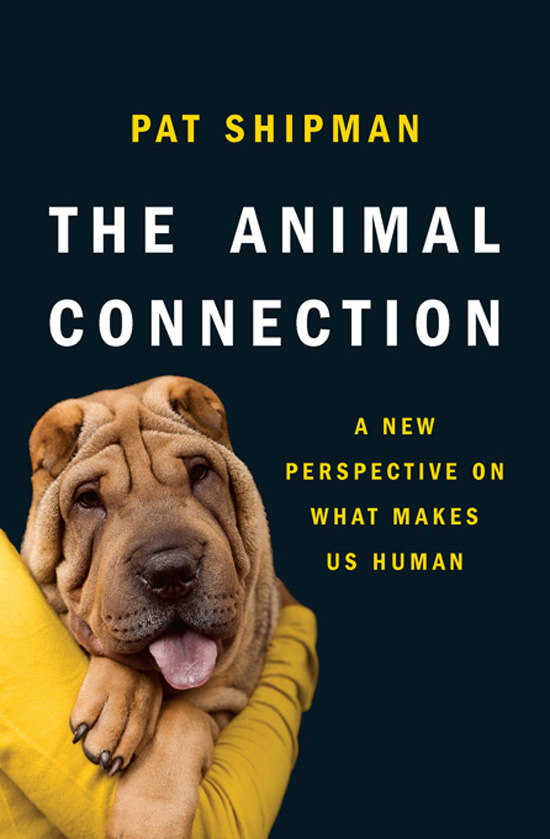

The

Animal

Connection

A New Perspective on

What Makes Us Human

Pat Shipman

W. W. Norton & Co mpany

New York London

Copyright 2011 by Pat Shipman

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Manufacturing by Courier Westford

Book design by Helene Berinsky

Production manager: Devon Zahn

Ebook conversion by Erin Campbell, TIPS Technical Publishing, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shipman, Pat, 1949

The animal connection : a new perspective on what

makes us human / Pat Shipman. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-07054-5 (hardcover)

1. Human evolution. 2. Human-animal relationships.

3. Domestication. 4. Prehistoric peoples. I. Title.

GN281.S453 2011

304.2 ' 7dc22

2010054062

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

1234567890

To all of the animals who make life worth living

Contents

Prologue

Once you find something, how do you know if its human? the woman in the back of the auditorium asked.

Questions like this come up fairly often when you are a paleoanthropologist, as I am, and give public lectures, which I do. When I get questions from nonspecialists, I try to listen with my teachers ear, the one that hears not what the questioner literally said but what the questioner meant . This particular question usually means, If you find the fossil of a higher primate, how do you tell if its an ape or a human? The question is particularly pointed because many people know that humans and chimps have more than 99 percent of their genetic codes in common.

One answer is: You know, fossils dont come with labels on them. You have to do as much or more work to figure out what adaptations a fossil species had as you did to find the fossil in the first place. You compare the anatomical features in the fossil with those of apes, of humans, and of other fossils to see which is the best match, which is the closest resemblance. And you hope you are going to find more fossils from the same species, so youll have more bones to work with.

Something in the womans voice or her intelligent eyes suggested she meant something more universal, something bigger. I believed she was asking a very profound question indeed: What does it mean to be human?

Perhaps surprisingly, the answer is not: To be like us. When you take the long perspective, Homo sapiens sapiens of today is a highly evolved member of a species that has been around and changing for hundreds of thousands of years. It may seem paradoxical, but we were not us from the very beginning of our species.

If you take both a long and broad perspective, humans are creatures that belonged to the same genus we do, Homo, and they have been around for millions of years. During that time, our ancient relatives evolved from themsomething not usinto us. But it didnt happen right away or fast.

As I started to give my questioner a detailed answer that spelled out the unique anatomical and behavioral attributes of humansteeth like this, relatively big brains, bipedal upright posture, complex tools, and fully developed language something flashed through my head, unbidden. It was a sort of cinematic collage of people of the world I had seen or read about. There were noisy, vibrant city dwellers in Prague, Accra, or Beijing and silent, black-haired Amazonian hunter-gatherers following narrow trails in the jungle. There were the elegant, proud, pastoralists of arid Kenya, like the Masai in whose territory I had excavated, and solidly built, pale-skinned, down-to-earth farmers in the American Midwest. There were tall, tanned California girls and sari-clad beauties with dark eyes and hair from Delhi, contrasting with the neatly built Efe Pygmies in the dense forests of central Africa. I thought of tribal Papua New Guineans with their lush gardens, muscular Polynesians rowing their slender, efficient boats, the very dark-skinned aboriginal cowboys of Australia, and slender Javanese with their rice paddies and beloved water buffalo. Add to that turbaned Tuaregs in the Sahara, Mongolian horse peoples on the steppes, and the Inuit hunters of Alaska, clad in bulky skin parkas and leggings against the frigid cold... Images spun through my mind.

As I watched this mental world tour, I marveled at the diversity of human lifestyles, dwellings, body builds, coloring, habits, and habitats. I also saw, for the first time, something else that unites humankind, a behavior to which few other anthropologists or biologists have paid attention.

Included in every one of those images of human beings that flashed through my head were animals. Everywhere you go, if you find people, you find animals. I hadnt realized that before. Animals may be casual or even unwanted visitors to human habitations, treasured pets, precious livestock, pursued prey, or animate transport for people and goods alike, but they are there. We adopt them, feed them, nurture them, play with them, breed them, train them, use them, and eat them. We think with animals.

I dont know why I was surprised. I have always lived with animals myselfmostly cats and horsesand feel life is incomplete without them. Living with, communicating with, and working with animals is a great joy to me.

In that moment, I realized that living with animals is a uniquely human trait. In the wild, no other mammal lives intimately with another species. No zebras adopt antelopes, no deer looks after a baby wolf in hopes of training it to protect the herd, no monkeys bring back little mongooses to feed and pet. Except in conditions of captivity, no other animal species regularly initiates long-term nurturing relationships with individuals of another species. Tick birds feed on the parasites lodged in rhino skin and rhinos tolerate their presence, but there is no evidence that one tick bird belongs to a particular rhino, or vice versa. The relationship is generalized and happenstance, not one-on-one.

Behavioral universals are very hard to come by in anthropology because human behavior is so culturally conditioned and so variable. But living with animals is indeed a human characteristic and it is both very old and profoundly important. When anthropologists field questions about what makes humans human, they do not say Our connection to animals, but I think they should.

The serious question that woman asked suddenly showed me that probably the longest and most enduring trend in human evolution has been a gradual intensification of our involvement with animals. The connection between humans and animals has in large measure defined who and what we are as a species. And, I would speculate, this connection with animals has been selected for genetically.

As I thought through the story of human evolution with this insight in mind, I realized I had misinterpreted a number of facts and milestones in human evolution. What was now clear to me was that the connection between animals and humans runs through the last 2.6 million years of our evolution like a fast-moving river, carrying our behavior and abilities into modern humanness. It was the animal connection that brought together apparently disparate developments of human evolution into one continuous theme.

Next page