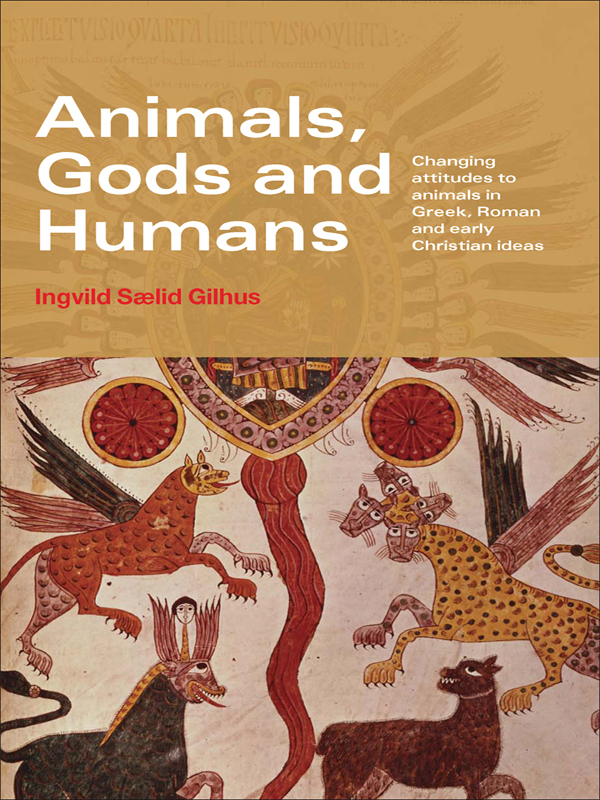

ANIMALS, GODS AND HUMANS

Ingvild Slid Gilhus explores the transition from traditional Greek and Roman religion to Christianity in the Roman Empire and the effect of this change on how animals were regarded, illustrating the main factors in the creation of a Christian conception of animals. One of the underlying assumptions of the book is that changes in the way animal motifs are used and the way humananimal relations are conceptualized serve as indicators of more general cultural shifts. Gilhus attests that in late antiquity, animals were used as symbols in a general redefinition of cultural values and assumptions.

A wide range of key texts are consulted, ranging from philosophical treatises to novels and poems on metamorphoses; from biographies of holy men such as Apollonius of Tyana and Antony, the Christian desert ascetic, to natural history; from the New Testament via Gnostic texts to the Church fathers; from pagan and Christian criticism of animal sacrifice to the acts of the martyrs. Both the pagan and the Christian conception of animals remained rich and multi-layered through the centuries, and this book presents the dominant themes and developments in the conception of animals without losing that complexity.

Ingvild Slid Gilhus is professor of the History of Religions at the University of Bergen. Her publications include Laughing Gods, Weeping Virgins (Routledge 1997).

First published 2006

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

2006 Ingvild Slid Gilhus

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN10: 0-415-38649-7 (hbk)

ISBN10: 0-415-38650-0 (pbk)

ISBN13: 978-0-415-38649-4 (hbk)

ISBN13: 978-0-415-38650-0 (pbk)

Taylor & Francis Group is the Academic Division of T&F Informa plc.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study of animals in ancient religion started as part of a cross-disciplinary research project, The construction of Christian identity in antiquity, funded by the Norwegian Research Council. By means of this project our research group established Christian antiquity as a distinct and interdisciplinary field of study in Norway. The stimulating environment created in this group has been a great inspiration for this study of animals. I am deeply indebted to those involved, especially to Halvor Moxness who was instrumental in getting the idea of a joint project on Christian antiquity to materialize.

I will like to thank all my colleagues of the interdisciplinary milieu of the Institute of Classic Philology, Russian and the History of Religions at the University of Bergen for inspiring seminaries, interesting discussions and constructiv criticism.

During the last three years the study of animals has been continued in a small research group focusing on life-processes and body in antiquity, funded by the Norwegian Research Council. I want to thank Dag istein Endsj, Hugo Lundhaug, Turid Karlsen Seim and Gunhild Vidn for critical reading, fruitful discussions and inspiration.

My thanks are also due to Siv Ellen Kraft and Richard H. Pierce for helpful comments on parts of the manuscript. My friend and colleague Lisbeth Mikaelsson has been a great support during all the ups and downs of the project. Troels Engberg-Pedersen generously offered to read the whole manuscript, I am grateful for his careful reading.

I extend my thanks to the anonymous reviewers of Routledge who provided many valuable suggestions. I further want to thank the librarians at the University Library, Bergen, especially Kari Nordmo, who have always provided me with the books I needed. I offer my sincere thanks to Marite Sapiets for improving my English.

I would like to thank Walter de Gruyter and the Swedish Institute in Rome for permission to reprint revised versions of previously published papers. contains revised portions of my article The animal sacrifice and its critics, published in Barbro Santillo Frizell (ed), PECUS. Man and Animal in Antiquity, Rome 2004, pp. 116120.

As for institutional support, I am grateful to the University of Bergen for excellent working conditions and to the Norwegian Research Council for grants.

Finally, with all my heart I thank my husband Nils Erik Gilhus for his unfaltering encouragement and never failing support.

Ingvild Slid Gilhus

July 2005

INTRODUCTION

Animals, gods and humans

Animals are beings with which we may have social relations. We feel sympathy and affection for them, but we also exploit them for our own benefit, for company, sport or nourishment. They are persons and things, friends and food. We communicate with animals, but we also kill, cook and eat them. Animals are similar to us as well as different from us, which encourages us to imagine ourselves as them to conceptualize our own being and to use them as symbols to make sense of our world.

Our thinking about animals is not simple, any more than our feelings for them are straightforward. There is a conflict between our friendliness for some animals and our fear of others, also between our economic interest in them and a natural empathy for living beings when we have the imagination to think of ourselves in their place. By arousing contradictory thoughts and a multitude of emotions, animals become natural symbols and such stuff as myths are made of.

The relationship between animals and humans is a relationship between one species and a tremendous variety of others. Even if we feel that there is an unbridgeable gap between our species and all others, this gap is viewed differently with regard to different species, which contributes to making the relationship between humans and animals extremely complex (Midgley 1988). How kinship and otherness, closeness and distance between humans and animals are experienced and expressed varies in different types of discourse, and different cultural interpretations may be made of the same animal.

In religions, animals appear as the third party in the interaction between gods and human beings, often as mediators. In this trinity, animals and humans share a flesh-and-blood reality, while gods are creatures of human imagination and tradition. This does not necessarily mean that gods are seen as less real than humans and animals usually they are thought of as more real. Rituals function above all to establish and confirm the reality of the gods. Killing animals in honour of them and offering them part of the meat from the sacrifice was one way in which their reality was established.

Historical changes and outdated answers

At some points in history, major changes occur in the religious meaning and functions of animals. This was so in India nearly three thousand years ago, when the sacrificing of animals was replaced by bloodless offerings, eating meat was deemed less pure than a vegetarian diet, and doing no injury to any living being became a universal ethical command in Brahmanical lawbooks (Jacobsen 1994). In England, attitudes to the natural world changed in the early modern period. Animals were viewed with increasing sympathy, and even writers in the Christian tradition no longer saw animals as made solely for human sustenance (Thomas 1984: 166). In late antiquity, a major change appeared, when the main religious institution, the animal sacrifice, was replaced by Christian rituals, which no longer included any offering of animal flesh. At the same time, Christians continued to employ a sacrificial terminology. They regarded the death of Christ as fulfilling the sacrificial rites of the Old Testament and used the sacrificial lamb as a symbol for Christ (Snyder 1991: 1415). With Christianity, the human body became the key symbol in a religion that focused on the death and resurrection of Christ, and the ultimate hope of believers was their own bodily resurrection.