First Mariner Books edition 2013

Copyright 2012 by Jonathan Gottschall

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Gottschall, Jonathan.

The storytelling animal: how stories make us human / Jonathan Gottschall.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-547-39140-3

ISBN 978-0-544-00234-0 (pbk.)

1. Storytelling. 2. Literature and science. I. Title.

GR72.3.G67 2012

808.5'43dc23

2011042372

eISBN 978-0-547-64481-3

v2.0413

Blizzard Entertainment and The World of Warcraft are registered trademarks of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc.

To Abigail and Annabel, brave Neverlanders

God made Man because He loves stories.

ELIE WIESEL, The Gates of the Forest

Preface

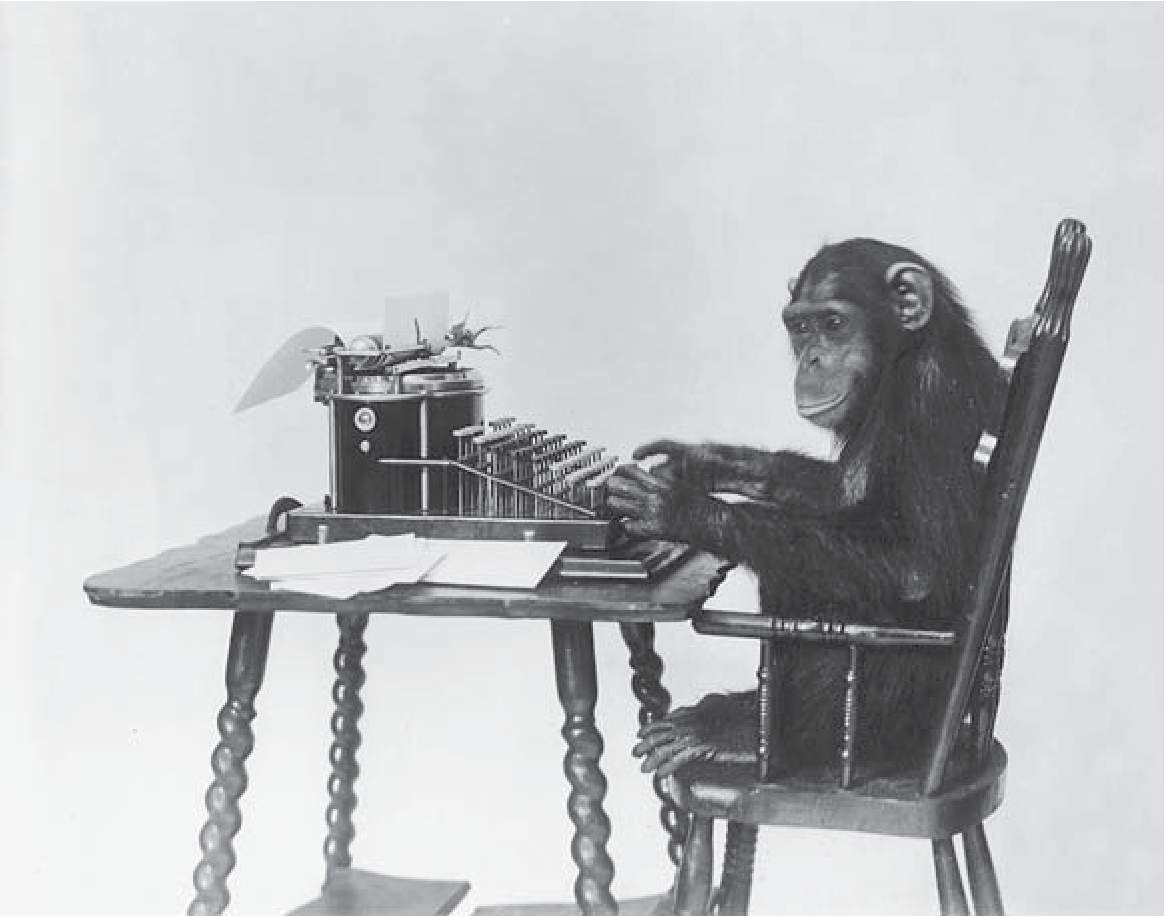

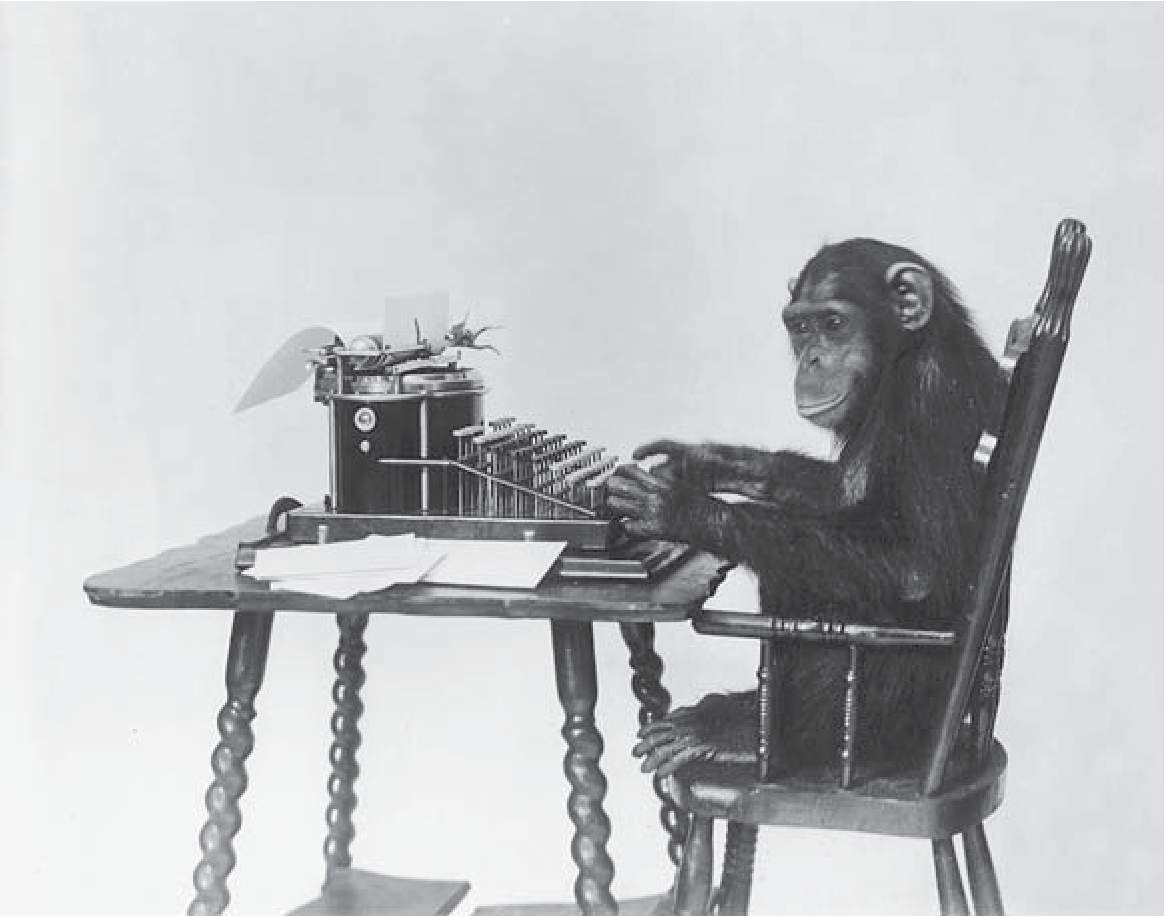

Statisticians agree that if they could only catch some immortal monkeys, lock them up in a room with a typewriter, and get them to furiously thwack keys for a long, long time, the monkeys would eventually flail out a perfect reproduction of Hamletwith every period and comma and sblood in its proper place. It is important that the monkeys be immortal: statisticians admit that it will take a very long time.

Others are skeptical. In 2003, researchers from Plymouth University in England arranged a pilot test of the so-called infinite monkey theorypilot because we still dont have the troops of deathless supermonkeys or the infinite time horizon required for a decisive test. But these researchers did have an old computer, and they did have six Sulawesi crested macaques. They put the machine in the monkeys cage and closed the door.

The monkeys stared at the computer. They crowded it, murmuring. They caressed it with their palms. They tried to kill it with rocks. They squatted over the keyboard, tensed, and voided their waste. They picked up the keyboard to see if it tasted good. It didnt, so they hammered it on the ground and screamed. They began poking keys, slowly at first, then faster. The researchers sat back in their chairs and waited.

A whole week went by, and then another, and still the lazy monkeys had not written Hamlet, not even the first scene. But their collaboration had yielded some five pages of text. So the proud researchers folded the pages in a handsome leather binding and posted a copyrighted facsimile of a book called Notes Towards the Complete Works of Shakespeare on the Internet. I quote a representative passage:

Ssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssnaaaaaaaaa

Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaasssssssssssssssssfssssfhgggggggsss

Assfssssssgggggggaaavmlvvssajjjlssssssssssssssssa

The experiments most notable discovery was that Sulawesi crested macaques greatly prefer the letter s to all other letters in the alphabet, though the full implications of this discovery are not yet known. The zoologist Amy Plowman, the studys lead investigator, concluded soberly, The work was interesting, but had little scientific value, except to show that the infinite monkey theory is flawed.

In short, it seems that the great dream of every statisticianof one day reading a copy of Hamlet handed over by an immortal supermonkeyis just a fantasy.

But perhaps the tribe of statisticians will be consoled by the literary scholar Jiro Tanaka, who points out that although Hamlet wasnt technically written by a monkey, it was written by a primate, a great ape to be specific. Sometime in the depths of prehistory, Tanaka writes, a less than infinite assortment of bipedal hominids split off from a not-quite infinite group of chimp-like australopithecines, and then another quite finite band of less hairy primates split off from the first motley crew of biped. And in a very finite amount of time, [one of] these primates did write Hamlet.

And long before any of these primates thought of writing Hamlet or Harlequins or Harry Potter storieslong before these primates could envision writing at allthey thronged around hearth fires trading wild lies about brave tricksters and young lovers, selfless heroes and shrewd hunters, sad chiefs and wise crones, the origin of the sun and the stars, the nature of gods and spirits, and all the rest of it.

Tens of thousands of years ago, when the human mind was young and our numbers were few, we were telling one another stories. And now, tens of thousands of years later, when our species teems across the globe, most of us still hew strongly to myths about the origins of things, and we still thrill to an astonishing multitude of fictions on pages, on stages, and on screensmurder stories, sex stories, war stories, conspiracy stories, true stories and false. We are, as a species, addicted to story. Even when the body goes to sleep, the mind stays up all night, telling itself stories.

This book is about the primate Homo fictus (fiction man), the great ape with the storytelling mind. You might not realize it, but you are a creature of an imaginative realm called Neverland. Neverland is your home, and before you die, you will spend decades there. If you havent noticed this before, dont despair: story is for a human as water is for a fishall-encompassing and not quite palpable. While your body is always fixed at a particular point in space-time, your mind is always free to ramble in lands of make-believe. And it does.

Yet Neverland mostly remains an undiscovered and unmapped country. We do not know why we crave story. We dont know why Neverland exists in the first place. And we dont know exactly how, or even if, our time in Neverland shapes us as individuals and as cultures. In short, nothing so central to the human condition is so incompletely understood.

The idea for this book came to me with a song. I was driving down the highway on a brilliant fall day, cheerfully spinning the FM dial. A country music song came on. My usual response to this sort of catastrophe is to slap franticly at my radio in an effort to make the noise stop. But there was something particularly heartfelt in the singers voice. So, instead of turning the channel, I listened to a song about a young man asking for his sweethearts hand in marriage. The girls father makes the young man wait in the living room, where he stares at pictures of a little girl playing Cinderella, riding a bike, and running through the sprinkler with a big popsicle grin / Dancing with her dad, looking up at him. The young man suddenly realizes that he is taking something precious from the father: he is stealing Cinderella.

Before the song was over, I was crying so hard that I had to pull off the road. Chuck Wickss Stealing Cinderella captures something universal in the sweet pain of being a father to a daughter and knowing that you wont always be the most important man in her life.

I sat there for a long time feeling sad but also marveling at how quickly Wickss small, musical story had melted mea grown man, and not a weeperinto sheer helplessness. How odd it is, I thought, that a story can sneak up on us on a beautiful autumn day, make us laugh or cry, make us amorous or angry, make our skin shrink around our flesh, alter the way we imagine ourselves and our worlds. How bizarre it is that when we experience a storywhether in a book, a film, or a songwe allow ourselves to be invaded by the teller. The story maker penetrates our skulls and seizes control of our brains. Chuck Wicks was in my headsquatting there in the dark, milking glands, kindling neurons.

Next page