Copyright 2018 by Ian Hodder.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Designed and set in Hoefler Text by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018939537

ISBN 978-0-300-20409-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 978-0-300-24039-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2.

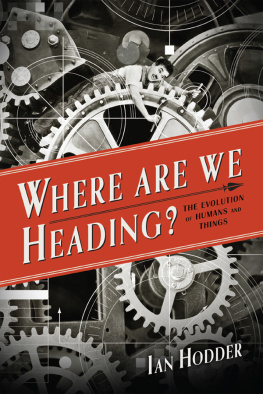

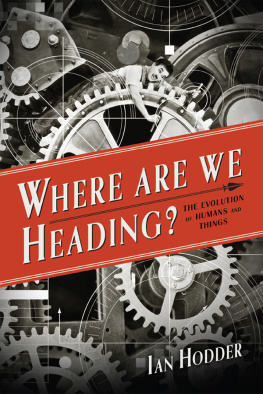

Where Are We Heading?

The Evolution of Humans and Things

Ian Hodder

Contents

FOUNDATIONAL QUESTIONS IN SCIENCE

At its deepest level, science becomes nearly indistinguishable from philosophy. The most fundamental scientific questions address the ultimate nature of the world. Foundational Questions in Science, jointly published by Templeton Press and Yale University Press, invites prominent scientists to ask these questions, describe our current best approaches to the answers, and tell us where such answers may lead: the new realities they point to and the further questions they compel us to ask. Intended for interested lay readers, students, and young scientists, these short volumes show how science approaches the mysteries of the world around us and offer readers a chance to explore the implications at the profoundest and most exciting levels.

For Lynn

Preface

If you wish to make an apple pie truly from scratch,

you must first invent the universe.

CARL SAGAN (ASTRONOMER AND WRITER

[19341996]), COSMOS

T HIS BOOK deals with a problem that has bedeviled archaeologists, anthropologists, social theorists, philosophers, and evolutionary biologists: Does human evolution have a direction? If so, why? These questions dominated debate in the nineteenth century and in the mid-twentieth century, but consensus today is that biological evolutionary development is nondirectional. The same holds for human cultural development: Humans, their cultures, and their societies change or evolve, but they are not thought to evolve in any overall direction. One reason for this view is that directional arguments lead to the notion that some societies or cultures are more advanced than others. Because such theories were found to be repellent, there were long periods in which evolution was rejected in favor of diffusion as a motor for change.

But we have an urgent need to reconsider the assumption that cultural and social evolution are nondirectional. There is clear archaeological evidence for an overall trend in human evolution toward greater dependence on and entanglement with things. As a species we keep producing more and more stuff. This brings significant changes in many areas of life, but our dependence on an increasing mass of things has ravaged the world in which we live, leading to global problems such as possibly irreversible climate change. We need some insight into why our species is heading in this direction.

I should make absolutely clear that I am not concerned in this book with arguments for intelligent design. This book is not about invisible hands or divine destinies. I am interestedin this bookonly in tangible evidence and the practical intersections of humans and things that have led to long-term change.

My argument could be called evolutionary. What might this mean? Two main types of evolutionary theory have dominated science over the last two centuries. In the nineteenth century, social evolutionists argued that societies progressed toward advanced urban industrial systems; related arguments emerged again in the mid-twentieth century and are today phrased in terms of movement toward complexity. Such arguments are directional but also teleological in the sense that societies are seen as moving toward some end or goal. The problem is that the end (the telos of advanced complexity) is also the cause of change (humans become more complex because they want to, or human societies become more complex because it is the nature of complex systems to become more complex). This approach does not explain very much.

The other main type of evolutionary theory is inspired by Darwin, and over recent decades it has come to play an important role in accounts of long-term social and cultural change, sometimes Darwinian approaches usually eschew directional change; rather, change comes about through variation, selection, and transmission. There is no reason that societies should move in one overall direction; they should just adapt to changing environments.

The trouble with social evolutionary theories is that they are teleological. The trouble with Darwinian theories is that they do not explain the archaeological evidence for overall directional change. This book argues that it is possible to find a third way; it is possible to build a theory of directional change without returning to the dangerous teleologies of nineteenth-century thought. We could call this approach evolutionary, but I have largely avoided using that term in the text of this book because it has come to be closely associated with biological evolution. While I integrate biological evolution into my notion of entanglement in this book, I do not wish to reduce entanglement and long-term change in entanglement to biological evolution or to the metaphor of biological evolution.

Many archaeologists and sociocultural anthropologists dislike the word evolution when it is applied to their field. Some of this dislike concerns the idea of progress toward higher-level societies, while some of it concerns the lawlike, reductionist nature of some evolutionary arguments. It would be nice to be able to use other terms, such as development, but these also have their problems. My main reason for using the term evolution at all in this book is that I wish to focus on the sense of unrolling that lies in the words origin. Long before Darwin, it was used to refer to the unfolding of events. In arguing for a directionality in human evolution, I am using the word in its sense of unrolling, as well as invoking the idea of gradual change. But I also wish to rescue the term from its associations with progress and lawlike development. Another aspect of its etymology refers to how things turn outhence to the contingency of developmental change. In this book I propose to redefine human evolution as directional (path-dependent) but also contingent and complex (nonreductive).

My goal is to find a third way between biological and sociocultural evolution by focusing on things. Following much current research in cognitive evolution, materiality studies, and archaeology, I argue that human being is thoroughly dependent on made things. Since the first tool, humans have always dealt with problems by changing things. This dependence on things has produced our humanity, but it has also entrapped us in yet greater dependence. Things are unstable: They have their own processes that entangle humans into their care. For example, humans domesticated wheat, came to depend on it, and still do today. But wheat, once domesticated, can no longer readily reproduce itself. So dependence on wheat has entangled humans into the increased labor of plowing, sewing, weeding, harvesting, and processing. We increasingly get caught in a double binddepending on things that come to depend on us, so that we must labor and develop new technologies.

Next page