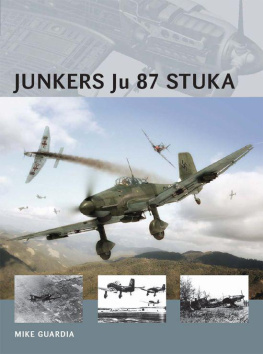

AIR VANGUARD 15

JUNKERS Ju 87 STUKA

MIKE GUARDIA

CONTENTS

JUNKERS Ju 87 STUKA

INTRODUCTION

During the early days of Blitzkrieg, few aircraft could inspire more terror than the Junkers Ju 87. Nicknamed the Stuka, (an abbreviation of Sturzkampfflugzeug the German word for dive-bomber) it quickly became a sign of Nazi air power. With its inverted gull wings and fixed landing gear, the Stuka was one of the most recognizable aircraft of the ETO. Its most potent weapon, however, was psychological. Its dive-activated air siren, known as the Jericho Trumpet, produced a dreadful wail that could create panic in even the most disciplined of ground units.

Designed by aerospace engineer Hermann Pohlmann, the Stuka had many features that were innovative for the time, including automatic pull-up dive brakes which could recover the plane from a dive if its pilot blacked out from the acceleration. Debuting on September 17, 1935, the Stukas introduction came at a time when Germany was resurging from the turmoil of the Weimar Republic. As Adolf Hitler rebuilt Germanys war machine under the Nazi banner, the Luftwaffe began stacking its arsenal with a fresh inventory of tactical fighters, fighter-bombers, and long-range bombers. The Stuka was accepted into service in 1936, just as the concept of dive-bombing was beginning to take hold in the Wehrmacht. By that time, it became apparent that dive-bombers had better accuracy than level bombers and performed better when engaging mobile ground targets.

The Stuka made its combat debut in 1936 with the Luftwaffes Legion Condor during the Spanish Civil War. Three years later, at the outset of World War II, the Stuka spearheaded the German air campaign over Poland, Norway, and the Low Countries. Around this time, the Ju 87 was also exported to the Bulgarian Air Force, Royal Romanian Air Force, and the Italian Regia Aeronautica. The Stuka fought again during the Battle of Britain, but the aerial skirmishes over England revealed several design and performance problems. Its poor maneuverability, low speed, and lack of defensive armaments made it easy prey for Allied fighters. Following the air campaign over Britain, the Stuka required heavy fighter escorts to operate effectively. Despite these setbacks, however, the Stuka went on to achieve success in the Balkans, North Africa, and along the Eastern Front before the Soviets achieved air superiority over the region.

Once the Allied air forces established superiority over the European mainland, the Stukas effectiveness waned yet again. Nevertheless, Junkers kept the plane in production until 1944 and it remained in service until V-E Day. During the final years of the conflict, however, the Stuka was largely replaced by ground-attack variants of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. Throughout its service history, nearly 6,500 Ju 87s were built. Following the end of the war, the Luftwaffe was disbanded and the remaining Stukas, along with the rest of the Nazi-era aircraft, were retired. Today, only a handful of Stukas survive and none are flyable.

The Junkers Ju 87 Stuka was one of the most recognizable planes of the ETO. During the early days of Blitzkrieg, the Ju 87 spearheaded the aerial campaigns over Poland, Norway, France, and the Low Countries. Although a formidable dive bomber, the Stukas most potent weapon was psychological: the dive-activated air siren, known as the Jericho Trumpet, produced a dreadful wail that struck fear into the hearts of many Allied troops. (US Navy)

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

The story of the Ju 87 begins with the Luftstreitskrfte of World War I. Barely a decade after the Wright Brothers inaugural flight, the concept of using airplanes for military operations had spread throughout Europe. More agile and maneuverable than the hot air balloons of the Franco-Prussian and Napoleonic Wars, the fixed-wing airplane provided a resilient and easily reusable means of performing aerial reconnaissance. However, Kaiser Wilhelms military planners soon discovered that the airplane could deliver a devastating attack from the third dimension.

Throughout World War I, Germany relied heavily on two classes of bomber aircraft, the fixed-wing Gotha series and the military-grade zeppelins. Each, however, met with limited success on the frontlines. The Gotha variants were limited in number and their slow maneuverability made them easy prey for Allied fighters. The zeppelins, however, delivered great results during the early bombing campaigns over Britain and Poland. In fact, the zeppelins were initially immune to the enemys air defenses. Because the pressure of the lifting gas was comparable to the ambient air, the bullet holes had little to no effect. However, once the Allies began using incendiary bullets, the zeppelins flammable hydrogen gas made them vulnerable targets. To boot, zeppelins were notoriously slow, clumsy, and frequently strayed off course. As they wandered into Allied airspace, they were frequently shot down by French and British fighters. By the end of the war, airships were declared useless as war machines.

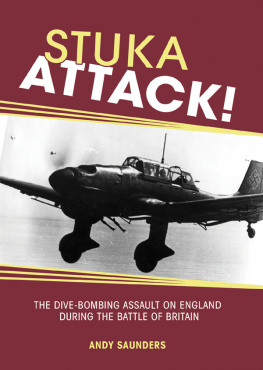

The Stuka performs its signature dive during the Battle of Britain. To deliver its bombs on target, the Stuka would turn itself upside down and nose itself into a diving maneuver, sometimes at angles in excess of 80 degrees. It was during the Battle of Britain, however, when the Luftwaffe discovered the Stukas shortcomings. Against an organized aerial resistance, the Stukas slow airspeed and poor maneuverability made it an easy target for Allied fighters. (Royal Air Force)

Meanwhile, the concept of dive-bombing remained little more than an afterthought. The Royal Air Force had experimented with the concept using their modified SE5a planes and Sopwith Camels but quickly decided that the benefits of dive-bombing did not outweigh the anticipated losses that a unit would incur if it engaged in such tactics.

However, the Germans perception of dive-bombing was decidedly different. They determined that medium and heavy horizontal bombers could deliver the best results against strategic targets (i.e. enemy cities, infrastructures, and places of industry targets that could be engaged from higher altitudes). Dive-bombers, on the other hand, would be ideal against tactical targets (i.e. troop formations, supply depots, and field fortifications). Theoretically, a dive-bomber could deliver pinpoint accuracy against these targets, while itself presenting a minimal target to the enemys air defenses.

Although crippled by the disarmament terms of the Treaty of Versailles, German aircraft companies like Junkers and Heinkel began looking for ways to circumvent the language of the treaty. Junkers, for instance, opened a Swedish subsidiary known as Flygindustri. Under the guise of developing civil aircraft in its straw man subsidiary, Junkers developed a prototype fighter known as the K 47. A two-seat fighter, the K 47 first flew in 1929 and could carry a 100kg bomb load (typically eight 12.5kg fragmentation bombs). The K 47 underwent extensive trials at the secret German air facility at Lipezk (in the Soviet Union) to test its suitability as a dive-bomber. The K 47 performed remarkably well in these early tests, but its high price tag precluded it from joining the ranks of Germanys small inter-war arsenal.

Next page