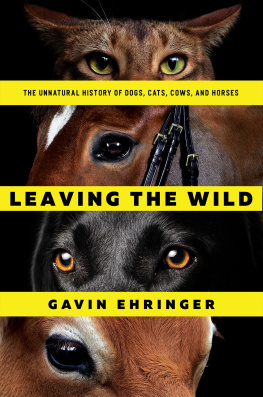

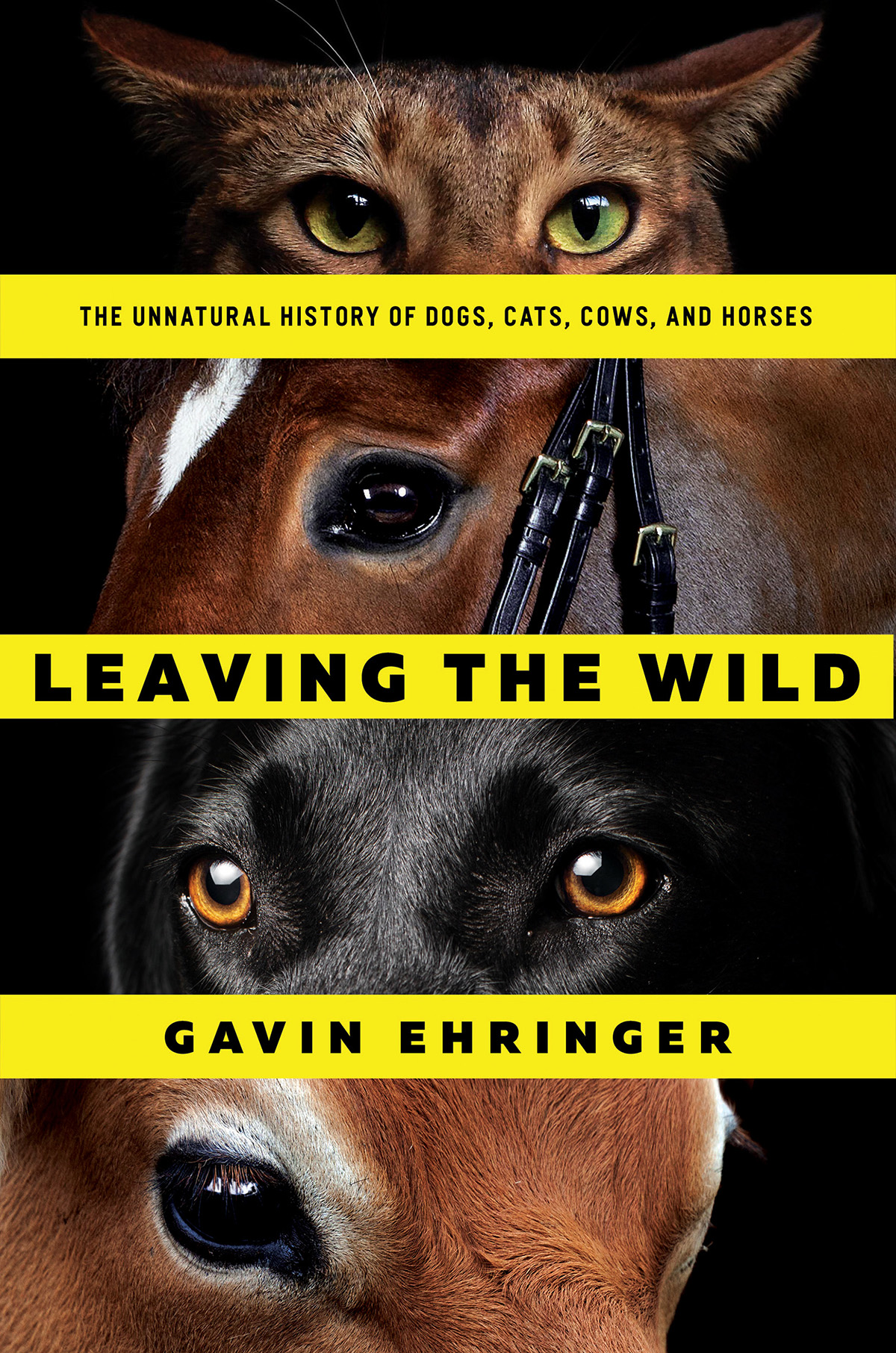

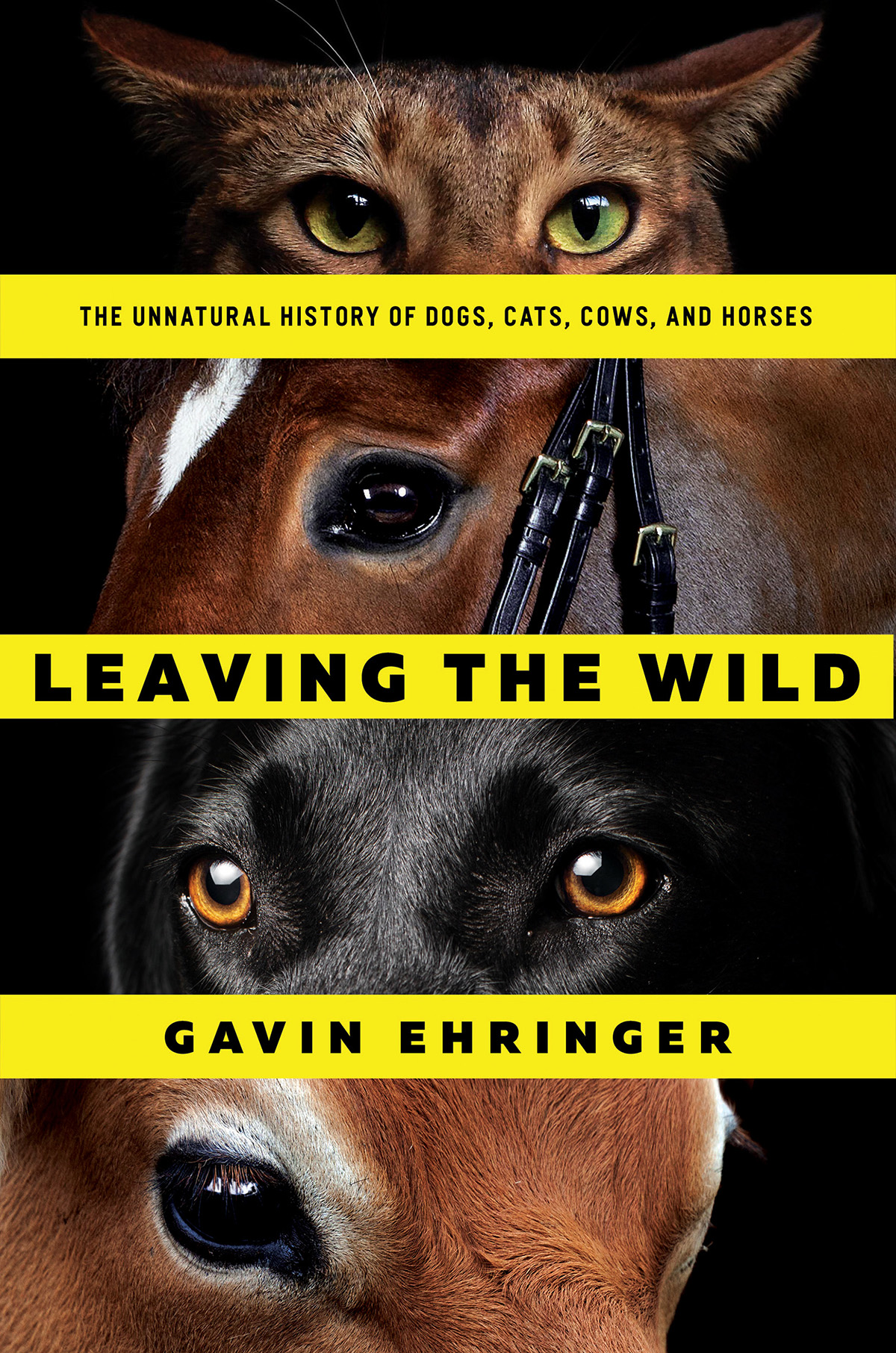

LEAVING

THE

WILD

THE UNNATURAL HISTORY OF

DOGS, CATS, COWS, AND HORSES

GAVIN EHRINGER

LEAVING THE WILD

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2017 by Gavin Ehringer

First Pegasus Books cloth edition December 2017

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-556-2

ISBN: 978-1-68177-606-4 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

www.pegasusbooks.us

In memory of my mother, Alison, and her favorite dog, Tigger.

Thanks for taking care of everyone.

We miss you!

CONTENTS

D ogs, cats, cows, and horses. Not a day of my adult life has passed when I wasnt either working with them or writing about them.

As a college student, I guided horseback rides on a Colorado guest ranch. Afterward, I became a cowboy and helped care for a herd of more than 350 cows and their calves. Ive used stock dogsAustralian shepherds, mainlyin my work, but also competed with them in dog shows and canine Frisbee contests. Barn cats, well, they just came with the territory.

I would go on to become a journalist, writing several thousand magazine articles about domestic animals and the people who bred them, raised them, cared for them, bought them, sold them, raced them, rode them, trained them, and competed with them. Most, like me, adored them, too.

Despite all that, I never stopped to give much thought as to how and why these animals came to live in our homes and barnyards in the first place. Domestication, I assumed, was just something our stone-age ancestors brought about for their own benefit. But my thinking changed when I crossed paths with horse trainer Buck Brannaman.

I met Buck at the Denver National Western Stock Show, a place where domestic animals and people come together in staggering numbers. Over a sixteen-day span, more than 6,500 animals are exhibited there before more than 680,000 visitors.

As anyone who has seen the documentary Buck knows, Brannaman is a cowboy straight from central casting. Hes a tall, weathered guy with a pale, narrow face shadowed by a flat-brimmed, sweat-stained cowboy hat. If that doesnt ring a bell, Buck was also the inspiration for the fictional character Tom Booker in the Robert Redford film The Horse Whisperer . Like Booker, Brannaman has hard, calloused hands, but a tender heart when it comes to horses.

When hes not at his ranch in Wyoming, Buck travels the country giving clinics and demonstrations on natural horsemanship, a Zen-like training philosophy that takes into account life from the horses perspective. Personally, I think its wrong to call him a horse whisperer. Hes more a horse conversationalist. He pays attention to horses, responding to them in the language they understandbody language.

At Denver, I watched Buck work with a chestnut-colored horse in a small, round pen. It was a colt, just a few years old and fresh off the open range. The animal, which belonged to a mutual acquaintance, had not seen a human at close distance until the day he was rounded up and unloaded on the stock show grounds.

With calm patience, Brannaman walked around the pen, letting the colt run and snort as he moved about. Whenever the horse turned to face him, Buck would step back a foot or two, relieving the pressure and rewarding the animal. In less than ten minutes, the horse turned, faced Buck, and stood still. You could see the colts body relax and his face soften. He took a tentative step toward the horseman. Buck referred to this as joining up, but you and I might call it bonding.

Before the seminar was over, Buck had led the colt around the pen with a loose rope, put a blanket and saddle on him, and even ridden the horse in circles without a bridle. Hed convinced the horseor rather, the horse had convinced himselfto put trust in a human as his partner and guide. It was a real-time parable.

That day, Buck gave me a gift of wisdom that stuck in my head. He said, These animals gave up their freedom and their fear of us when they left the wild and came to our campfire. They serve us in many ways. In return, we owe them our care and our understanding.

From that phrase, I conceived the idea for this book.

Leaving the Wild is a book about four common domesticated animals. Each left behind a wild existence in exchange for our care, provision, and protection. Each gives of itself in its own unique ways. I chose Leaving the Wild as a title because it implies willfulness on the animals part. As Buck pointed out, domestication wasnt a one-way street in which people were the only drivers or the only ones who gained something.

Biologist and Pulitzerprize winning author E. O. Wilson aptly said, I know of no instance in which a species of plant or animal gives willing support to another without extracting some advantage in return.

Central to the book is this question: In choosing domestication, what did animals give up, and what did they get? To find out, I spent a year on the road visiting the places animals lived and the people who shared life with them.

My journey began on Thanksgiving Day at the home of a renowned Colorado dog breeder and lifelong friend. After an ethereal turkey dinner followed by homemade pies, I bid my friends goodbye and climbed up into the cab of my recently-bought motor home. I turned the key and it coughed to life.

As we pulled out onto the highway, my Australian shepherd, Onda, hopped up into the passenger seat and looked out at a vast expanse of farmland and the narrow ribbon of highway. On we drove to see Americafrom the animals perspective.

A howling windstorm tried to blow us off the highway all the way to Oklahoma City. Arriving safely, we watched horses that cost more than luxury cars compete for prizes as valuable as houses. From the well-heeled breeders there, we got our first lesson in how human values literally shape animals lives, for better and worse. Then the road took us west, following traces of historic Route 66.

In Amarillo, Texas, we stopped to pet cattle that had been cloned from steaksthe beginning of our education in animal reproduction technology. Next, we watched a stallion earn $160,000 in a single afternoon, just by donating sperm. In the deserts of New Mexico and Arizona, we passed by dairy barns the size of Costco stores.

In California, we stopped in Anaheim to visit Mickey Mouseand learn some things about Disneylands cats. In Carnation, Washington, we took selfies in front of a shrine to the Worlds Most Productive Milk Cow. Then, we drove back to Colorado for the Denver County Fairwhose motto is fairly weird. (It was).

Along the way, we watched dog shows, horse shows, cattle shows, and cat shows. We visited pet breeders homes where animals were born and public shelters where others were killed. We talked to people who fought dogs and people who fought for dogs (and cats, too). We did rounds with veterinarians and ride-alongs with animal control officers. We visited universities and feral cat colonies, and feral cat colonies at universities. And in our downtime, I read research while Onda slept at my feet under my dashboard desktop. He got lots of sleep. The result is the book that youre about to read.

Next page