About Island Press

Since 1984, the nonprofit organization Island Press has been stimulating, shaping, and communicating ideas that are essential for solving environmental problems worldwide. With more than 1,000 titles in print and some 30 new releases each year, we are the nations leading publisher on environmental issues. We identify innovative thinkers and emerging trends in the environmental field. We work with world-renowned experts and authors to develop cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental challenges.

Island Press designs and executes educational campaigns in conjunction with our authors to communicate their critical messages in print, in person, and online using the latest technologies, innovative programs, and the media. Our goal is to reach targeted audiencesscientists, policymakers, environmental advocates, urban planners, the media, and concerned citizenswith information that can be used to create the framework for long-term ecological health and human well-being.

Island Press gratefully acknowledges major support of our work by The Agua Fund, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Bobolink Foundation, The Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation, Forrest C. and Frances H. Lattner Foundation, The JPB Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, The Oram Foundation, Inc., The Overbrook Foundation, The S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, The Summit Charitable Foundation, Inc., and many other generous supporters.

The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of our supporters.

Island Press mission is to provide the best ideas and information to those seeking to understand and protect the environment and create solutions to its complex problems. Join our newsletter to get the latest news on authors, events, and free book giveaways. Click here to join now!

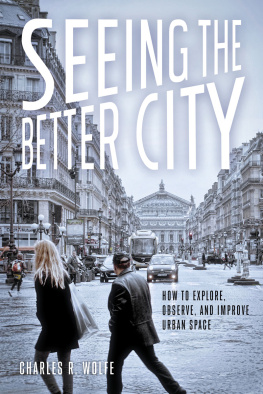

Copyright 2016 Charles R. Wolfe

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M St. NW, Suite 650, Washington, DC 20036

Island Press is a trademark of The Center for Resource Economics.

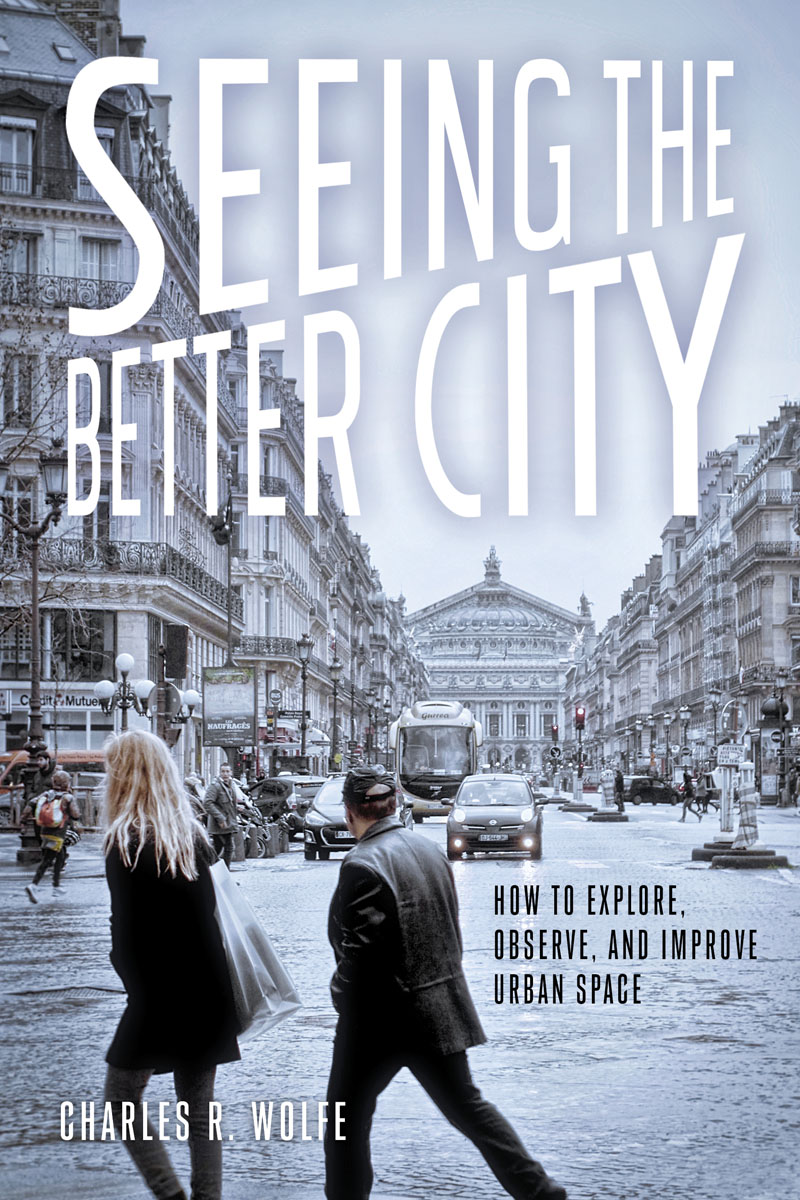

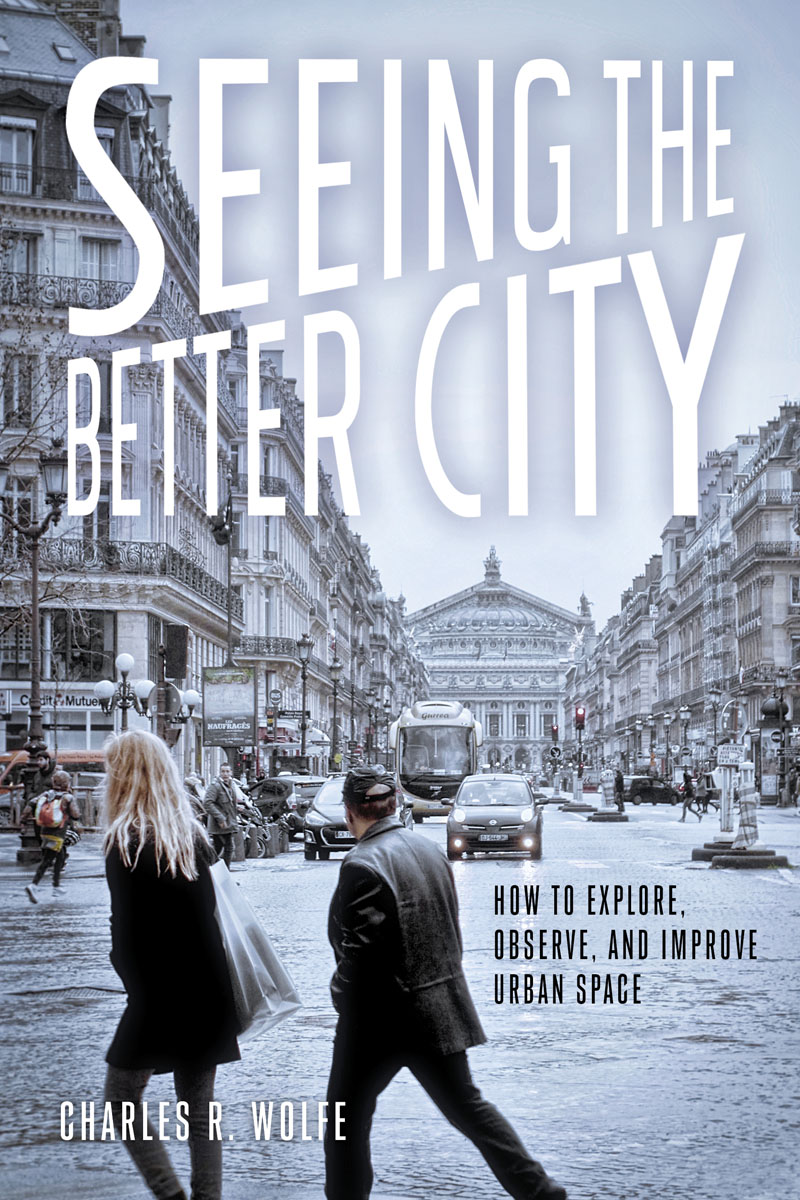

Cover image and interior images by Charles R. Wolfe, except where otherwise noted.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016946741

Printed on recycled, acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Keywords:

Adelaide, Albany, Austin, app, Berenice Abbott, community engagement, crowdsourcing, cultural geography, digital storytelling, exploration, flaneur, Iceland, Instagram, juxtaposition, Kevin Lynch, Madrona, Melbourne, Milan, Nice, observation, Paris, photography, Place des Vosges, Raleigh, Redmond, Rome, Seattle, Situationists, smart cities, smartphone, urbanism, Urbanism Without Effort, Vancouver, walkable, wayfinding

TO MY MOTHER, ROSAMOND WOLFE,

who is all about seeing the better details in life

CONTENTS

PREFACE

We mould [cities] in our images: they, in their turn, shape us by the resistance they offer when we try to impose our own personal form on them. In this sense, it seems that living in cities is an art, and we need the vocabulary of art, of style, to describe the peculiar relationship between man and material that exists in the continual, creative play of urban living. The city as we imagine it, the soft city of illusion, myth, aspiration, nightmare, is as real, maybe more real, than the hard city one can locate on maps, in statistics, in monographs on urban sociology and demography and architecture.

JONATHAN RABAN

Soft City

We all have within us the capacity to assess and communicate what we like and dislike about our surroundings, to respond with delight, sadness, fear, or anger, and to discover how best to improve the world around us. In particular, whatand howwe see defines the structure and context of our daily lives. As city dwellers, what we sense elicits emotional and intellectual responses about where we live or the places we visit that leave us wanting more after we return home. When crafting policy and regulations, and when making related political decisions, we need to do a better job of finding a role for our human experience.

This perspective comes from both my professional and personal experience. In the well-known essay A Way of Looking at Things, architect Peter Zumthor notes how childhood memories hold the deepest architectural experience the reservoir of architectural atmosphere and images that I explore in my work.urban imagery is an inherited trait. My father, Myer Wolfe, was the founder of the modern Department of Urban Design and Planning at the University of Washington, and was an early urban design theorist in the spirit of Kevin Lynch, Allan Jacobs, and others described here. Growing up, I learned to look at cities as holistic artifacts, or reflections, of the underlying forces at play in defining the stories behind urban form and neighborhoods. I learned how the facades of buildings, if not demolished or destroyed, inevitably show layers that are reflective of the sociocultural forces at play at each era of building and renovation.

But, as I have described in the book Urbanism Without Effort and various articles,

The perspectives I inherited from him included at least three other takeaways that have spurred me to write Seeing the Better City. First, a key purpose of using photographs to supplement the written word is to simulate a three-dimensional community as people perceive it. Second, peoples responses to these supplemental photographs may vary based on their cultural backgrounds and past social experiences. Finally, verbal communication alone is often insufficient to convey adequate information about urban space.

My motivation for writing this book and my desire to help people articulate what they seeboth what is working and what is ripe for improvement in their citiesis based on watching residents and pundits respond to various facets of urban change today. However, across space and time, the human response to change is remarkably universal. Consider the familiar sentiment in Charles Baudelaires description of the impact on the senses of Baron Haussmanns era of renewal in Paris that began in the mid-nineteenth century: As Paris changes, my melancholy deepens. The new palaces, covered by scaffolding and surrounded by blocks of stone, overlook the old suburbs that are being torn

Many would apply these sentiments to my hometown of Seattle, which is in the midst of tremendous, fast-paced transition and a great deal of debate about how to grow gracefully. Discussions about issues such as transportation, affordability, housing types, building heights, and density are at center stage. The physical appearance of some city neighborhoods is rapidly evolving and often looks very different from what existed less than a generation before.

Next page