Endless

Forms

Most

Beautiful

The New Science of Evo Devo

AND THE M AKING OF THE A NIMAL K INGDOM

Sean B. Carroll

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

Jamie W. Carroll * Josh P. Klaiss * Leanne M. Olds

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Little Wing by Jimi Hendrix. Copyright Experience Hendrix, LLC. Used by Permission. All Rights Reserved. Revolution 1: Words and Music by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Copyright 1968 Sony/ATV Songs LLC. Copyright Renewed. All Rights Administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Learning to Fly: Words and Music by Jeff Lynne and Tom Petty. 1991 EMI April Music Inc. and Gone Gator Music. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured. Used by Permission. Wonderful World: Written by Sam Cooke, Herb Alpert, and Lou Adler. Published by ABKCO Music, Inc. (BMI).

Copyright 2005 by Sean B. Carroll

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING-IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Carroll, Sean B.

Endless forms most beautiful: the new science of evo devo and the making of the

animal kingdom / Sean B. Carroll; with illustrations by Jamie W. Carroll, Josh P. Klaiss,

Leanne M. Olds.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-39-306971-6

1. Developmental geneticsPopular works. 2. Evolutionary geneticsPopular works. I. Title.

QH453.C37 2005

571.8'5dc22

2004029388

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For Jamie, Will, Patrick,

Chris, and Josh

Preface

Revolution #3

You say you want a revolution

Well, you know we all want to change the world.

You tell me that its evolution,

Well, you know we all want to change the world

You say you got a real solution

Well, you know wed all love to see the plan.

John Lennon and Paul McCartney

Revolution 1 (1968)

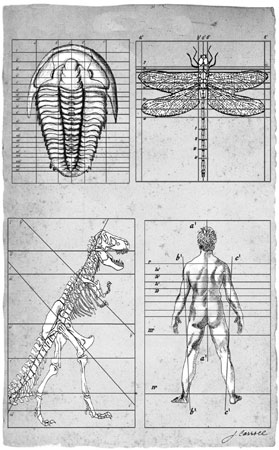

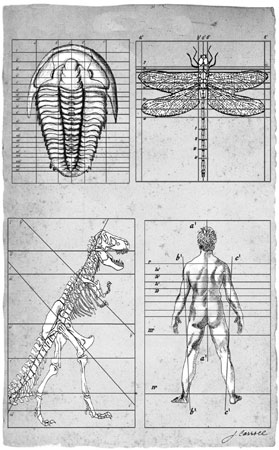

T HE PHYSICIST AND NOBEL laureate Jean Perrin once stated that the key to any scientific advance is to be able to explain the complex visible by some simple invisible. The two greatest revolutions in biology, those in evolution and genetics, were driven by such insights. Darwin explained the parade of species in the fossil record and the diversity of living organisms as products of natural selection over eons of time. Molecular biology explained how the basis of heredity in all species is encoded in molecules of DNA made of just four basic constituents. As powerful as these insights were, in terms of explaining the origin of complex visible forms , from the bodies of ancient trilobites to the beaks of Galapagos finches, they were incomplete. Neither natural selection nor DNA directly explains how individual forms are made or how they evolved.

The key to understanding form is development , the process through which a single-celled egg gives rise to a complex, multi-billion-celled animal. This amazing spectacle stood as one of the great unsolved mysteries of biology for nearly two centuries. And development is intimately connected to evolution because it is through changes in embryos that changes in form arise. Over the past two decades, a new revolution has unfolded in biology. Advances in developmental biology and evolutionary developmental biology (dubbed Evo Devo) have revealed a great deal about the invisible genes and some simple rules that shape animal form and evolution. Much of what we have learned has been so stunning and unexpected that it has profoundly reshaped our picture of how evolution works. Not a single biologist, for example, ever anticipated that the same genes that control the making of an insects body and organs also control the making of our bodies.

This book tells the story of this new revolution and its insights into how the animal kingdom has evolved. My goal is to reveal a vivid picture of the process of making animals and how various kinds of changes in that process have molded the different kinds of animals we know today and those from the fossil record.

I wrote the book with several kinds of readers in mind. First, for anyone interested in nature and natural history who takes delight in animals of the rain forest, reef, savannah, or fossil beds, there will be much said about the making and evolution of some of the most fascinating animals of the past and present. Second, for physical scientists, engineers, computer scientists, and others interested in the origins of complexity, this book tells the story of the enormous diversity that has been created from combining a small number of common ingredients. Third, for students and educators, I firmly believe that the new insights from Evo Devo bring the evolutionary process alive and offer a more gripping and illuminating picture of evolution than has typically been taught and discussed. And fourth, for anyone who may ponder the question Where did I come from?, this book is also about our history, both the journey we have all made from egg to adult, and the long trek from the origin of animals to the very recent origin of our species.

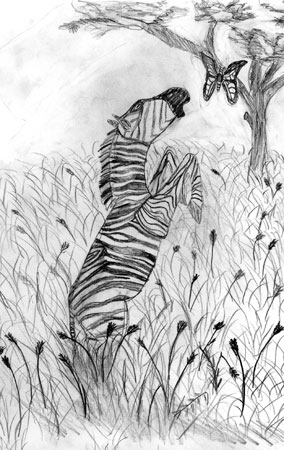

Drawing by Christopher Herr, age ten (Eagle School, Madison, Wisconsin)

Endless Forms Most Beautiful

Introduction

Butterflies,

Zebras, and

Embryos

Well shes walking through the clouds

With a circus mind thats running round Butterflies and zebras

And moonbeams and fairy tales,

Thats all she ever thinks about.

Jimi Hendrix,

Little Wing (1967)

O N A RECENT VISIT to my kids elementary school, I was enjoying the student art that decorated the hallways. Among the landscapes and portraits were many depictions of animals. I couldnt help noting that of the thousands of species to choose from, the most frequently drawn mammal was the zebra. And the most represented animal of any kind was the butterfly. We live in Wisconsin and, this being the middle of winter, the kids were not drawing what they saw out the window. So, why all the butterflies and zebras?

I am certain that these pieces of art reflect the childrens deep connection to animal formstheir shapes, patterns, and colors. We all feel that connection. Thats why we visit zoos to see exotic animals, flock to the new phenomenon of butterfly aviaries, go to aquaria, and spend billions on our animal companionsdogs, cats, birds, and even fish. We most often choose our favorite breeds and species on aesthetic grounds. Yet, we are also mesmerized, and sometimes terrified, by the more extreme animal forms: giant squids, carnivorous dinosaurs, or bird-eating spiders.

The same attraction to and fascination with animal forms has motivated the greatest naturalists for centuries. In cold, gray, damp pre-Victorian England, young Charles Darwin read Alexander von Humboldts Personal Narrative , a 2000-page account of his voyage to and around South America. Darwin was so consumed that he later claimed that all he thought, spoke, or dreamt about were schemes to get to see the sights of the Tropics that Humboldt described. He leaped at the chance when the opportunity to sail on the Beagle arose in 1831. Darwin later wrote to Humboldt, My whole course of life is due to having read and re-read as a youth, this personal narrative. Two other Englishmen, Henry Walter Bates, a twenty-two-year-old office clerk and avid bug collector, and his self-taught naturalist friend, Alfred Russel Wallace, also dreamt of travel abroad to collect new species. Upon reading an Americans account of a journey to Brazil, Bates and Wallace immediately decided to head there (in 1848). Darwins voyage lasted five years, Bates remained in the Tropics for eleven years, and Wallace spent fourteen years over the course of two journeys. These dreamers would, based upon the thousands of species that they saw and collected, launch the first revolution in biology.