DEFINING

AUTISM

A Guide to Brain, Biology, and Behavior

Emily L. Casanova

and Manuel F. Casanova

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

Contents

Chapter One

KANNERS CONUNDRUM

AND BERNIES BIOLOGY

THE BEGINNING

Fortunate to have escaped the ravages of war-torn Europe, by 1924 Jewish-born Chaskel Leib Kanner (Leo Kanner: ) found himself working as a physician in the American Midwest. Born in Klekotow, Austria-Hungary, Kanner had been pursuing a career in medicine at the University of Berlin when his studies were interrupted by the turmoils of World War I. As sometimes occurs with the rise and fall of empires, hundreds of thousands of Austro-Hungarians died in battle or from starvation, and those left alive were further consumed by the Spanish influenza ravaging nations. By 1921, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had lost over one million people to war, hunger, and illness, and malnourishment and poverty would continue to remain a problem for the fallen empire. Raised within the Jewish faith, the young Leo Kanner must surely have looked upon America as a promised land.

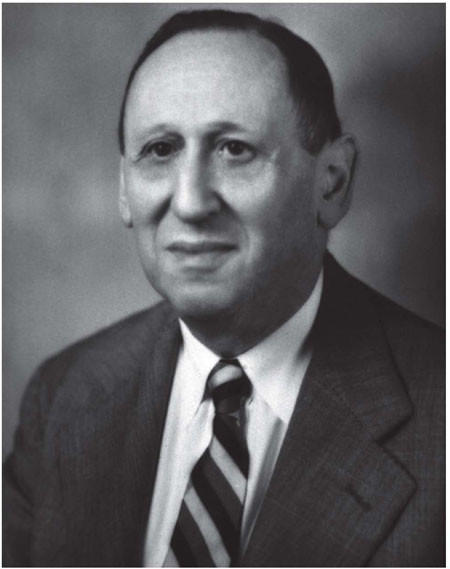

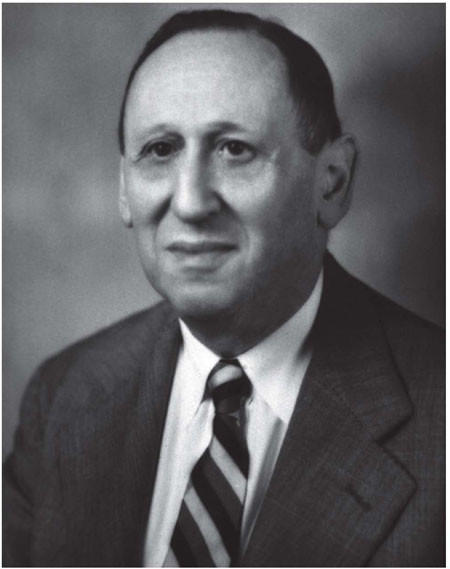

Figure 1.1: Leo Kanner

Like Kanner, many Germans and Austrians fled Europe, settling in America. In order to curb the influx of low-skilled immigrants the United States Congress passed laws establishing quotas and requiring literacy tests for those aliens wishing to enter the U.S. These laws favored well-educated Northern Europeans who, like Kanner, emigrated from their homelands eager for a better life.

By the time Kanner had arrived in South Dakota in 1924, the state had been welcoming immigrants in droves for decades. Austrian and German immigrants tended to settle in the Midwest, living inland rather than on the coasts. As continuing incentive, the earlier Homestead Act of 1862 signed by Abraham Lincoln turned over millions of acres at no cost to private citizens, while most of these homestead acquisitions occurred west of the Mississippi River. Whats more, the development of the railroads provided an easy means of travel for those enticed by the 1870s gold rush.

Although plenty of land was available west of the Mississippi, the Midwestern Plains were an otherwise undifferentiated landscape with little opportunity for cultural expansion. Though the Plains have an unstructured natural beauty of their own, its likely the arctic winter blasts and lack of cultural activities weighed heavily on Kanner, prompting him to make his stay in South Dakota a temporary one, en route to the metropolitan life that better suited his and his wifes European upbringings.

Nevertheless, South Dakota opened new vistas to the academic career of Kanner in unexpected ways. Originally constructed to house German-Russian immigrants, the South Dakota governor acquired two wooden buildings that were eventually transformed into the Dakota Hospital for the Insane. By the time Kanner arrived, the hospital had been renamed the Yankton State Hospital, in recognition of changing perceptions of the term insanity, and the fact that patients with other medical conditions, such as epilepsy, were also hospitalized there.

For over a century, the United States lacked regulatory restrictions concerning the practice of medicine. There was an unspoken belief that people in need of medical attention were consumers who had the right to pursue their care, and the governments role was to protect that right. However, by the 1920s, most states had initiated significant restrictions, allowing only medical schools to teach and practice medicine. Nevertheless, a lack of additional oversight still allowed doctors ample latitude within their practices.

Kanner was originally trained in electrocardiography and cardiophonography. And so during his early days at Yankton he surely felt at odds with his surroundings, working in a field in which he had little training. During that period of history, psychiatrists were often known as al ienists , taken from the French adjective aliene , meaning insane. A cardiologist by training, he likely felt alien in his new hospital post. But this was the impetus he needed to reinvent himself as a psychiatrist, which would change the history of autism forever. Ultimately, he would emerge as the father of American child psychiatry.

THE GERMAN SCHOOL

It was not uncommon for polymaths in the 19th and early 20th centuries to play professional musical chairs, changing specialties throughout their careers. In fact, this tradition was long-standing. The father of American psychiatry, Benjamin Rush, was himself a politician, social reformer, and educator. In 1812, he published the textbook Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon Diseases of the Mind , in which he advocated for the humane treatment of the mentally ill. However, his humanitarian outlook didnt dissuade him from using patients as guinea pigs, testing treatments such as vinegar-wrapped blankets, mercury rubs, cold baths, and extreme blood-letting. In those days, intentions were good but treatment implementation was based on poorly constructed theory rather than empirically based observations, much to the chagrin of the patients being subjected to these treatments.

The German-born Alois Alzheimer (18641915), a noted pathologist, was also regarded as a psychiatrist, in part due to his close association with Emil Kraepelin (18561926), the father of modern psychiatry. Unsurprisingly, this proved to be of mutual influence, since Kraepelins association with Alzheimer and other neuropathologists impacted his concepts of the biological origin of mental conditions such as schizophrenia. This organic tradition was eventually exported to the United States by Elmer Ernest Southard (18761920), a well-known American psychiatrist and neuropathologist, who died tragically young but nevertheless mentored and substantially influenced many prominent thinkers of the day (Casanova, 1995).

A graduate of Harvard Medical School, Southard received his postgraduate education at both the Senckenberg Institute and Heidelberg University in Germany. After returning to the United States, he interned in the pathology department at Boston City Hospital before becoming the president of both the American Medico-Psychological Association and the Boston Society of Psychiatry and Neurology. He also became the Director of the Massachusetts Psychiatric Institute, devoting much of his time to establishing a new nomenclature of psychiatric illness and working to identify brain abnormalities common to dementia praecox (schizophrenia). Along with Mary Jarrett, he founded the field of social psychiatry, which they applied to the benefit of industrial employees. All of this was accomplished before the ripe old age of 43 when he died suddenly of pneumonia, the likely result of workaholic exhaustion. Had it not been for his untimely death, one can only imagine the many achievements he would have continued to realize. Death be not proud of dreams destroyed!

At the beginning of the 20th century, many medical conditions were diagnosed by nonspecific symptoms. These conditions were often systemic in nature and received the descriptive appellation of the Great Imitators or Masqueraders. Various forms of cancers, lupus, multiple sclerosis, and syphilis were all grouped under this rubric. Ultimately, these conditions were diagnosed at autopsy where the pathologist had the final say.

Before the influence of the German School, it was presumed that psychiatric conditions lacked identifiable pathology. Those conditions with distinctive brain pathology were instead thrown into a wastebasket category known as organic brain syndrome . As with many European-born psychiatrists of the day, the influence of the German School had a profound effect on how Leo Kanner perceived and treated mental conditions in his professional career. However, another major influence on Kanner would come from the Swiss-born physician, Adolf Meyer ().

Next page