There is a hue and cry for human rights, they said, for all people, and the Indigenous people said: What of the rights of the natural world? Where is the seat for the buffalo or the eagle? Who is representing them at this forum? Who is speaking for the water of the earth? Who is speaking for the trees and the forests? Who is speaking for the fishfor the whales, for the beavers, for our children?

Chief Oren Lyons Jr ., Faithkeeper of the Onondaga tribe of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Nation

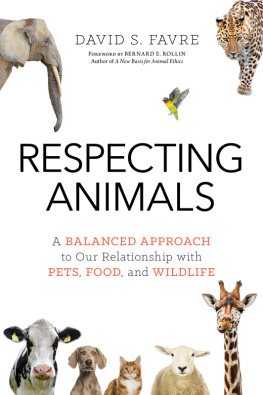

Humans today have a deeply troubled relationship with other animals and species, and with the ecosystems upon which all life on Earth depends. We purport to love animals but regularly inflict pain and suffering upon them. Every year, according to the UNs Food and Agriculture Organization, humans kill over 100 billion animalsfish, chickens, ducks, pigs, rabbits, turkeys, geese, sheep, goats, cattle, dogs, whales, wolves, elephants, lions, dolphins, and more. Scientists are in agreement that human actions are causing the sixth mass extinction in the 4.5-billion-year history of the planet. Species are being declared extinct every year, and we are pushing thousands more to the brink of oblivion. Humans are damaging, destroying, or eliminating entire ecosystems, including native forests, grasslands, coral reefs, and wetlands. Ancient, complex, and vital planetary systemsthe climate, water, and nitrogen cyclesare being disrupted by our actions.

Homo sapiens emerged from Africa less than 200,000 years ago. Thanks to their fertility, adaptability, and ability to use technology, our ancestors colonized the entire Earth around 12,000 years ago, including the continents we now call Europe, Asia, Australia, North America, and South America. Over the course of the past two centuries, our population has exploded, growing from one billion in 1800 to 7.5 billion today. While birth rates are falling the world over, the latest UN estimates indicate that increased longevity and improved health are pushing us toward a population of ten billion people by 2050.

To meet the needs and desires of this booming population, the global economy has also exploded, from a worldwide GDP of about one trillion dollars a century ago to more than 100 trillion dollars today. Much of this economic growth has been driven by ever-increasing human appropriation of land, forests, water, wildlife, and other natural resources.

Our environmental impact has grown exponentially because of population and economic growth. Humanitys collective ecological footprint is estimated to be 1.6 Earths, meaning we are using natural goods and services 1.6 times faster than they are being replenished. This is largely the result of high levels of consumption in wealthy nations. Geologists, a group hardly known for hyperbole, have named this geological era the Anthropocene because of the scope and scale of human impacts on the Earth.

Our ongoing use and misuse of other animals, species, and nature is rooted in three entrenched and related ideas. The first is anthropocentrismthe widespread human belief that we are separate from, and superior to, the rest of the natural world. Through this superiority complex, humans see ourselves as the pinnacle of evolution. The second is that everything in nature, animate and inanimate, constitutes our property, which we have the right to use as we see fit. The third idea is that we can and should pursue limitless economic growth as the paramount objective of modern society. Anthropocentrism and property rights provide the foundations of contemporary industrial society, underpinning everything from law and economics to education and religion. Economic growth is the principal objective for governments and businesses, and it consistently trumps concerns about the environment.

These ideas have a long history. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that animals lacked souls and reason and therefore, as inferior creatures, were appropriately used as resources by man. As he wrote in Politics, Plants exist for the sake of animals, and animals for the sake of mandomestic animals for his use and food, wild ones for food and other accessories of life, such as clothing and various tools. Since nature makes nothing purposeless or in vain, it is undeniably true that she has made all animals for the sake of man. Aristotle also worked with Plato to develop the concept of a hierarchical ladder of existence that ranked animals and plants. Later Christian philosophers built upon this, devising the Great Chain of Being that placed humans near the top of the ladder, just below God and the angels. Non-human animals languished below us, while snakes, insects, and creatures incapable of movement occupied even lower rungs. The chain imposed a strict hierarchy on all life forms.

Genesis, the Christian creation story, states that God made humans in his image and granted us dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth. Humans were given clear instructions: Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it. Not all Christians viewed the rest of creation as subject to human dominion. St. Francis of Assisi advocated for the equality of all creatures, referring to the sun, the Earth, the water, and the wind as his brothers and sisters. St. Francis, however, was an outlier.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, some of historys most influential thinkers reinforced the anthropocentric perspective, and the place of animals in human society took a turn for the worse. Non-human animals were deemed unable to speak, reason, or even feel. French philosopher Ren Descartes forcefully expressed the idea that animals are mere machines and wrote, The reason animals do not speak as we do is not that they lack the organs, but that they have no thoughts. Descartes concluded, Man stands alone. Similarly, German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote, Animals are not self-conscious and are merely a means to an end. That end is man... our duties toward animals are merely indirect duties toward humanity.

A contrary and more progressive attitude toward animals was suggested by nineteenth-century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham. He concluded that the critical moral question for how we should treat animals is not Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? In his view, some animals could indeed feel pain, and therefore had the right not to be harmed. Benthams ideas did not prevail in his own time, but they eventually influenced Peter Singer, author of the 1975 best-seller Animal Liberation that kickstarted the modern animal rights movement.

Anthropocentric ideas are still in vogue today. In his 2004 book, Putting Humans First: Why We Are Natures Favorite, libertarian philosopher Tibor R. Machan wrote, Humans are more important, even better, than other animals, and we deserve the benefits that exploiting animals can provide. Because humans are the most important species, Machan continued, it is right to exploit nature to promote our own lives and happiness.

The notion of human superiority is even entrenched in landmark international environmental agreements. The first global eco-summit, held in Sweden in 1972, produced the Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (more commonly known as the Stockholm Declaration). It proclaimed, Of all things in the world, people are the most precious. The 1992 Earth Summit in Brazil resulted in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, which stated, Human beings are at the centre of concerns for sustainable development.