The project Roads to MidgardOld Norse Religion in Long-term Perspectives was financed by the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation. Financial support has also been provided by Lund University, Malm Heritage, and the Swedish Research Council.

Preface

My study of animals, or rather my study of the relations between humans and animals, is a part of the larger project Roads to Midgard: Old Norse Religion in Long-term Perspectives. This is a multidisciplinary project at Lund University, Sweden, involving archaeology, medieval archaeology, and history of religion. As one of the archaeologists in the project, I have carried out a long-term study of ritual practice in Old Norse religion, and how rituals can be related to Old Norse mythology.

The interdisciplinary character of the Midgard Project (as it is called for short), and the contrast between archaeological material culture and written texts, has yielded far-reaching research findings. Words and concepts, outlooks and research perspectives from different disciplines came together during the project period, chiefly in the intensive years 19992004. One result of the interdisciplinary discussions within the project was that my own sense of belonging to the subject of archaeology was strengthened. The temporal depth of archaeology and the focus on oral cultures exerted an increasing fascination on me. The prehistoric periods in Scandinavia are a time with little or no textual sources. They were oral cultures where material culture was important for social identity, for communicating and remembering. It is the fragmentary material remnants that are in focus in this book, where the intention, besides studying animals, is to sum up the potential of archaeology to study religion.

There are several interpretative barriers to researching attitudes to animals, not least because of anthropocentrism. Yet it is a challenge to study the Norse pre-Christian conceptual world and with it an extinct religion. This book chiefly concerns how a pre-Christian everyday mentality shaped the keeping of animals and the outlook on animals, and how the different animals seem to have had functional, symbolic, and connotative meanings. The source material of prehistoric archaeology is viewed in relation to the medieval texts that were written down long after the period they concern. The subtitle of the book stressesthe scientific study of mentality, ritual, power, and lifestyle based on archaeological material culture and textual evidence.

Animals and Humans: Recurrent symbiosis in archaeology and Old Norse religion has grown over a long time. I have gradually changed the way I think archaeologically. Several passages and discussions from my earlier articles written in the course of the project have been incorporated, but they have also been reappraised during the work with this book (Jennbert 2000, 2002, 2003a, b, 2004a, b, 2005, 2006a, b).

The research was mainly done in the years 19992005 as part of my research lectureship in the archaeology of religion at Lund University, and subsequently parallel to my work as head of the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Lund University.

All the participants in the Midgard Project have been significant, so I would like to take the opportunity to thank them all for the wonderful years spent together on the project: Anders Andrn, Catharina Raudvere, Stefan Arvidsson, sa Berggren, Ann-Britt Falk, Peter Habbe, Ann-Mari Hllans, Maria Lundberg Domeij, Ann-Lili Nielsen, Gunnar Nordanskog, Erik Magntorn, Nina Nordstrm, Heike Peter, Gun-Britt Rudin, Jrn Staecker, and Louise Strbeck. Thanks to Alan Crozier, who translated the text into English, and to Annika Olsson, editor at Nordic Academic Press, for fruitful collaboration. Thanks also to Gunnar Broberg and Inger Ahlstedt Yrlid, Deans of the Faculty of History and Philosophy at Lund University, who many years ago put their faith in my project about animals in the archaeology of religion. The book is dedicated to my family: Anders, Karin, and Maria.

Lund 2011

Kristina Jennbert

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

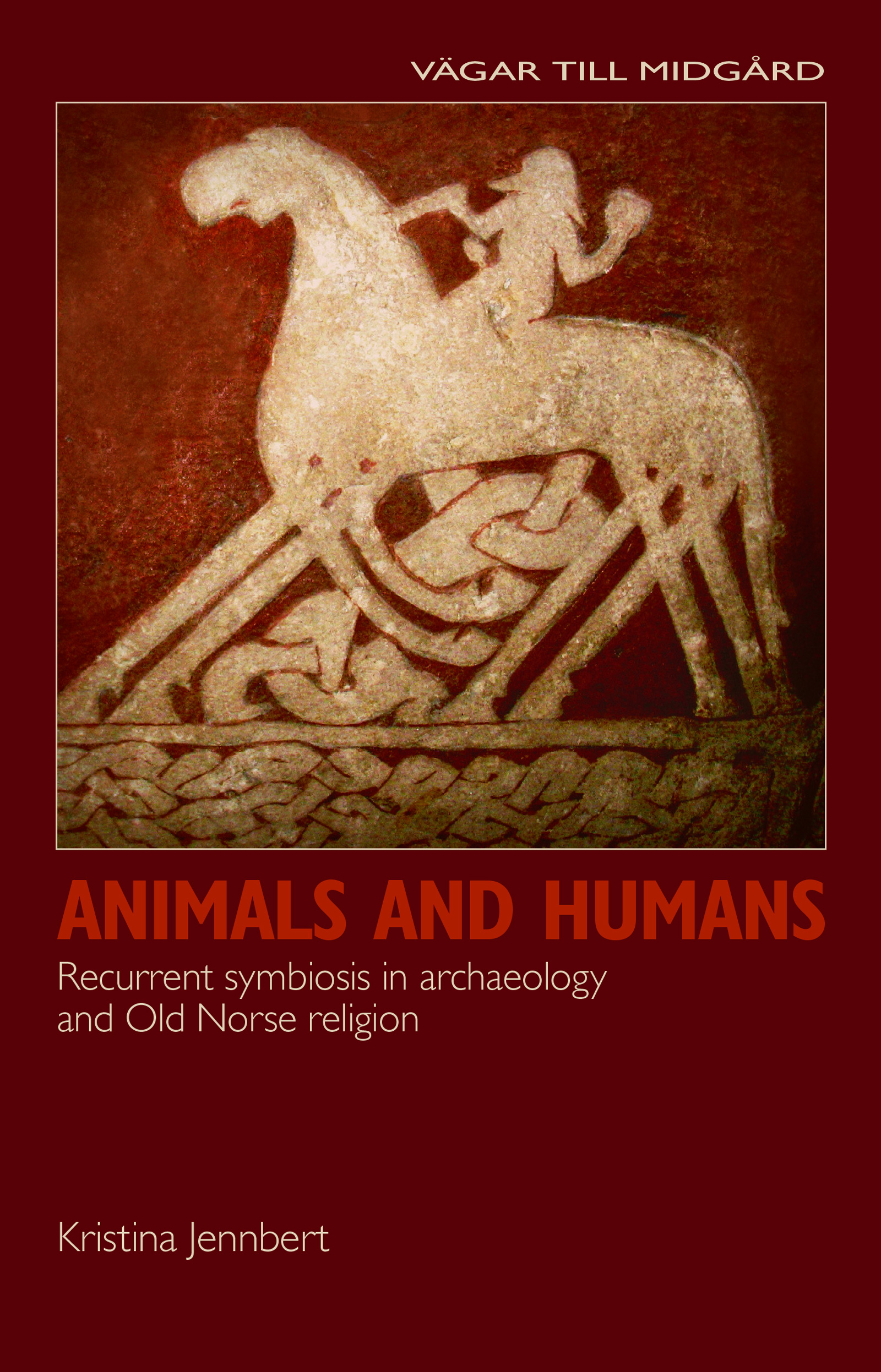

Animals are a fascinating object of study, whether you are standing in front of one of the famous Palaeolithic cave paintings of Lascaux in the Dordogne, or looking at Viking Age artefacts with pictures of animals and fantasy creatures. In the cave at Lascaux the animals step out of the rock; they are in the rock itself and the visitor almost becomes a part of the rock. On the Viking Age objects the real and imaginary animals mock the observer, grasping, intertwining, and grimacing. In Norse mythology, Odins eight-legged horse Sleipnir communicates speed and strength. He was conceived by Loki, who had turned himself into a mare to distract the stallion Svadilfari so that the giant who was supposed to build Asgard was delayed in his work. Sleipnir has the ability to move through the world of the gods (see the cover picture). Why is this? What does Sleipnir actually represent? Animals do not leave the observer unmoved; animals concern us.

Animals play an important part for humans. We relate to animals in different ways and are somehow dependent on animals for their practical utility as a source of food, for transport, for medical research, and as company. Besides the functional aspects, animals and their properties hold symbolic values for humans. Through their mere existence, animals contribute to the way people regard themselves.