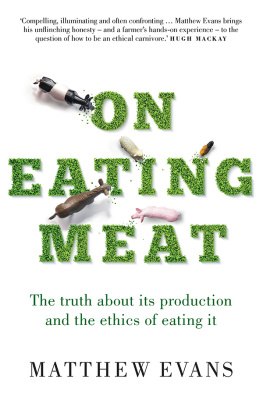

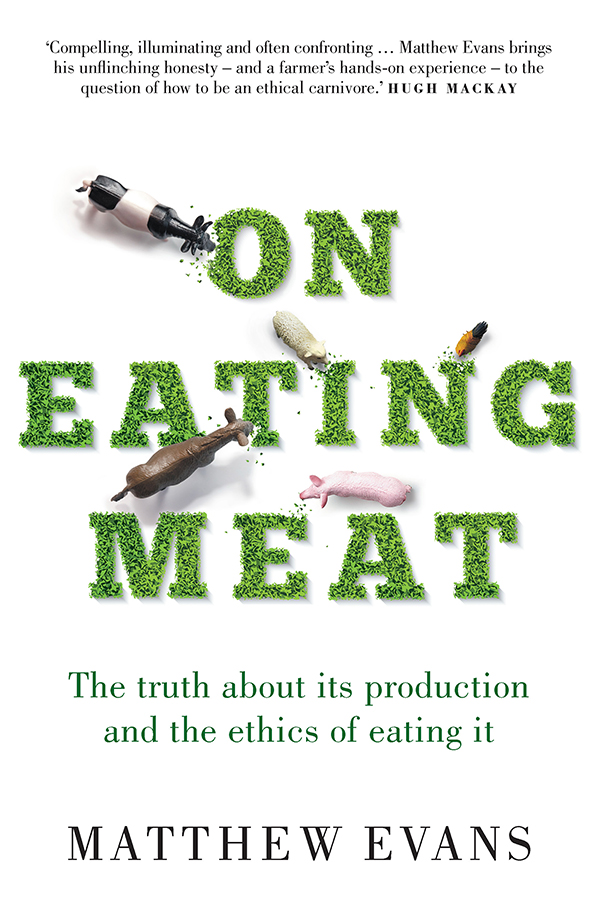

Praise for On Eating Meat

Hugh Mackay: Compelling, illuminating and often confronting, On Eating Meat is a brilliant blend of a gastronomes passion with forensic research into the sources of the meat we eat. Matthew Evans brings his unflinching honesty and a farmers hands-on experience to the question of how to be an ethical carnivore.

Richard Glover: Intellectually thrilling a book that challenges both vegans and carnivores in the battle for a new ethics of eating. This book will leave you surprised, engrossed and sometimes shocked whatever your food choices.

Anton Vikstrom, Good Life Permaculture: Matthew Evans fearlessly investigates where our food comes from and the hidden impacts of our industrial food system. If you eat meat, read this book.

Professor Andy Lowe, Director of Agrifood and Wine, University of Adelaide: Insightful, well-researched and highly readable, Matthew Evans new book On Eating Meat presents an honest and challenging assessment of the livestock industry and the ethical and environmental issues surrounding our consumption of meat this book equips the reader with the knowledge to get beyond the entrenched opinions of its topic area, and allows us to decide whether and what type of meat we wish to consume, and with what consequences for the future.

Alex Elliott-Howery, Cornersmith: This is the most important food book Ive read in years. Not just for meat lovers or vegans, it should be read by anyone who eats food. When I finished this book I felt informed, connected and empowered to make better decisions about how I shop, cook and eat.

Published in 2019 by Murdoch Books, an imprint of Allen & Unwin

Copyright 2019 by Matthew Evans

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Murdoch Books Australia

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest NSW 2065

Phone: +61 (0)2 8425 0100

murdochbooks.com.au

Murdoch Books UK

Ormond House, 2627 Boswell Street,

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: +44 (0) 20 8785 5995

murdochbooks.co.uk

For corporate orders and custom publishing contact our business development team at

ISBN 978 1 76063 769 9 Australia

ISBN 978 1 91163 221 4 UK

eISBN 978 1 76087 161 1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover design by Design By Committee

Contents

Its, um, a bit hard on the nose, I say, trying to be polite.

Smells like money, says the feedlot owner. The chicken farmer. The pig farm manager.

And that, at its heart, is the difference between them and me. I smell ammonia. Something that hits you high and hard in the nostrils and causes an almost involuntary gag. I smell an extraordinary amount of manure, rotting in the sun, or the shed, or the straw. A smell so bad that I have to throw my clothes away after the visit. A smell so toxic that the locals forbid the workers from entering the local caf after work until theyve changed clothes and their partners refuse to allow work clothes in the house. Its the smell of intensive animal confinement, one that can lead to ammonia levels in pig sheds to be over four times the recommended 25 parts per million set by Safe Work Australia.

The saying, Smells like money, is the difference between the owners of these farms and me. I smell toxins. They smell profit.

Intensive animal farming is the way we largely do things in Australia, and indeed in many countries around the world. Its the way the supermarket $5 roast chicken reaches your shopping basket. How an $8 a kilo ham makes its way to your festive table each Christmas. Why you can enjoy consistently tender beef, despite the cattle being run in feedlots, completely lacking in grass. Its a long way from the idyllic image consumers have of animals grazing contentedly on lush green grass. And its a long, long way from my little farm in rural Tasmania, where what matters to me is stewardship of the land, the instinctual freedoms of the animals in my care, and an openness to consumers about what we do.

I have many conflictions about my meat eating. Trained as a chef, I later became a food writer and then restaurant critic, more interested in the pedigree of the chefs than the origins of their ingredients. The ethics of food production came secondary to the need to eat a lot (I was very active, and skinny, when young). Any interest in the morality of what we consume also came after the desire to eat food that tasted great.

Yes, for a while after leaving school, like many I dabbled in vegetarianism, vaguely concerned with how the animals I ate were reared, but more interested in the quality and cost of the meat I had been able to afford. And like most who dabble in such diets, I didnt stick to it once the pay cheques started to roll in, and the quality of the meat I could afford improved.

Yet niggles remained in my mind: rumours of intensive farms, of animals denied the ability to express their basic instincts; suggestions that farming of animals wasnt as ideal as wed all presumed.

Later, wondering why some food tasted better, I ventured onto more farms, and discovered that not all animals are reared the same way. Driven by pursuit of quality, I started to glimpse the ugly truth about what is done in our name on farms across the nation. And eventually, thinking it would be the ultimate way to actually know and trust what you eat, I started farming myself.

A decade later, our family is now growing pretty much everything that hits the table when it comes to fruit, vegetables, dairy and meat. In the process, Ive discovered how little I once knew, and how much there is still to learn. About the land, about animals. About those who grow food for the rest of the nation to consume. In the process Ive made a documentary on the origins of our meat, For the Love of Meat, for SBS television, and been to some of the more intensive farms across the land. And what Ive discovered is that I dont want to live on a farm that smells like money.

Lets be clear. I am no angel. Animals have died because of my negligence. Disease has caused unnecessary suffering at my hands. When it comes to the livestock in my care, I am no sage, and am not always as good as I believe I should be. I fail my own standards again and again, when it gets down to the reality of things I do on my farm.

But what of these people who I met on my travels, who rear animals on behalf of the meat eaters of my beloved nation? Who talk about the pungent, nose-wrinkling, brain-stifling smell of the manure of their farms as smelling like money? Do they fail the standards of those who trust them to breed, rear and dispatch the animals in their care the animals they look after on behalf of meat eaters around the country? Do they fail, as a group, to meet your expectations, day on day, year on year? Are they accountable to you, if youre a meat eater, for the treatment of the animal, and the environment, as youd like them to be for the price you are paying?