PLATOS ANIMALS

STUDIES IN CONTINENTAL THOUGHT

John Sallis, editor

Consulting Editors

Robert Bernasconi | William L. McBride |

Rudolph Bernet | J. N. Mohanty |

John D. Caputo | Mary Rawlinson |

David Carr | Tom Rockmore |

Edward S. Casey | Calvin O. Schrag |

Hubert Dreyfus | Reiner Schrmann |

Don Ihde | Charles E. Scott |

David Farrell Krell | Thomas Sheehan |

Lenore Langsdorf | Robert Sokolowski |

Alphonso Lingis | Bruce W. Wilshire |

David Wood

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2015 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

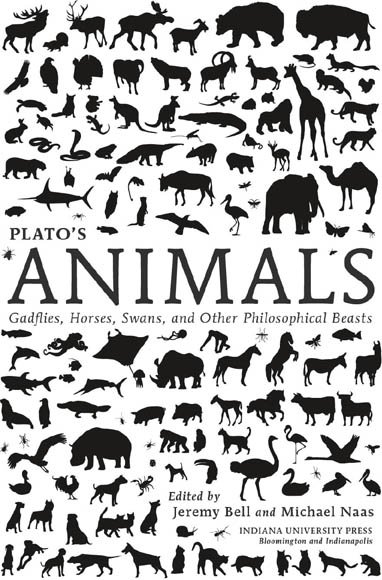

Platos animals : gadflies, horses, swans, and other philosophical beasts / Edited by Jeremy Bell and Michael Naas.

pages cm. (Studies in continental thought)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-01613-3 (hardback : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-253-01617-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01620-1 (ebook) 1. Plato. Dialogues. 2. Animals (Philosophy)

I. Bell, Jeremy, [date] editor. II. Naas, Michael, editor.

B398.A64P53 2015

184dc23

2014039533

1 2 3 4 5 20 19 18 17 16 15

Contents

PLATOS ANIMALS

Editors Introduction

Platos Menagerie

AS EVERY STUDENT of philosophy well knows, Socrates was truly a beast, a philosophical animal par excellence. In the Apology, he compares himself to a gadfly who has spent his entire life stinging the lethargic horse that is the city of Athens in order to keep it from falling into slumbering ignorance. In the Meno, Socrates is portrayed as a stingray or, more accurately, a torpedo ray who shocks or benumbs his interlocutors and causes them to question all their previously held beliefs, while in the Symposium he is compared to a venomous snake whose philosophical discourses strike at the heart or soul of those who hear them. In other dialogues, Socrates compares himself not to some stinging or biting beast, some predatory animal, but precisely the opposite, to a fawn at the mercy of a lion in the Charmides or, in Alcibiades I, to an old stork who hopes to be cared for by his young, that is, by his students. And then there is the Phaedo, the dialogue that takes place on the day of his execution, where Socrates compares himself to a prophetic swan singing his most beautiful songarguments about the immortality of the soulin anticipation of his imminent death.

Gadfly and horse, swan, snake, stork, fawn, and torpedo ray: this is already a pretty impressive and diverse assembly of animals. But it is really just the beginning of the enormous bestiary contained in Platos dialogues. Indeed, animal images, examples, analogies, myths, or fables are used in almost every one of Platos dialogues to help characterize, delimit, and define many of the dialogues most important figures and themes. They are used to portray not just Socrates but many other characters in the dialogues, from the wolfish Thrasymachus of the Republic to the venerable racehorse Parmenides of the Parmenides. Even more, animals are used throughout the dialogues to develop some of Platos most important political or philosophical ideas. In the Republic, for example, the guardians of the ideal polis are compared to trained guard dogs who must protect the state from marauding wolves, that is, from tyrants and sophists of various kinds. In the same dialogue, the human soul is itself compared to a composite animal with a human head, a lions torso, and nether parts like a multiheaded beast, while in the Phaedrus it is likened to a charioteer and two horses, with the former ruling over and guiding the latter.

It is thus often through images or examples of animals, along with the analogical relationships that come along with these, that Plato is able to develop a hierarchy not just between humans and animals but between rulers and the ruled, men and women, adults and children, free men and slaves, and so on. It is not too much to say that animal references are employed to help characterize, explain, or value almost every aspect of human life. In the Republic and the Phaedo, we even hear Socrates argue that the character and destiny of animals pursue humans beyond life right into the afterlife, since it is suggested there that a human soul that does not devote itself to a life of philosophy is likely upon its death to pass into the body of a donkey, hawk, kite, or wolf, or, if it is lucky, a bee, wasp, or ant.

Platos dialogues are thus teeming with animals of every kind, not only gadflies, horses, swans, snakes, and torpedo rays, but wolves, dogs, pigs, donkeys, hawks, bees, roosters, bulls, foxes, monkeys, locusts, oystersand the list goes on. By our reckoning, there is but a single dialogue (the Crito) that does not contain any obvious reference to animals, while most dialogues have many. What is more, throughout Platos dialogues the activity or enterprise of philosophy itself is often compared to a hunt, where the interlocutors are the hunters and the object of the dialogues searchideas of justice, beauty, courage, piety, or friendshiptheir elusive animal prey. Hence animal images, examples, metaphors, and tropes are used throughout the dialogues to develop not just Platos dialogical characters, and not just the differences between the human and the animal, but many of the most important aspects of his ontology, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics, and political theory. To understand Platos dialogues, then, it seems necessary to explain the presence of all these animals in the dialogues, their strategic or rhetorical necessity as well as their philosophical significance.

Platos Animals is an attempt to give an account of the scope and importance of this remarkable bestiary in Platos philosophy. It is a first attempt not just to gather or collect the many animal references into a single volume but to explain their function or purpose in the dialogues. While there have been numerous books in recent years that have treated the question of the animal in contemporary thought, or else the presence and significance of animals in a particular thinker, for example in Nietzsche, there has been nothing of the sort on Platowhose bestiary is, we believe, just as rich and important for understanding his work as Nietzsches bestiary is for his.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.