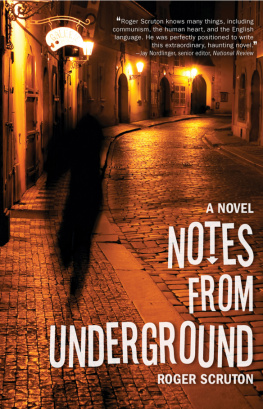

Roger Scruton - Beauty

Here you can read online Roger Scruton - Beauty full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: ePubLibre, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Beauty

- Author:

- Publisher:ePubLibre

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beauty: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Beauty" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Beauty — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Beauty" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Roger Scruton explores this timeless concept, asking what makes an objecteither in art, in nature, or the human formbeautiful. This compact volume is filled with insight. Can there be dangerous beauties, corrupting beauties, and immoral beauties? Scruton insists that beauty is a real and universal value, one anchored in our rational nature, and that the sense of beauty has an indispensable part to play in shaping the human world.

Roger Scruton

ePub r1.0

Titivillus 09.04.16

Ttulo original: Beauty

Roger Scruton, 2010

Editor digital: Titivillus

ePub base r1.2

Beauty can be consoling, disturbing, sacred, profane; it can be exhilarating, appealing, inspiring, chilling. It can affect us in an unlimited variety of ways. Yet it is never viewed with indifference: beauty demands to be noticed; it speaks to us directly like the voice of an intimate friend. If there are people who are indifferent to beauty, then it is surely because they do not perceive it.

Yet judgements of beauty concern matters of taste, and maybe taste has no rational foundation. If so, how do we explain the exalted place of beauty in our lives, and why should we lament the factif fact it isthat beauty is vanishing from our world? And is it the case, as so many writers and artists since Baudelaire and Nietzsche have suggested, that beauty and goodness may diverge, so that a thing can be beautiful precisely in respect of its immorality?

Moreover, since it is in the nature of tastes to differ, how can a standard erected by one persons taste be used to cast judgement on anothers? How, for example, can we pretend that one type of music is superior or inferior to another when comparative judgements merely reflect the taste of the one who makes them?

That familiar relativism has led some people to dismiss judgements of beauty as purely subjective. No tastes can be criticized, they argue, since to criticize one taste is simply to give voice to another; hence there is nothing to learn or to teach that could conceivably deserve the name of criticism. This attitude has put in question many of the traditional disciplines in the humanities. The studies of art, music, literature and architecture, freed from the discipline of aesthetic judgement, seem to lack the firm anchor in tradition and technique that enabled our predecessors to regard them as central to the curriculum. Hence the current crisis in the humanities: is there is any point in studying our artistic and cultural inheritance, when the judgement of its beauty has no rational grounds? Or if we do study it, should this not be in a sceptical spirit, by way of questioning its claims to objective authority, and deconstructing its posture of transcendence?

When each year the Turner prize, founded in memory of Englands greatest painter, is awarded to yet another bundle of facetious ephemera, is this not proof that there are no standards, that fashion alone dictates who will and who will not be rewarded, and that it is pointless to look for objective principles of taste or a public conception of the beautiful? Many people answer yes to those questions, and as a result renounce the attempt to criticize either the taste or the motives of the Turner-prize judges.

In this book I suggest that such sceptical thoughts about beauty are unjustified. Beauty, I argue, is a real and universal value, one anchored in our rational nature, and the sense of beauty has an indispensable part to play in shaping the human world. My approach to the topic is not historical, neither am I concerned to give a psychological, still less an evolutionary, explanation of the sense of beauty. My approach is philosophical, and the principal sources for my argument are the works of philosophers. The point of this book is the argument that it develops, which is designed to introduce a philosophical question and to encourage you, the reader, to answer it.

Some parts of this book started life elsewhere, and I am grateful to the editors of the British Journal of Aesthetics, the Times Literary Supplement, Philosophy and City Journal for permission to re-work material that has already appeared in their pages. I am also grateful to Christian Brugger, Malcolm Budd, Bob Grant, John Hyman, Anthony OHear and David Wiggins, for helpful comments on previous drafts. They saved me from many errors, and I apologize for the errors that remain, which are all my fault.

R.S.

Sperryville, Virginia,

May 2008.

Judging Beauty

We discern beauty in concrete objects and abstract ideas, in works of nature and works of art, in things, animals and people, in objects, qualities and actions. As the list expands to take in just about every ontological category (there are beautiful propositions as well as beautiful worlds, beautiful proofs as well as beautiful snails, even beautiful diseases and beautiful deaths), it becomes obvious that we are not describing a property like shape, size or colour, uncontroversially present to all who can find their way around the physical world. For one thing: how could there be a single property exhibited by so many disparate types of thing?

Well, why not? After all, we describe songs, landscapes, moods, scents and souls as blue: does this not illustrate the way in which a single property can occur under many categories? No, is the answer. For while there is a sense in which all those things can be blue, they cannot be blue in the way that my coat is blue. In referring to so many types of thing as blue, we are using a metaphorone that requires a leap of the imagination if it is to be rightly understood. Metaphors make connections which are not contained in the fabric of reality but created by our own associative powers. The important question about a metaphor is not what property it stands for, but what experience it suggests.

But in none of its normal uses is beautiful a metaphor, even if, like many a metaphor, it ranges over indefinitely many categories of object. So why do we call things beautiful? What point are we making, and what state of mind does our judgement express?

The true, the good and the beautiful

There is an appealing idea about beauty which goes back to Plato and Plotinus, and which became incorporated by various routes into Christian theological thinking. According to this idea beauty is an ultimate valuesomething that we pursue for its own sake, and for the pursuit of which no further reason need be given. Beauty should therefore be compared to truth and goodness, one member of a trio of ultimate values which justify our rational inclinations. Why believe p? Because it is true. Why want x? Because it is good. Why look at y? Because it is beautiful. In some way, philosophers have argued, those answers are on a par: each brings a state of mind into the ambit of reason, by connecting it to something that it is in our nature, as rational beings, to pursue. Someone who asked why believe what is true? or why want what is good? has failed to understand the nature of reasoning. He doesnt see that, if we are to justify our beliefs and desires at all, then our reasons must be anchored in the true and the good.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Beauty»

Look at similar books to Beauty. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Beauty and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.