First published in 2000 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Brian Morris 2000

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by JS Typesetting, Wellingborough, Northants.

ISBN 13: 978-1-859-73486-5 (hbk)

I first came to Malawi in February 1958, sitting with my rucksack on the back of a pick-up truck as it passed through the Fort Manning (Mchinji) customs post. I had spent the previous four months hitch-hiking around south and central Africa, mostly sleeping rough. During that time I encountered no other hitch-hiker, and very few tarred roads, and the only place I met tourists was at the Victoria Falls. I was, however, so attracted to Malawi and its people, that I decided to give up my nomadic existence. I was fortunate to find a job working as a tea planter for Blantyre and East Africa Ltd, an old company founded by Hynde and Stark around the tum of the century. I spent over seven years as a tea planter working in the Thyolo (Zoa) and Mulanje (Limbuli) districts, spending much of my spare time engaged in natural history pursuits - my primary interests being small mammals (especially mice) and epiphytic orchids. The first article I ever published was based on my spare-time activities in Zoa, where I spent many hours with local people digging up mice. It was entitled Denizen of the Evergreen Forest (1962), and recorded the ecology and behaviour of the rather rare pouched mouse - Beamys hindei.

Since those days I have regularly returned to Malawi to undertake ethnobiological studies. I thus have a life-long interest in Malawi - in its history, in the culture of its people, and in its fauna and flora. Some of my most memorable life experiences have been in Malawi, and many of my closest and cherished friendships have been with Malawians, or with expatriates who have spent their lives in Malawi.

Altogether I have spent over ten years of my life in Malawi, and apart from Chitipa and Karonga, I have visited and spent time in every part of the country, having climbed or explored almost every hill or mountain -usually with a Malawian as a companion, and looking for birds, mammals, medicines, epiphytic orchids or fungi, whichever was my current interest.

The present study, like my earlier study The Power of Animals, is specifically based on ethno-zoological researches undertaken in 19901, which were supported with a grant from the Nuffield Foundation. For this support I am grateful.

I should also like to thank, with respect to this present study, many friends and colleagues who have given me valuable data, encouragement, support and hospitality over the past thirty years. In particular I should like to sincerely thank: Derrick Arnall, Father Claude Boucher, Wyson Bowa, Carl Bruessow and Gillian Knox, Shaya Busman, Salimu Chin-yangala, Dave and Iris Cornelius, Janet and Les Doran, Jafali Dzomba, Efe Ncherawata, Cornell Dudley, the late Cynthia and Eric Emtage, Peter and Suzie Forster, Frank and Iona Kippax, John and Anne Killick, Heronimo Luke, Useni Lifa, Kitty Kunamano and her daughters, John Kajalwiche and his sister Evenesi Muluwa, Catherine Mandelumbe, the late Ganda Makalani, Late Malemia and her family, Bob and Claire Medland, Davison Potani, Kings Phiri, Lackson Ndalama, Hassam Patel and his family, Pritam Rattan, Pat Royle, Lady Margaret Roseveare, Brian and Anne Sherry, Chenita Suleman and her family, Patrick and Poppit Rogers, Francis and Annabel Shaxson, Chijonjazi Muzimu Shumbe, Lance Tickell, Catherine and Stephen Temple, the late Samson Waiti, George and Helen Welsh, Brian and June Walker, John and Fumiyo Wilson, and the late Jessie Williamson.

I should also like to thank those who generously gave me institutional support: The Centre for Social Research, University of Malawi (Wycliffe Chilowa); The National Archives of Malawi (Frances Kachala); Matthew Matemba and many members of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife; and M.G Kumwenda and George Sembereka of The National Museums of Malawi.

Finally, I should like to thank my family and colleagues at Goldsmiths College for their continuing support and particularly to thank Emma Barry who kindly typed my manuscript.

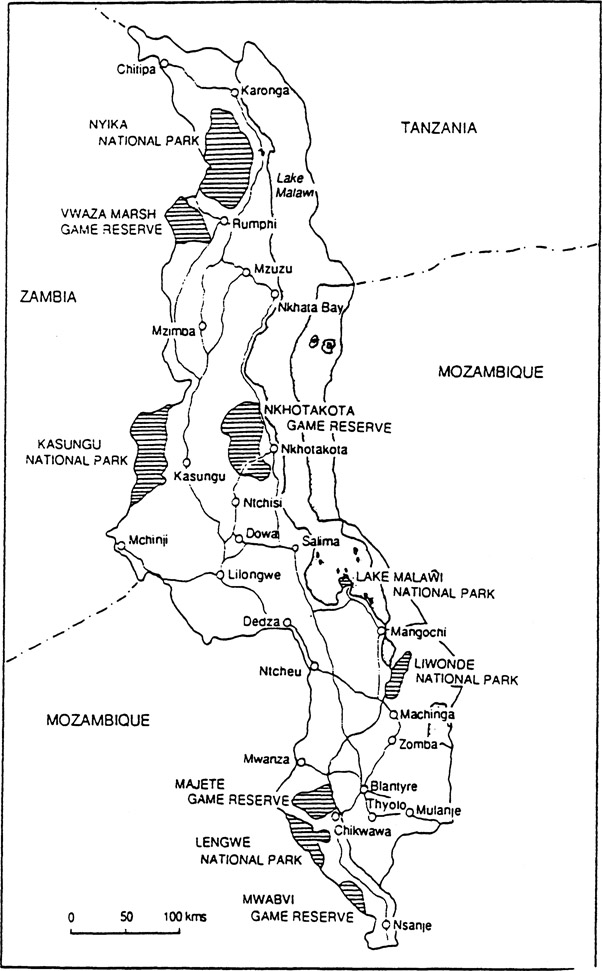

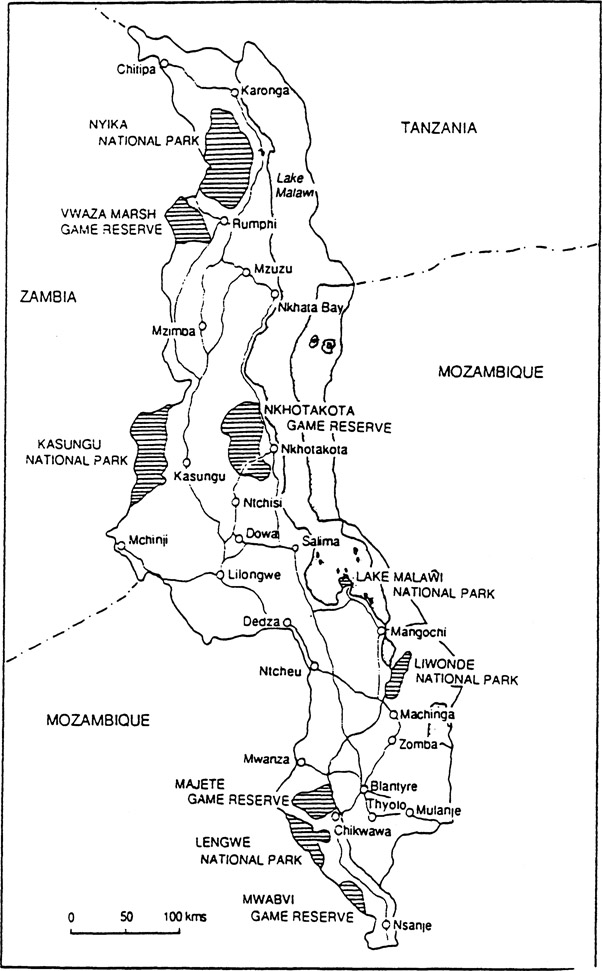

Map I Malawis Wildlife Reserve

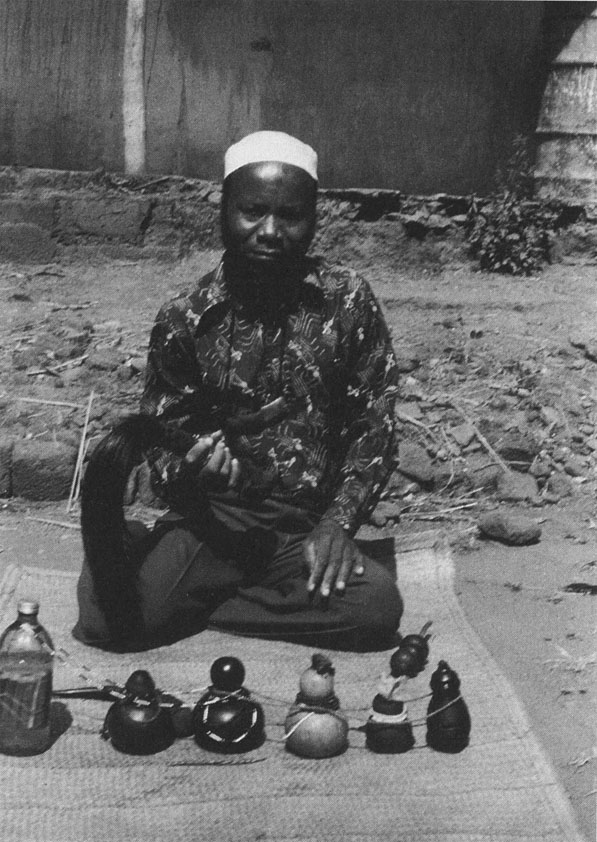

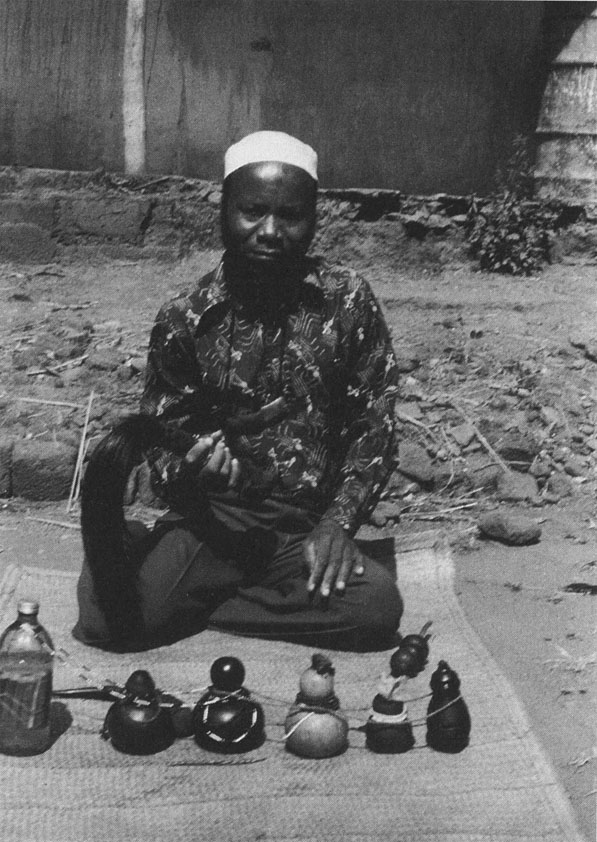

Figure 1 The late Samson Waiti, herbalist-diviner, Domasi March 1980

Prologue

This book explores the role of animals in the rituals and religious life of the matrilineal people of Malawi. It forms a sequel and a companion volume to my study The Power of Animals (1998), which focused on the historical dialectic to be found in Malawi between subsistence agriculture focused around a group of matrilineally related women, and the hunting of animals by men. In that study I describe the hunting traditions to be found in Malawi, the folk classification of animals, and the important part that animals play in oral traditions, and as food (meat) and medicine. I attempted to show the multiple ways in which Malawian people relate to animals - pragmatic, intellectual, realist, aesthetic, social and symbolic. This present study focuses on their sacramental attitude to animals, particularly the role that animals play in life cycle rituals, and the relationship of animals to the divinity and the spirits (mizimu) of the ancestors. The two books together aim to affirm the crucial importance of animals in the social and cultural life of Malawian people. It thus counters the mistaken impression that many postmodern anthropologists have, namely that animals are just not worth bothering about as they are a topic of marginal interest (as one scholar put it) to anthropologists.

This introductory chapter aims to provide some of the background material relevant to the study, and discusses the theoretical perspective that informs the study, the social setting, animal/human relationships in an historical context, and my approach to the study, concluding with an outline of its content.