PATENTS

Ingenious Inventions

How They Work and How They Came to Be

BEN IKENSON

Copyright 2004 by Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-57912-367-3

eISBN-13: 978-1-60376-272-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request

Published by

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

151 West 19th Street

New York, New York 10011

Distributed by

Workman Publishing Company

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many people are to be acknowledged in the making of this book. First, thanks to my editor, Laura Ross, whose creativity is as impressive as her motivational skill. Reeve Chace provided superb preliminary text support. Copyeditor/Fact Checker/Photo Researcher/Life Saver Sylvia Helm, along with Dan Armstrong and Stuart Armstrong, offered remarkable assistance throughout. The prodigious design talents of Scott Citron brought the book to life, and my publisher, J. P. Leventhal, along with many others at Black Dog, helped this labor bear fruit.

I would also like to thank a number of people who supported my efforts in one way or another: Melanie Ruiz, Billy Kiester, Mark Olague, Tamara Ward, Matt Huggler, Patrick Durham, Betsy Lordan, Doug Hobbs, Mary Leonard, Alan Rothschild, and the professionals at the U.S. Patent and Trade Office.

INTRODUCTION

Hell, there are no rules herewere trying to accomplish something.

Thomas A. Edison

FROM THE FIRST WHEEL WAY BACK WHEN, our inventions have been what move us forward. Our evolution still depends largely on the tools we create, great ideas made manifest, improved upon, occasionally perfected. Everywhere, we live in a world of ideas materializing.

As of this writing, a yellow bulldozer/backhoe hulks outside of my apartment window, large trucks beep in reverse; metal blades shear through pavement; bulldozers scoop giant concrete chunks from the street as easily as a boy scoops up a handful of marbles; a construction manager shouts into a cell phone. They are replacing old waterlines that were surely an innovation in their day. When its all said and done, the people living on this block will shower and wash, safe from the threat of lead poisoning from the old piping. In the meantime, I throw a CD into the stereo to drown out the ruckus and sit down at the laptop computer to tap out flurries of e-mail over the Internet. I do not have far to go to find inspiration for a book about human ingenuity.

As civilizations emerged, so did systems of economy that rewarded innovation, ultimately attempting to protect that abstraction so crucial to any alleged meritocracy, intellectual property. Today, these are called patent and trade offices, and many countries have established sophisticated systems of laws which they help to uphold. A patent protects a persons idea so that he might rightly profit from it, thereby encouraging innovation as a means to prosperity.

In this book, many ideas, large and small, are explored and celebrated. Inventions tend to reflect our needs and desires, sometimes even our fears; they are inspired by the drive to improve life, make it more manageable, more efficient, and even more fun. If necessity is the mother of invention, then madcap ingenuity must be its errant father. How does one explain the success of the Slinky or the perennial attraction of the Chia Pet without careening happily towards the absurd?

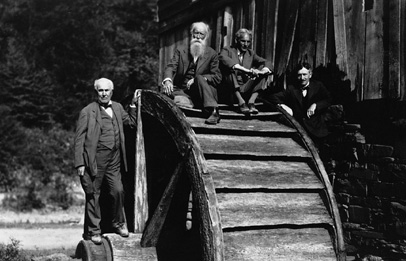

Four close friends, Thomas Edison, John Burroughs, Henry Ford, and Harvey Firestone, inspect an antique mill wheel.

As a broad survey, this book celebrates all branches of the patent family tree. Be it Bubble Wrap, barbed wire, or the artificial heart, a patent reveals our values, our idiosyncrasies, and the spirit of invention that is such a fundamental part of human nature. This illustrated collection of patents offers insight into some of the defining principles of each invention represented, the inventors original intention (sometimes wildly different from its ultimate use), and the peculiar visionary genius these singular patents were issued to protect. Many of the items were patented in an inventors home country in addition to the United States. For the sake of consistency, this book relies mostly on the patent language and illustrations obtained from the U.S. Patent Office.

Since Thomas Jefferson handed out the first patent in 1790, the United States Patent and Trademark Office has granted more than six and a half million patents in the effort to foster scientific advancement and economic prosperity. These pages represent only a tiny yet significant fraction of these.

I hope this book does more than reflect upon the particular genius of some well-known objects and ideas; I hope it stirs within the reader that innate desire to invent. Like evolution, one invention often gives rise to anotherthe replacement of the water pipes beneath my street is a good example of this. That I can once again hear the ruckus outside because my old CD player is skipping is yet another. Invention is a constant work-in-progress to which this book pays respectful tribute.

Ben Ikenson

PATENTS: A HISTORY

Congress shall have the power to promote the progress of science and useful arts by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.

Article, Section 8, U.S. Constitution

The Beginning

Although many of the United Statess original thirteen colonies upheld some form of patent law, the original concept of the patent, as we now know it, was not a uniquely American idea. In 1449, King Henry VI of England awarded a patent to a John of Utynam for his distinctive way of manufacturing stained glass. It soon became clear that offering inventors some protection of their ideas benefited not only the individuals who came up with new things, but helped contribute to the economic growth of whole countries. So, when the settlers from England began arriving in America, they brought the concept of patent law with them.

So strong was the belief of the founding fathers in the usefulness of patent, trademark, and copyright law that tenets of the principle were written into the Constitution: Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution, the Intellectual Property Clause, is the basis upon which our patent laws are built. In fact, the contemporary patent office is founded on three acts passed during our countrys early years: the Patent Act of 1790, the Patent Act of 1793, and the Patent Act of 1836.

Thomas Jefferson was among the group that led the charge to establish the first patent laws in the United States in 1790. The Patent Act of 1790 stipulated that all applications must be accompanied by a model of the invention, since Jefferson felt that patents should only be issued for tangible, physical things, not ideas. The first patent act also explicitly prohibited foreign patents from winning protection on U.S. soil. Samuel Hopkins of Pittsford, Vermont, was the recipient of the very first U.S. patent awarded by the new office for his improvement in the making of Pot Ash.

Next page