Copyright 2016 by Dan Fox

Originally published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in the UK in 2016

Cover design by Patricia Capaldi

Book design by Rachel Holscher

Author photograph Tom Gidley

Coffee House Press books are available to the trade through our primary distributor, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution, .

Coffee House Press is a nonprofit literary publishing house. Support from private foundations, corporate giving programs, government programs, and generous individuals helps make the publication of our books possible. We gratefully acknowledge their support in detail in the back of this book.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Fox, Dan (Daniel Luke), 1976 author.

Title: Pretentiousness: why it matters / Dan Fox.

Description: Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2016.

ISBN 9781566894296 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Performance. | Authenticity (Philosophy) | Creation (Literary, artistic, etc.) | BISAC: ART / Criticism & Theory. | LITERARY COLLECTIONS / Essays. | ART / Popular Culture. | PHILOSOPHY / Aesthetics.

Classification: LCC NX212 .F69 2016 | DDC 700dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015033491

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

for Mum, Dad, Karl, Mark, Ellen, and Osian

Oh boy,

Sometimes it seems like it takes forever,

And then with your friends it takes no effort at all,

Oh it could be a past turn, attachment illusion,

That makes distance between me,

Leading a double, double life.

On the other hand you know it takes some language,

An agreement for the moment making dreams ring true,

So with the resistance comes an angels assistance,

Brings it closer and closer

Leading a double life.

Blue Gene Tyranny, Leading a Double Life (1977)

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

MR. JOHNSON: So Harry says, You dont like me anymore. Why not? And he says, Because youve got so terribly pretentious. And Harry says, Pretentious, moi? Fawlty Towers (1979)

BILLY RAY VALENTINE: Motherfucker, moil?

Trading Places (1983)

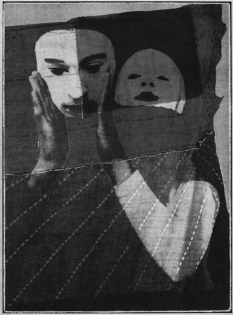

S tart with the basics. (Presumably the least pretentious place to begin.) The Latin praebeforeand tendere, meaning to stretch or extend, gives us the word pretentious. Think of it as holding something in front of you, like actors wearing masks in the ancient Greek theater.

Or imagine yourself on a medieval battlefield, carrying a shield. In heraldry, the term escutcheon of pretense describes the coat of arms of a heraldic heiress, incorporated into her husbands own arms on the death of her father. In the absence of other male inheritors, the heiresss husband would pretend to represent the family. A shield was needed to protect your body in combatheld in front of you, prae tendere, like the actors mask hides the facebut it also carried a design that boasted of your power and political authority. Your pretense was your protection, and could also make you into a target. (Since the fourteenth century, the Russian army has used a strategy of deception they call maskirovkasomething maskedto hide, deny, or divert attention away from real military maneuvers.)

In politics the claimant to a throne or similar rank was known as a pretender. Upheavals in England, Scotland, and Ireland brought about by the Glorious Revolution in 1688, for example, saw the overthrow of the last Stuart king, the Catholic James II, by the Protestants William and Mary. Subsequently, two pretenders, James IIs son and grandson, made claims to the English crown. (The most famous of these was the Young Pretender, Charles Edward Stuart, also nicknamed Bonnie Prince Charlie.) To be called a pretender was not necessarily an insult; the issue was the legitimacy of the claim you held before you, prae tendere. Authority was recognized on the basis of your political allegiance and religious belief, not questions of truth or falsity. This pretense was not an act. It was a matter of blood and God.

Go back to the actor and the mask. In classical Greek theater the word hypokritsfrom which we get hypocrisywas the standard term for actors, deriving from the words hyp (under) and krisis (decide, distinguish, or judge). It was a way of describing a dissembler, the faces of the mask and the actor beneath it. When St. Paul, in his epistle to the Romans, wrote Let love be not hypocritical, he used the word in this Greek sense, meaning actor. Paul meant that love should not hide itself behind a mask representing love, or use words signaling it insincerely.

Man is least himself when he talks in his own person, wrote Oscar Wilde. Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth. Well, maybe. It depends on the time and place. Theater, cinema, and broadcasting provide the professional license to wear one. We derive pleasure from the deceits of the stage illusionist, whose acts of fakery we pay money to watch. (Magician James The Amazing Randi describes himself as an honest liar.) In carnival and ritual too, the mask is socially sanctioned. Outside these fields the actors mask is suspect. So we smear it with the brush of immaturity, dismissing it as pretending.

Pretending is what kids do to figure out the world. Children do not put on airs. A child might be precociousfrom the Latin prae, before, and coquere, meaning to cook, that is, precooked or ripened earlybut its rare that a child is called pretentious. That insult is reserved for the pushy parents; pretending is whats done at the kids table, pretension goes on over the wine and cheese course with the grown-ups. Pretending reminds adults of childish things long put away, of imaginary friends, and of the companionship found in favorite teddy bears and dolls, in toys we imagined to have distinct personalities and the stories we swaddled them in. To pretend is to live in denial of real grown-up problems. Its childs play.

And a play is also what professional actors are employed to make onstage in theaters. Acting is a reflex, a mechanism for development and survival, writes theater director Declan Donnellan in The Actor and the Target. It is not second nature, it is first nature and so cannot be taught like chemistry or scuba diving. Acting is a tool of every social interaction we have from birth. Peek-a-boo, says Donnellan, is the first play a baby enjoys,

when its mother acts out appearing and disappearing behind a pillow. Now you see me; now you dont! The baby gurgles away, learning that this most painful event, separation from the mother, might be prepared for and dealt with comically, theatrically. The baby learns to laugh at an appalling separation, because it isnt real. Mummy reappears and laughsthis time, at least. After a while the child will learn to be the performer, with the parent as audience, playing peek-a-boo behind the sofa.... Eating, walking, talking, all are developed by observation, performance, and applause. We develop our sense of self by practicing roles we see our parents play and expand our identities further by copying characters we see played by elder brothers, sisters, friends, rivals, teachers, enemies or heroes.

Next page