Europe stands at the crossroads of the Earth. Formed as an archipelago 100 million years ago through the interaction of Africa, Asia and North America, it has been a melting pot in the evolution of the planets animal and plant life ever since.

As landmasses rose and fell, animals great and small found their way across land bridges and seas to the diverse and shifting islands. Europe was once home to elephants and rhinos, giant deer and lionseven the worlds first coral reef. Species arose and became extinct, immigrated and dispersed, hybridised and strengthened. The meeting of ancient humans and Neanderthals in this land of exceptional diversity, rapid change and high energy played a key role in the evolution of our own species.

From amazing fossil finds and the often eccentric scientists who sieved the tonnes of sand to find them, to tectonic shifts, ice ages and the future rewilding of Europe, Tim Flannery tells an enthralling scientific and poetic story of a remarkable continent.

No one tells it better than Tim Flannery. DAVID SUZUKI

Contents

Index

To Colin Groves and Ken Aplin, life-long colleagues, and heroes of zoology.

Natural histories encompass both the natural and the human worlds. This one seeks to answer three great questions. How was Europe formed? How was its extraordinary history discovered? And why did Europe come to be so important in the world? For those, like me, seeking answers it is fortunate that Europe has a great abundance of boneslayer upon layer of them, buried in rocks and sediments that extend all the way back to the beginning of bony animals. Europeans have also left an exceptionally rich trove of natural-history observations: from the works of Herodotus and Pliny to those of the English naturalists Robert Plot and Gilbert White. Europe is also where the investigation of the deep past began. The first geological map, the first palaeobiological studies and the first reconstructions of dinosaurs were all made in Europe. And over the past few years a revolution in research, driven by powerful new DNA studies, along with astonishing discoveries in palaeontology, has enabled a profound reinterpretation of the continents past.

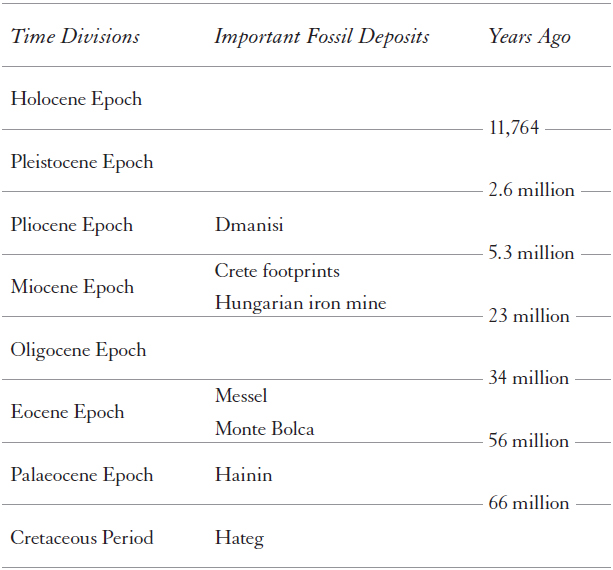

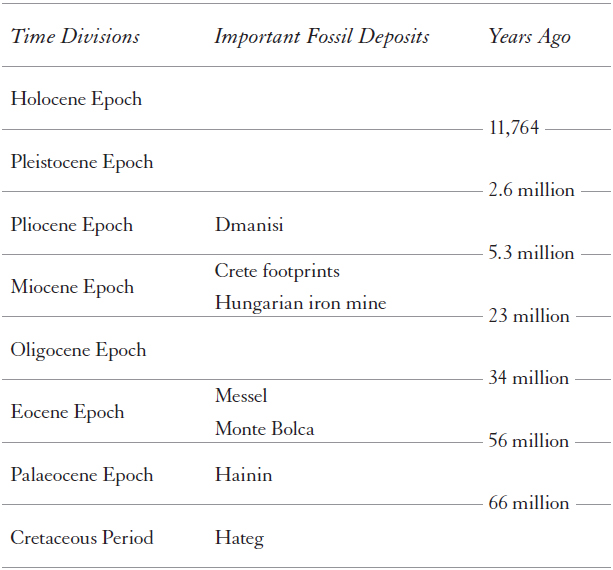

This history begins around 100 million years ago, at the moment of Europes conceptionthe moment when the first distinctively European organisms evolved. Earths crust is composed of tectonic plates that move imperceptibly slowly across the globe, and upon which the continents ride. Most continents originated in the splitting of ancient supercontinents. But Europe began as an island archipelago, and its conception involved the geological interactions of three continental parentsAsia, North America and Africa. Together, those continents comprise about two-thirds of the land on Earth, and because Europe has acted as a bridge between these landmasses, it has functioned as the most significant seat of exchange in the history of our planet.

Europe is a place where evolution proceeds rapidlya place in the vanguard of global change. But even deep in the age of dinosaurs, Europe had special characteristics that shaped the evolution of its inhabitants. Some of these characteristics continue to exert influence today. In fact, some of Europes contemporary human dilemmas result from those characteristics.

Defining Europe is a slippery undertaking. Its diversity, evolutionary history and shifting borders make the place almost protean. Yet, paradoxically, Europe is immediately recognisable. With its distinctive human landscapes, once-great forests, Mediterranean coasts and Alpine vistaswe all know Europe when we see it. And the Europeans themselves, with their castles, towns and unmistakable music, are every bit as instantly recognisable. Moreover, it is important to recognise that Europeans share a highly influential dreamtimein the ancient worlds of Greece and Rome. Even Europeans whose forebears were never part of this classical world claim it as their own, looking to it for knowledge and inspiration.

So what is Europe, and what does it mean to be European? Contemporary Europe is not a continent in any real geographical sense. So defined, Turkey is part of Europe, but Israel is not: the rocks of Turkey share a common history with the rest of Europe, while Israels rocks originate in Africa.

I am not Europeanin a political sense at least. I was born in the antipodesEuropes oppositeas the Europeans once called Australia. But corporeally I am as European as the Queen of England (who, incidentally, is ethnically German). The history of Europes wars and monarchs were drilled into me as a child, but I was taught next to nothing about Australias trees and landscapes. Perhaps this contradiction triggered my curiosity. Whatever the case, my search for Europe began long ago, before I had ever touched European soil.

When I first travelled to Europe as a student in 1983 I was thrilled, certain that I was going to the centre of the world. But as we neared Heathrow, the pilot of the British Airways jet made an announcement I have never forgotten: We are now approaching a rather small, foggy island in the North Sea. In all my life I had never thought of Britain like that. When we landed I was astonished at the gentle quality of the air. Even the scent on the breeze seemed soothing, lacking that distinctive eucalyptus tang I was barely conscious of until it wasnt there. And the sun. Where was the sun? In strength and penetration, it more resembled an austral moon than the great fiery orb that scorched my homeland.

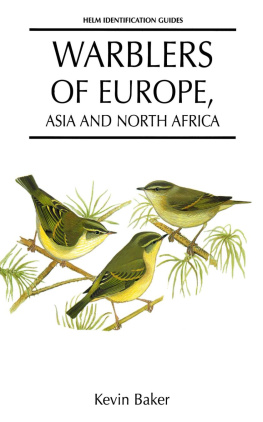

European nature held more surprises. I was astonished at the prodigious size of its wood pigeons and the abundance of deer on the fringes of urban England. The vegetation was so gentle and green in that moist and cushioned air that its brilliant hue seemed unreal. It had very few spines or harsh twigsso unlike the dusty, scratchy scrub at home. After days of peering into misty skies and looking at soft-edged horizons, I began to feel that I was wrapped in cotton wool.

I made that first visit to study in the collections of Londons Natural History Museum. Soon after, I became curator of mammals at the Australian Museum in Sydney, where I was expected to develop a global expertise in mammalogy. So, when Redmond OHanlon, the natural history editor at the Times Literary Supplement, asked me to review a book on the mammals of the United Kingdom, I reluctantly took up the challenge. The work mystified me because it failed to mention the two speciescows and humansthat had long pedigrees in the United Kingdom, and which I had found to be abundant there.

After receiving my review, Redmond invited me to visit him at home in Oxfordshire. I feared that this was his kind way of telling me that my work was not up to scratch. Instead, I was given a warm welcome, and we chatted enthusiastically about natural history. Late at night, after a sumptuous meal accompanied by many glasses of Bordeaux, he conspiratorially ushered me into the garden, where he pointed to a pond. We crept to its edge, Redmond signalling silence. Then he handed me a torch, and, among the waterweeds, I spotted a pale shape.

A newt! My first. As Redmond knew, Australia lacks tailed amphibians. I was as awestruck as was P. G. Wodehouses wonderful creation in the Jeeves novels, fish-faced Gussie Fink-Nottle, who buried himself in the country and devoted himself entirely to the study of newts, keeping the little chaps in a glass tank and observing their habits with a sedulous eye. Newts are such primitive creatures that watching them was like looking into time itself.