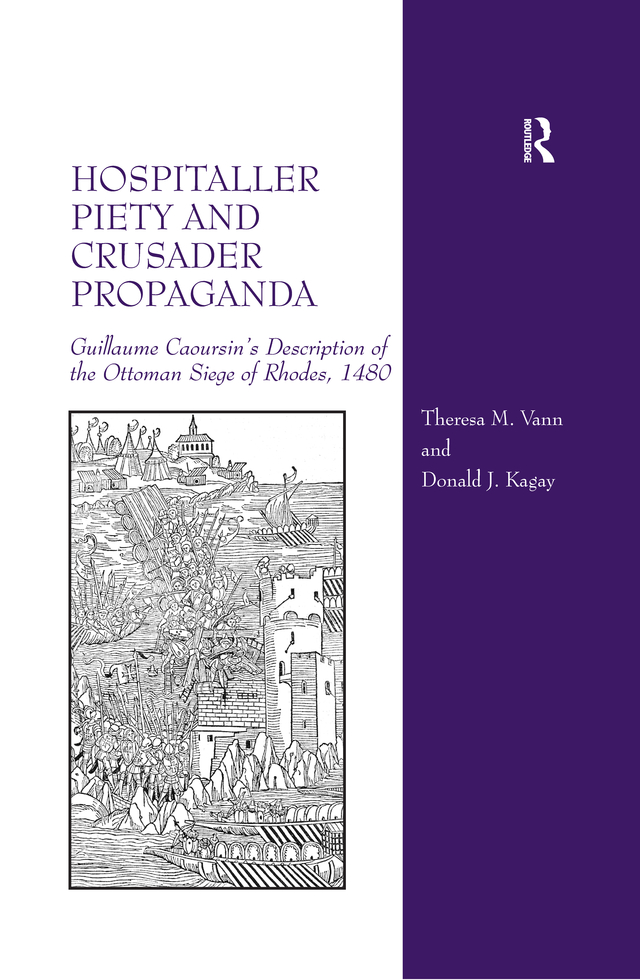

HOSPITALLER PIETY AND CRUSADER PROPAGANDA

Hospitaller Piety and Crusader Propaganda

Guillaume Caoursins Description of the Ottoman Siege of Rhodes, 1480

Theresa M. Vann and Donald J. Kagay

First published 2015 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Taylor & Francis

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2015 Theresa M. Vann and Donald J. Kagay

Theresa M. Vann and Donald J. Kagay have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Vann, Theresa M.

Hospitaller piety and crusader propaganda: Guillaume Caoursins description of the

Ottoman siege of Rhodes, 1480 /by Theresa M. Vann and Donald J. Kagay.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7546-3741-7 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Rhodes (Greece)--History--Siege, 1480. 2. Rhodes (Greece)--History--Siege, 1480-

Sources. 3. Caoursin, Guillaume, 1501. I. Kagay, Donald J. II. Title.

DF901.R42V36 2015

949.5'87--dc23

2014043571

ISBN 9780754637417 (hbk)

Contents

Map of Rhodes in the Eastern Mediterranean, showing

Hospitaller possessions in the Dodecanese |

The remains of the tower of St. Nicholas and the

entry of the Mandraki |

AOM 76, f. 35r, entry recording Caoursins official

account of the siege |

Erhard Reuwich, Rhodes (1484), from Bernhard von

Breydenbach, Peregrinationes in Terram Sanctam

(Mainz: Reuwich, 1486) |

Fifteenth-century image of Rhodes from the

Nuremburg Chronicle (Nuremburg: Anton Koberger,

printer, 1493), f. xxviv |

The first folio of the 1480 Ratdolt edition of

Caoursins Descriptio |

The execution of Master George. From Rhodiorum historia

(Ulm, 1496) |

In the spring and summer of 1480, an Ottoman fleet besieged the main convent of the Order of the Hospital located on the island of Rhodes. The Hospitallers, under the command of Master Pierre d'Aubusson, resisted the siege until the arrival of a fleet from Sicily forced the Ottoman Turks to withdraw. The vice-chancellor of the Order, a layman named Guillaume Caoursin, wrote an eyewitness account of the siege in Latin entitled Descriptio obsidione Rhodie. Before the end of the year, the printer Ernst Ratdolt published Caoursin's description of the siege of Rhodes in a twenty-four page booklet. The siege had sparked intense interest in western Europe, and two other eyewitnesses published their first-hand accounts. But these lacked the stamina of Caoursin's Descriptio, which enjoyed the institutional support of the Order of the Hospital. It became a best seller. Seven additional Latin editions were published before 1500, and it was translated into English, Italian, Danish, and German. Caoursin's history received wide acceptance as the official history of the events of the siege; less well appreciated were the motives behind its composition. The Order had commissioned the book to help it raise money to rebuild the city of Rhodes following the siege. Caoursin, who had been educated in Paris and was familiar with humanist scholarship on the continent, wrote the Descriptio to portray the Knights of the Hospital as the heroes of Christendom in the conflict against the Turks. Its publication spurred the sale of indulgences for the relief of Rhodes.

This book began when I recommended that the Malta Study Center purchase a copy of the Radolt edition of Guillaume Caoursin's Descriptio obsidione Rhodie, printed in Venice, 1480. It was my first major purchase as a curator, and I feverishly documented the reasons why the Center should buy the copy. It was easy to establish to the satisfaction of my director and a donor that it was an important work, one that should be in the collection of a center devoted to the history of the Order of the Hospital. Caoursin is frequently cited as a major source for the history of the Order, the later crusades in the eastern Mediterranean, and fifteenth-century warfare. After I established that our Library did not have a copy or reproduction in its possession, I found, to my surprise, that there was no modern Latin critical edition. In the absence of a readily-available Latin text, many researchers relied upon a fifteenth-century English translation that, through reprints and facsimiles, was more readily available than the Latin text. Even if scholars had access to the original published editions, they had difficulty reading the typeface or appreciating the challenges posed by incunabula.

It seemed to me that a new Latin edition of Caoursin, combined with a modern English translation, would be useful for students and scholars of the fifteenth century. After I began work, however, I realized that Caoursin's Descriptio did not simply augment the archival records. It was designed and composed to help the Order of the Hospital raise money against the return of the Turkish fleet. Caoursin wrote it in 1480 as the official narrative for others to translate and incorporate into their own works. But it contained themes that Caoursin and the Hospitaller chancery had been developing for years to interpret the Order's activities in the Levant for Christian Europe. My planned volume grew to incorporate related texts that demonstrated the Order's use of historical writing in the service of propaganda. Some were magisterial charters that predated the siege, yet included rhetoric that appeared in Caoursin's Descriptio. Then there was Pierre d'Aubusson's own account of the siege, which some attributed to Caoursin; John Kay's familiar fifteenth-century English translation, which contained unsuspected yet significant interpolations; Ademar Dupuis' French eyewitness account that was modeled on Caoursin's text; and, for comparison, Jacobo Curte's independent testimony that presented a different interpretation of events.

Scrutiny of the Descriptio's publication history revealed that the Hospitallers purposefully disseminated the official history of the siege using the relatively new technology of printing. In comparison with other early printed books, Caoursin's work survives in numerous copies and editions. European priories commissioned print runs, and individual knights wanted a copy of the book for their own library. The Order recognized Caoursin's Descriptio as an essential part of its history, valued as an adjunct to the archival records maintained in the chancery. The volume of the Liber conciliorum for the year 1480 contains a note stating that Caoursin's printed book served as the official record of the siege because the Turkish attack had disrupted the chancery's work. The weapon was the trebuchet, which had been commonly used in medieval warfare but was becoming obsolete by the late fifteenth century. Vertt obviously did not recognize the word or the weapon.