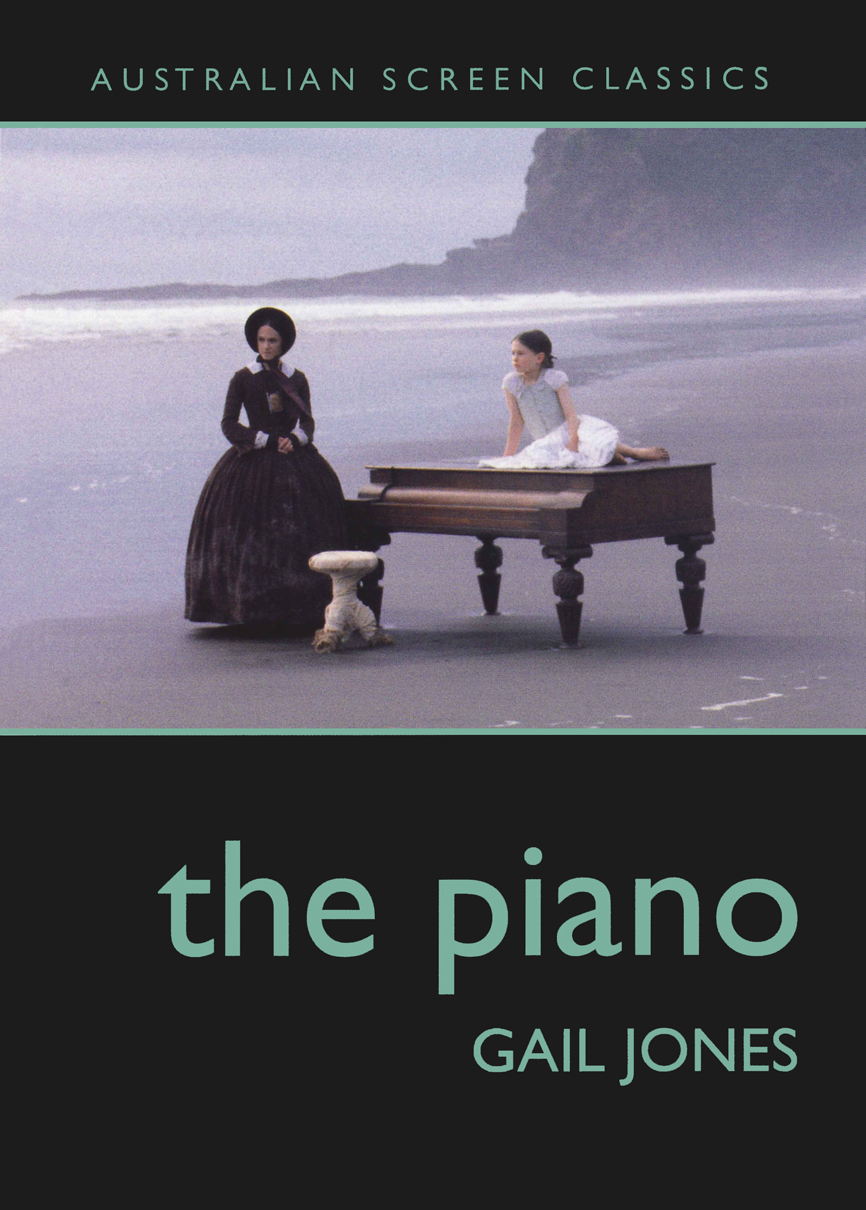

GAIL JONES

Gail Jones teaches cinema, literary and cultural studies at the University of Western Australia. She is also the author of two books of short stories: The House of Breathing (1992) and Fetish Lives (1997), and four novels: Black Mirror (2002), Sixty Lights (2004), Dreams of Speaking (2006) and Sorry (2007). Her work is widely translated and the recipient of several literary awards.

AUSTRALIAN

SCREEN CLASSICS

Jane Mills

Series Editor

Our national cinema plays a vital role in our cultural heritage and in showing us at least something of what it is to be Australian. But the picture can get blurred by unruly forces such as competing artistic aims, inconstant personal tastes, political vagaries, constantly changing priorities in screen education and training, and technological innovations and market forces.

When these forces remain unconnected, the result can be an artistically impoverished cinema and audiences who are disinclined to seek out and derive pleasure from a diverse range of films, including Australian ones.

This series is a part of screen culture which is the glue needed to stick these forces together. Its the plankton in the moving image food chain that feeds the imagination of our filmmakers and their audiences. Its what makes sense of the opinions, memories, responses, knowledge and exchange of ideas about film.

Above all, screen culture is informed by a love of cinema. And it has to be carefully nurtured if we are to understand and appreciate the aesthetic, moral, intellectual and sentient value of our national cinema.

Australian Screen Classics will match some of our best-loved films with some of our most distinguished writers and thinkers, drawn from the worlds of culture, criticism and politics. All we ask of our writers is that they feel passionate about the films they choose. Through these thoughtful, elegantly-written books, we hope that screen culture will work its sticky magic and introduce more audiences to Australian cinema.

Jane Mills is a Senior Research Associate at the Australian Film, Television & Radio School, a member of the Board of Directors of Cinewest, and is the recipient of a scholarship at the Centre for Cultural Research, University of Western Australia. She is currently writing a book about the relationship between global and local cinemas.

acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Series Editor, Jane Mills, for her intelligent, sophisticated and clever attention to this text and for sharing generously her cinephilic pleasure from which such labour derives. I also wish to thank the students at the University of Western Australia with whom, over several years, I have discussed The Piano; their insights and provocations form part of my reading of this film. I am also grateful the artists and academics at Camargo Foundation, Cassis, who patiently watched a screening with me, and to Lauren, Michelle and Kyra for their enthusiastic engagement at a final viewing.

The Series Editor would like to thank the Australian Film, Television & Radio School, especially the unfailingly supportive librarians, and everyone at the Dr What video store of Bondi Junction.

For my mother

The sea, the sea

Jane Campion once spoke of a movie, Ebb, which she considered, but never made:

It was an imaginary story about a country where one day the sea leaves, never returns, and the way in which the people have to find a spiritual solution to this problem. The natural world had become artificial and unpredictable and the film spoke about faith and doubt. The inhabitants of this country had developed a certain form of spirituality, hearing voices, having visions.

There is something strangely compelling in this mini-narrative, and in oblique ways it speaks of the concerns of The Piano. A movie premised, hypothetically at least, on loss and redemption, on a spiritual struggle to deal with the bewildering subtraction of something that had seemed otherwise essential, The Piano, also, attempts to solve certain conditions of absence and estrangement, the world made unfamiliar, the challenge of recovery, of forms of damage that can only be negotiated by visions. Curiously, too, The Piano works with a sensibility of immersion, as if in a dialectical gesture willing the flow that Ebb hypothetically cancelled. According to cinematographer, Stuart Dryburgh,

Part of the directors brief was that we would echo the films element of underwater in the bush. Bottom of the fish tank was the description we used for ourselves to define what we were looking for. So we played it murky green-blue.

What symbolic sea-space is this? Why the wish for a fish-tank filter of murky aquamarine? And what directorial command, therefore, to obliterate visually, if only in certain scenes or as a suggestive and subliminal trace, the necessary division of earth and ocean? The nineteenth-century critic John Ruskin once famously described the sea as an irreconcilable mixture of fury and formalism, expressing exasperation at its representational challenge. What is worth exploring, I think, are the ways in which The Piano is hinged on just this kind of contradiction: an aesthetic of both containment and excess, the rhythmical unrolling of images, recurring with wave-like regularity, but also their overlapping, an interior turbulence, a sense of spill into dimensions of sublimity and vastness. Every movie, of course, is a motion picture, a system of fluctuation and continuous mobility.

Revising Ebb, the look of The Piano is thus often submarine: there is a watery quality to many of the shots, and New Zealand, the principal setting, is remade as a perilous and drenching heterotopia, a place not for touristic or colonial satisfactions of the picturesque, but somewhere other-worldly, deep, bluish, strange, somewhere, indeed, that might ultimately suck one under, or dissolve the self into place in disturbing ways. The sea is recurrently evoked, prayed to in a Maori ritual, photographed as bands of light and dark, or thundering dramatically at the limits of the visible world.

Add to this Michael Nymans famously hypnotic score, which swells and rises, ebbs and flows, saturates the crucial scenes in an irresistible tonal wash. The soundtrack, that is to say, is also fluid; its motifs recur in a kind of compulsive repetition, based in part on the composers knowledge of the forms of baroque rounds and canons. The music crests and falls and superimposes; it moves with broad tidal sweep, just as waves do. The climax of the narrative, such as it is, is the heroines near-drowning. She descends to expressionist film-making, lapis light and a lush enveloping score, seeming to go down and down, way into shadowy depths, so that her ascent and recovery seem almost a continuity mistake. (More of that later.) And the movie ends, as viewers may puzzle-headedly recall, with an image of the heroine, Ada, suspended beneath the ocean, swaying, darkly obscure, within light-shot currents. Her dress oddly resembles a domed sea creature, ballooning around her. She is filmed from below, as if the camera has finally sunk to the ocean floor, as if that is where the directorial and cinematic consciousness of