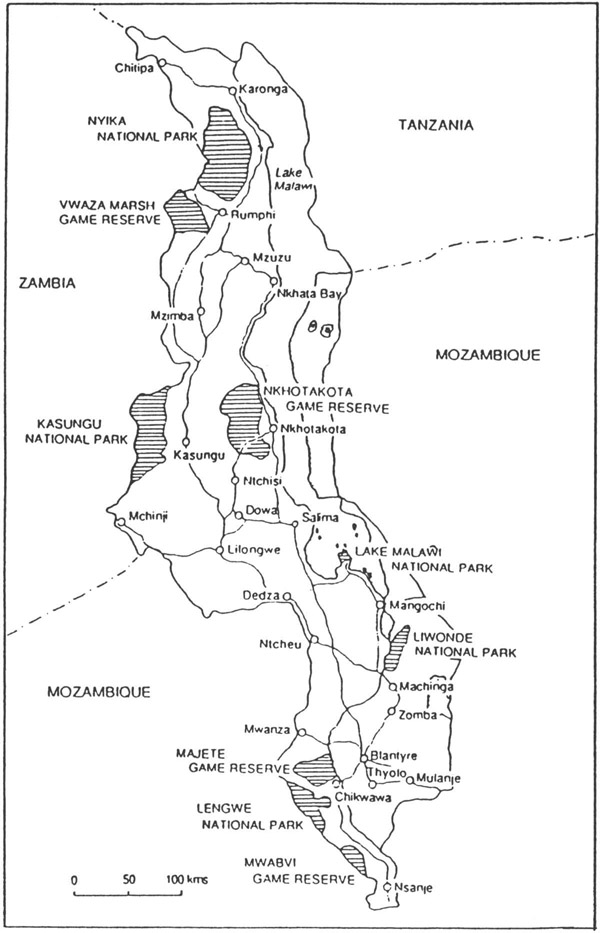

I first came to Malawi in February 1958, sitting with my rucksack on the back of a pick-up truck as it passed through the Fort Manning (Mchinji) customs post. I had spent the previous four months hitch-hiking around south and central Africa, mostly sleeping rough. During that time I encountered no other hitch-hiker and very few tarred roads, and the only place I met tourists was at the Victoria Falls. I was, however, so attracted to Malawi and its people that I decided to give up my nomadic existence. I was fortunate to find a job working as a tea planter for Blantyre and East Africa Ltd., an old company founded by Hynde and Stark around the turn of the century. I spent over seven years as a tea planter working in the Thyolo (Zoa) and Mulanje (Limbuli) districts, spending much of my spare time engaged in natural history pursuits, my primary interests being small mammals (especially mice) and epiphytic orchids. The first article I ever published was based on my spare-time activities in Zoa, where I spent many hours with local people digging up mice. It was entitled Denizen of the Evergreen Forest (1962), and recorded the ecology and behaviour of the rather rare pouched mouse (Beamys hindei).

Since those days I have regularly returned to Malawi to undertake ethnobiological studies. I thus have a lifelong interest in the country and its history, the culture of its people and its fauna and flora. Some of my most memorable life experiences have been in Malawi, and many of my closest and cherished friendships have been with Malawians or with expatriates who have spent their lives in the country. Altogether, I have spent over ten years of my life in Malawi, and apart from Chitipa and Karonga, I have visited and spent time in every part of the country, having climbed or explored almost every hill or mountain - usually with a Malawian as a companion, and looking for birds, mammals, medicines, epiphytic orchids or fungi, whichever was my current interest.

The present study is specifically based on ethnozoological researches undertaken in 19901991, which were supported with a grant from the Nuffield Foundation. For this support I am grateful.

With respect to this present study, I should also like to thank many friends and colleagues who have given me valuable data, encouragement, support and hospitality over the past thirty years, in particular, Derrick Amall, Father Claude Boucher, Wyson Bowa, Carl Bruessow and Gillian Knox, Shaya Busman, Salimu Chinyangala, Janet and Les Doran, Jafali Dzomba, Efe Ncherawata, Cornell Dudley, the late Cynthia and Eric Emtage, Peter and Suzie Forster, Jillian Hugo, Revd Peter and Vera Garland, the late Paul Kotokwa, Frank and Iona Kippax, John and Anne Killick, Heronimo Luke, Useni Ufa, Kitty Kunamano and her daughters, John Kajalwiche and his sister Evenesi Muluwa, Catherine Mandelumbe, the late Ganda Makalani, Late Malemia and her family, Bob and Claire Medland, Davison Potani, Kings Phiri, Lackson Ndalama, Hassam Patel and his family, Pritam Rattan, Pat Royle, Lady Margaret Roseveare, Brian and Anne Sherry, Chenita Suleman and her family, Patrick and Poppit Rogers, Francis and Annabel Shaxson, Chijonjazi Muzimu Shumbe, Lance Tickell, Catherine and Stephen Temple, the late Samson Waiti, George and Helen Welsh, Brian and June Walker, John and Fumiyo Wilson, and the late Jessie Williamson.

I should also like to thank those who generously gave me institutional support: the Centre for Social Research, University of Malawi (Wycliffe Chilowa); the National Archives of Malawi (Frances Kachala); Matthew Matemba and many members of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife; and M.G. Kumwenda and George Sembereka of the National Museums of Malawi.

Finally, I should like to thank my family and colleagues at Goldsmiths College for their continuing support, and particularly Pat Caplan, who helped me to structure my English, and Irene Goes, who typed my manuscript.