistake that people may pay for by being tossed in the air by sharp horns, sometimes fatally; in our once-in-a-lifetime experience, the bison chose to walk calmly past us.) Usually, we watch from inside a car stationed in a snaking length of other wildlife enthusiasts vehicles. If we break for dinner at a park restaurant, happily sharing our descriptions and photographs of that days most majestic animals, right there on the menu are the bisons ranched counterparts. We always select the pasta.

On another trip, leaving Everglades National Park in south Florida, we drove roads that cut through the greater Everglades ecosystem. We flashed past signs for roadside family businesses that tout airboat tours: See beautiful alligators in the morning! Enjoy gator nuggets at midday! This kind of thing, what Ive called our peculiar duality in relation to other animals, is ubiquitous. Aquarium-goers admire the tentacle beauty of an octopus, the planets smartest invertebrate, then order grilled baby octopus at lunch. Parents read their children bedtime stories starring sweet chicks or plucky pigs only hours after having served chicken or pork for dinner.

Psychologist Hal Herzog titled his book about our relationship with other animals Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat, and nails it in a sentence: Human attitudes toward other species are inevitably paradoxical and inconsistent. We love the dog and eat the pig, or, we love the bison and eat the bison. Who exactly

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).