Contents

ALSO BY MICHAEL P. BRANCH

Raising Wild: Dispatches from a Home in the Wilderness

R OOST B OOKS

An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

roostbooks.com

2017 by Michael P. Branch

Anecdote of the Jar from The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens by Wallace Stevens, copyright 1954 by Wallace Stevens and copyright renewed 1982 by Holly Stevens.

Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC and by Faber & Faber Limited. All rights reserved.

How to Like It from Velocities: New and Selected Poems, 19661992 by Stephen Dobyns, copyright 1994 by Stephen Dobyns. Used by permission of Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC and by Harold Ober Associates.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

constitutes a continuation of the copyright page.

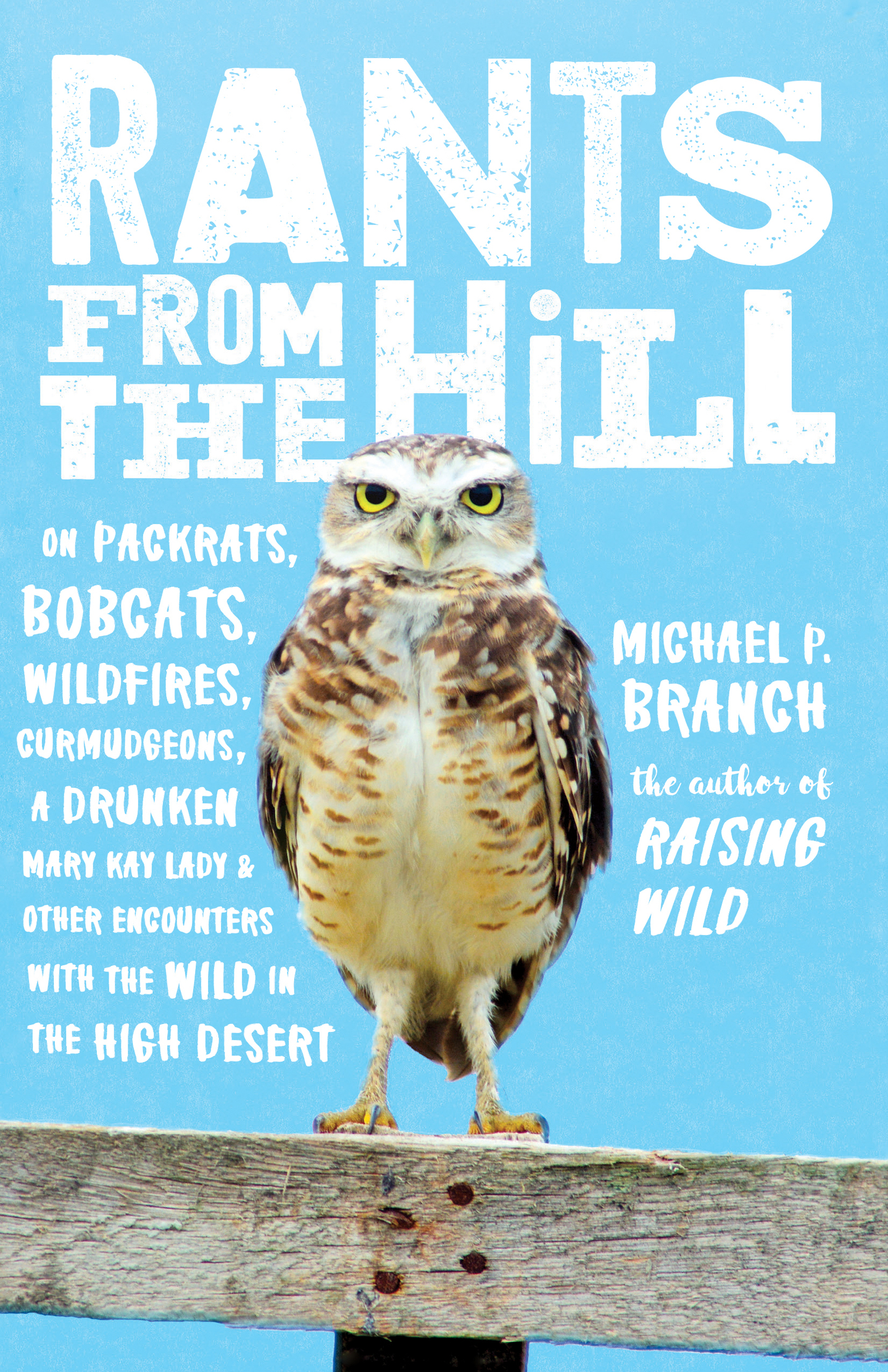

COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY EDSON HARDT / ISTOCK

COVER DESIGN BY DANIEL URBAN-BROWN

eBook design adapted from printed book design by Daniel Urban-Brown

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Branch, Michael P., author. | Branch, Michael P. Raising wild.

Title: Rants from the hill: on packrats, bobcats, wildfires, curmudgeons, a drunken Mary Kay lady, and other encounters with the wild in the high desert / Michael P. Branch.

Description: First edition. | Boulder: Roost Books, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016053828 | ISBN 9781611804577 (paperback: acid-free paper)

eISBN 9780834840911

Subjects: LCSH: Branch, Michael P.Homes and hauntsGreat Basin. | Wilderness areasGreat Basin. | DesertsGreat Basin. | Branch, Michael P.Family. | ParentingGreat Basin. | Natural historyGreat Basin. | Great BasinSocial life and customs. | NevadaSocial life and customs. | Great BasinDescription and travel. | NevadaDescription and travel. | BISAC: HUMOR / Form / Essays. | NATURE / Essays. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs.

Classification: LCC F789 .B74 2017 | DDC 979dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016053828

v4.1

a

For my parents, Stu and Sharon Branch

without you no hill

Benedictio: May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds. May your rivers flow without end, meandering through pastoral valleys tinkling with bells, past temples and castles and poets towers into a dark primeval forest where tigers belch and monkeys howl, through miasmal and mysterious swamps and down into a desert of red rock, blue mesas, domes and pinnacles and grottos of endless stone, and down again into a deep vast ancient unknown chasm where bars of sunlight blaze on profiled cliffs, where deer walk across the white sand beaches, where storms come and go as lightning clangs upon the high crags, where something strange and more beautiful and more full of wonder than your deepest dreams waits for youbeyond that next turning of the canyon walls.

E DWARD A BBEY , preface to the 1988

reprint of Desert Solitaire (1968)

CONTENTS

THE VIEW FROM RANTING HILL

I WAS NOT ALWAYS DEVOTED to the pastoral fantasy of living in the remote high desert of the American West. Earlier in life, I worked my way through the serial pastoral fantasies of withdrawing from the din and superficiality of overcivilization to a rustic life in the Blue Ridge Mountains, by the Atlantic seashore, and in a Florida swamp. But I like to think that I have become more focused over time, as I succumbed and committed to the driest and most impossible of pastoral fantasies more than twenty years ago: I am now a confirmed desert rat.

It might be said that all things pastoral are a form of fantasy, in the sense that our escapist dreams are our least achievable and most necessary. But there was something especially irrational about my passionate desire to retreat to a landscape as extreme and inhospitable as the one that became my home. The Great Basin is the largest of American deserts, a 190,000-square-mile immensity of alien territory that rolls out from the Rockies west to the Sierra Nevada, bordered on the north by the Columbia Plateau and down south by those better-known deserts, the Mojave and Sonoran. From this inconceivably vast desert basin no drop of water ever reaches the sea. Out here in northern Nevada, on the far western edge of the Great Basin, we live in the rain shadow of the Sierra, which limits our annual precipitation to about seven inches. Because the elevation is almost 6,000 feet it is cold here as well as hot, subject to blizzard as well as wildfire, and characterized by extremes of weather and temperature unmatched by any other US state.

While environmental writers often deploy the metaphor of falling in love to evoke a magical moment of intimacy with a natural landscape, the Great Basin Desert is so titanic, inhospitable, and unwelcoming that the urge to dwell here is not easily understood, even by those of us who have chosen to act on it. Given that pastoral fantasies remain perpetually vulnerable to threats as simple as bad weather or the need for a day job, my attempt at bucolic retreat in this land of wildfire, hypothermia, desiccation, and rattlers might seem ill-advised. But the sheer vastness and starkness of this place attracted me and then worked on me slowly, over time, like wind on rock, until I had no ambition greater than to make a life in these high, dry wilds.

Finding the way out here was a long, challenging process. Initially, my wife, Eryn, and I moved to a semirural area about fifteen miles northwest of Reno, Nevada. There we hiked, gardened, and played music but also worked, saved, and planned, always eyeing a move even farther into the hinterlands. After several years, we had saved enough to begin our search for a piece of raw land in a spectacular but isolated area of desert hills and canyons adjacent to public lands and at the foot of a stunning, split-summited, 8,000-foot mountain. Because it was so distant, high-elevation, fire-prone, and so frequently rendered inaccessible by snow, mud, and terrible roads, land in this area was relatively inexpensiveand because water is the name of the game here and only one well is permitted per parcel, large pieces of land were only marginally more expensive than smaller ones.

After a search that lasted several years, we purchased a hilly, 49.1-acre parcel near the end of an awful, 2.3-mile-long, nearly impassable dirt road. The land had no well, no building pad, and no access road, but it was wild, alluring, and very close to Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands stretching all the way to the foot of the Sierra Nevada in neighboring California. For several more years, as we saved up to build, we visited the property regularlyhiking, working to reduce fuels to prepare for wildfire, and considering where a house might someday be constructed. Before long, we cut a narrow, sinuous driveway, a half-mile-long strip of perilous caliche mud that wound to the top of a prominent hill at the back of the parcel. There, we later sunk a well and cleared a small patch of sagebrush and burned-over juniper snags in hopes of someday making a home. To help us visualize the house, I drove rebar stakes along the perimeter of the would-be structure and connected them with twine. We often trekked up to the site, opened camp chairs somewhere within the twine house, and imagined what it would be like to someday sit in that spot within our home, taking in that particular view of the distant, snowcapped mountains.