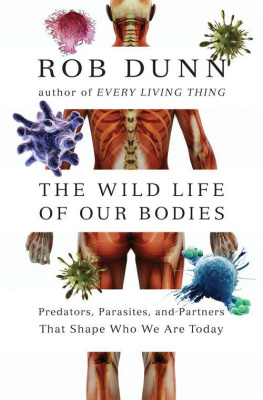

The Wild Life of Our Bodies

Predators, Parasites, and

Partners That Shape Who

We Are Today

Rob Dunn

for Monica, my favorite wild life

Contents

S ome night,when the moon sneaks through your curtains and finds you still awake in bed,look beside you at your companion. (If you are alone, look at yourself.) Look atthe fingernails, smooth beside the rougher skin, not unlike claws. Look at thehands, full of bones strung together by strings of tendons. Follow the bonesjust below the skin of the arm to the elbow and up along the beautiful shoulderto the neck that, at this moment, might seem to be the loveliest thing you haveever encountered. This body, composed of flesh and desires, evolved in the treesin Africa and Asia, where those nails helped cling to a branch to keep fromfalling to predators on the ground. You find yourself at this moment beside ananimal that was, very recently, wild.

Some days we remember and feel our connection towhat came before us. As we watch a chimpanzee on TV and see its gestures,kindnesses, and cruelties, we feel empathy. As we pick up a turtle in the road,we notice its legs, strange eyes, and a body not so unlike ours. We feel itmoving in our hands like some deep muscle of life. But most days we are lessaware of being part of a broader community of living species. We no longer seeourselves as part of nature.

Yet our history clings to us, whether we notice ornot. In the last several years, dozens of new and separate discoveries byresearchers in anthropology, medicine, neurobiology, architecture, andecologyespecially ecologyhave made that much clear. The more we distanceourselves from our evolutionary history, the more we seem to feel the pull ofuncut strings of our heritage. There are metaphorical or even spiritual ways inwhich we might ache for the past, but I mean something much more physical. Imean the ache that our bodies feel in being removed from the ecological contextin which they existed for millennia. In being separated from the web of lifewith which we evolved, we are feeling effects, some good, others bad, but nearlyall consequential, not just for how but even who we are.

We take our modern rituals of work and leisure forgranted, and yet for nearly every bit of our history we lived outside, naked ornearly so. We sat, when we dared, on branches. We slept in nests made of sticks,mud, and smooth leaves. We roamed and foraged and knew about the landscape thatwas around us because we had to, because from its colorful fruits and treasureswe ate and either lived or did not. In our transition to modern life, one canmake long lists of the things our bodies might miss. It was not long ago that westill walked on four legs. Our bodies remain awkward standing straight. We runfast, but not so fast, and we do it by leaning forward toward that older gait.Our backs, as we sit all day, every day, pain us with our four-footed history.And as the eminent scientist Paul Ehrlich, author of ThePopulation Bomb , put it, standing up also made it harder for us tosniff each other. So much for the good old days.

Biologists and philosophers have pondered forgenerations the ways in which our modern lives may be disconnected from ourpasts, out of synch. We are haunted by this dissonance, as many haveacknowledged, but what seems to have been relatively missed is the origin of theghosts. They arise from changes in the species with which we interact. When youlook beside you in bed, you notice no more than one animal (alternativelifestyles and cats notwithstanding). For nearly all of our history, our bedsand lives were shared by multitudes. Live in a mud-walled hut in the Amazon, andbats will sleep above you, spiders beside you, the dog and cat not far away, andthen there are the insects beating themselves stupid against the dwindlinganimal-fat flame. Somewhere near you, perhaps hanging in the palm roof, would bethe drying herbs of medicine, a cooked and salted monkey hanging on a stick, andwhatever else is necessary, all gathered or killed, all local, all touched andheld and known by name. In addition, your gut would be filled with intestinalworms, your body covered in multitudes of unnamed microbes, and your lungsoccupied by a fungus uniquely your own. Beyond the edge of the village, past thedarkness between houses, would be an even wilder nature filled with insectsflexing and scraping their parts together in song, trees falling to the ground,bats fighting among the fruit, and then, of course, the predators who walksilently along our paths, waiting to pounce.

So it is that the biggest difference between ourmodern human lives and the way we used to live is not the difference of housingstyles and convenience (the transition from outhouse to penthouse). It isinstead the change in our web of ecological connections. We have gone from livesimmersed in nature to lives in which nature appears to have disappeared. Ourdisconnection from the nature in which we evolved is unprecedented in its extentand in its consequences.

We may love our new way of living, the brightlights and clean counters, the delicious food and the air-conditioningat leastour conscious brains may. Meanwhile, our bodies continue to act as though theyexpect to meet our old companions, the species with which they tangled,generation upon generation, for tens of millions of years. Some of the ways wehave distanced ourselves from other species are good; I do not miss smallpox.Other changes are neutral. They affect who we are, but not necessarily for thebetter or the worse. Many changes, though, are clearly bad. In recent years, forexample, a new suite of diseases has begun to plague us. Sickle cell anemia;diabetes; autism; allergies; many anxiety disorders; autoimmune diseases;preeclampsia; tooth, jaw, and vision problems; and even heart disease are allbecoming more common. More and more, these modern problems seem to be theconsequence of changes not in levels of pollution, globalization, or even healthcare systems, but instead of changes in the species we interact with. It is notthat we have lost particular species as much as that we have tried to removewhole kinds of lifeparasites, bacteria, wild nuts and fruits, and predators, toname a few. The loss of intestinal worms seems to be making many of our bodiesill, just as the circuits in our brains that evolved to deal with predators arenow causing us to lose our minds. Our conscious brains have led us to clean ourlives of the rest of nature, but the rest of our body, from our guts to ourimmune system, is having second thoughts.

The researchers studying different aspects of ourdisconnection from nature are in different fields. They do not tend to talk toone another, yet they have come to parallel conclusions about the extent of theconsequences of our disconnection. An immunologist holds up our intestines andsees the consequences of having removed our worms. An evolutionary biologistlooks at the appendix and notices what it had been doing in our bodies all alongwithout being noticed. A primatologist looks at the neurons in our brain andsees the vestiges of predators. Psychologists look at our fears of strangers andour wars and see in them a mark, a kind of stigma, of changes in our exposure todisease. Each thinks they have discovered something important. They havehere Iattempt to bring these stories together, weaving through them the common realitythat our past haunts us. As I do, I try to step back to reveal the elephant inthe room, or rather the effects of having removed the elephant from the room,along with worms, microbes, birds, fruit, and the rest of the most readilyapparent life.

We all know about the biodiversity crisis, but therelated crises resulting from changes in the kind of nature we interact with issimilarly immediate. Whether lying in bed or sitting in front of your computer,when you ache, you ache with the history of your origin. You ache with thecontext you miss. The savannas and forests of our ancestry are still with you.They come to you, like the pain of a missing limb, when you sneeze, when yourback aches, or when you are scared. They even come to you each time you choosewhat to plant, eat, or buy. This history comes to some more than others, but inone way or another, it comes to us all.

Next page