CONTENTS

CHAPTER 10

APPENDICES

Appendix to Chapter 15:

For Andrew

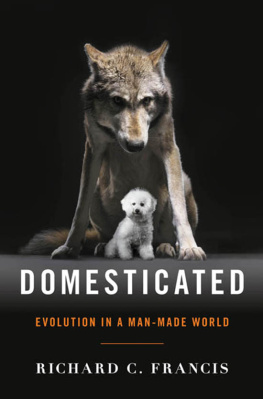

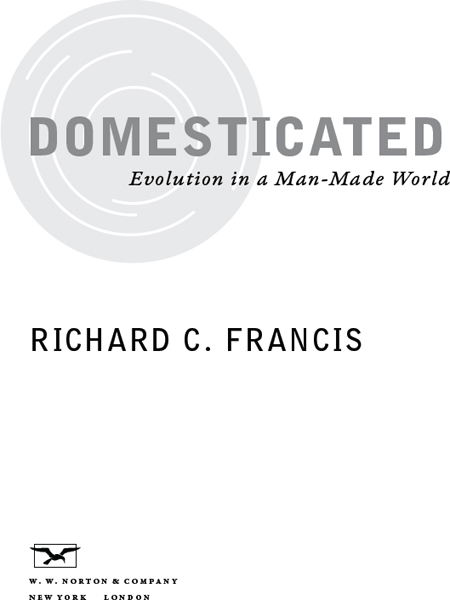

DOMESTICATED

WITHOUT OUR DOMESTICATED ANIMALS AND PLANTS, human civilization as we know it would not exist. We would still be living at a subsistence level as hunter-gatherers. It was the unprecedented surplus calories resulting from domestication that ushered in the so-called Neolithic revolution, which created the conditions for not only an agricultural economy but also urban life and, ultimately, the suite of innovations we think of as modern culture. The cradle of civilization is, not coincidentally, also the place where barley, wheat, sheep, goats, pigs, cattle, and cats commenced a fatefully intimate association with humans.

At the onset of the Neolithic revolution, an estimated 10 million humans inhabited the earth; now there are over 7 billion of us. The human population explosion has been bad for most other living things, but not for those lucky enough to warrant domestication. They have thrived quite as much as we have. Since the Neolithic, extinction rates have been 1001,000 times those of the previous 60 million years. Among those lost were the wild ancestors of domesticated species, such as the tarpan (horse) and auroch (cattle), but no domesticated species has ever become extinct. The wild ancestors of camels, cats, sheep, and goats are teetering on the brink of oblivion; their domesticated descendants, though, are among the most common large mammals on earth. In an evolutionary sense, it pays to be domesticated.

The success of domesticates comes at a price, however, in the form of increasing evolutionary submission. We humans have largely wrested from nature control of their evolutionary fate, which, it turns out, renders domesticated creatures uniquely informative for those seeking to understand the evolutionary process. Indeed, domesticated creatures provide some of the most dramatic examples of evolution in the world today. Even a creationist recognizes, at some level, that the transition from wolf to dog is an evolutionary process. That is why the artificial selection for particular traits in domesticated breedsfrom dogs to pigeonsfigured so prominently in Darwins argument for an analogous process that he called natural selection.

The fact that wolves, which competed with and even preyed on Paleolithic humans, were the first animals domesticated is testimony to the power of humans as both a conscious and unconscious evolutionary force. And throughout most of the domestication process for dogs and other mammals, the role of humans as an unconscious evolutionary force was paramount. For that reason, the distinction between natural selection and artificial selection is actually quite blurry. As we will see, the domestication process was often initiated by the domesticated animals themselves, when they sought, for various reasons, human proximity. This process of self-taming occurred primarily through ordinary natural selection. The sort of conscious selection we call artificial selection came only much later in the domestication process. There is a large gray area of transition between natural selection and artificial selection, in which humans became an increasingly important but only partly conscious component of the selection regime.

The combination of natural and artificial selection has proved very powerful indeed. The size range of domestic dogsfrom Chihuahuas to Great Danesfar exceeds not only that of wild wolves but that of the entire canine family (wolves, coyotes, jackals, foxes, etc.), both living and extinct, which originated in the Oligocene epoch nearly 40 million years ago. In a mere 15,00030,000 years the selection imposed on dogs by their association with humans has caused evolutionary alterations never experienced in the canine family during the previous 40 million years.

Evolutionary modifications of dogs by humans extend to many other traits as well, including coat color and skeletal modifications. Skull shape variation in domestic dogs exceeds not only that of all other canines combined but also that of all other carnivoresthe taxonomic group of families that includes canines, cats, bears, weasels, raccoons, hyenas, civets, seals, and sea lionscombined.

The effects of human selection on dog behavior have been no less dramatic. Most notably, domestic dogs have an evolved capacity to read human intentions. For example, they can interpret human gestures, such as pointing, to locate distant food items. Wild wolves cannot do this. In fact, dogs are much better at reading human intentions than are our closest relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas. So in some ways, the social cognition of dogs more closely resembles that of humans than does that of the great apes.

The human influence on the evolution of other domesticated creatures is only slightly less impressive. The placid hyper-uddered Holstein cow does not much resemble its wild ancestor, the noble and fierce auroch, nor do Merino sheep much resemble the mouflon, their wild ancestor, though in both cases the domesticated and wild forms share a common ancestor only 10,000 years ago. Thats a lot of evolution in a very short period of time.

Since domestication is an accelerated form of evolution, it is an ideal subject by which to nurture the intuitions and hence the understanding of nonbiologists as to how evolution works. Evolution is a historical process, but most evolution involves timescales that are hard for the uninitiated to digest, much less intuit, given the limitations of the human mind. Domestication, however, occurs over more comprehensible timescales. Dog breeds such as the English bulldog, for example, have evolved extensively in just the last 100 years. It is therefore possible to connect human history, prehistory (500030,000 BP), and evolutionary history in a more or less seamless way. This is sometimes referred to as big history, though I prefer deep history. This big or deep historical dimension provides the backdrop for the main themes that will concern me throughout.

The predomestication historythe deepest part of the deep historyis, of course, the province of evolutionary biology, specifically the branch of evolutionary biology concerned with reconstructing the genealogical relationships on the tree of life, which is called phylogenetics. Much of what we know about the period connecting predomestication history and written history comes from the burgeoning field of zooarchaeology, which combines expertise in ancient human cultures, animal biology, and natural history. The more recent history of domestication, for which we have written records, concerns the phase during which humans have assumed the most conscious control. This phase, which is still ongoing, is one of unprecedented change, for good and ill.

While this historical backdrop is, I hope, interesting in and of itself, it is also essential if we are to understand how evolution works. Domesticated creatures are familiar to one and all. As such, their transformations are easier to perceive and appreciatea prerequisite for my main aim here, which is to consider some recent and current developments in evolutionary biology through the lens of domestication.

We can consider each case of domestication as a sort of natural experiment in evolution. By natural experiment, I mean a case that is ideally suited for the study of evolution but was not planned as such. We also have natural experiments in reverse domestication, called feralization. The dingo is one such experiment. Transported to Australia approximately 5,000 years ago by proto-Polynesians, dingoes transformed from pets into the apex predator of the outback. In the process, they evolved into more wolflike creatures; indeed, dingoes provide interesting contrasts to both wolves and domestic dogs.

Next page