__________

Teaching Aboriginal History at an Australian university brought me into unexpected contact with race politics in the United States. A disproportionate number of my students were from the USA, exchange students looking for something they could not study at their home universities. When asked what sparked their interest in the history of Aboriginal peoples experience of White Australia, these students were almost unanimous:

Ive studied race issues back home, from slavery to civil rights, and Id like to know how Black people have fared in Australia.

Well, I would respond, Aboriginal people here are indeed called Black, only theyre Indigenous. Their ancestors werent bought and sold in slave markets. They were dispossessed. Indians are Aboriginal peoples closest counterparts in the United States, not Black people.

With few exceptions, this reply would elicit surprise, or sometimes a polite indifference. Some students, by no means only African American ones, would respond: Maybe; but for me race is about colour. Thats what leads to discrimination. When you say colored in the United States, you generally mean Black. Thats why Im interested in the Aborigines. Theyre Black, too.

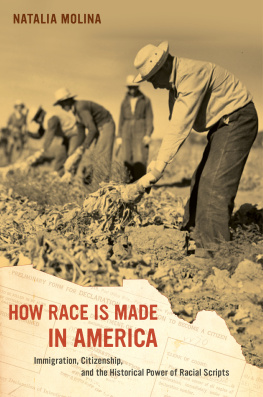

The few Aboriginal students tended not to reciprocate this sentiment. They generally took well to the US students, but without selecting for colour. They simply preferred them to the White Australians, whose innocence was all too familiar. Mention Native Americans, however, and the response of Aboriginal students was immediate and positive, as it was to the mention of Maoris, Palestinians, Sami, West Papuans or Native Hawaiians. In each case, Aboriginal students responded with a confidence they rarely displayed within the White university, a confidence that declared them to be speaking of their own. The community these students shared with other Indigenous people is deeper than colour, and more specific than discrimination. It is a common history: one of invasion, of loss of land, of elimination, of resistance, of survival and the hazards of renaissance. The role that colonialism has assigned to Indigenous people is to disappear. By contrast, though slavery meant the giving up of Africa, Black Americans were primarily colonised for their labour rather than for their land. These basic historical differences live on in settler popular culture, where representations of Black Australians and Red Americans distinctly resemble each other, while each contrasts sharply with representations of Black Americans. While Aboriginal people are called Black, for instance, they are not popularly credited with the natural sense of rhythm that still signifies fitness for labour on the part of those whose ancestors were enslaved. Conversely, unlike Aborigines, Black Americans have not been routinely stereotyped as a dying race. This convenient condition has instead been assigned to Native Americans.

Racialised distinctions such as these bespeak different histories, of different forms of expropriation in one case of labour, in another of land. Moreover, such differences are site-specific. Whereas the enslavement of Africans in the United States produced the most rigorously polarised regime of race, the enslavement of Africans in Brazil produced a variegated continuum of colour classifications. To recuperate the distinct histories that fall together under the common heading of race, this book will trace some of the ways in which regimes of race have reflected and reproduced different forms of colonialism. Race, I shall argue, is a trace of history: colonised populations continue to be racialised in specific ways that mark out and reproduce the unequal relationships into which Europeans have co-opted these populations. This argument will be exemplified with reference to the diversity distinguishing racial discourses obtaining in Australia, the USA, Brazil, central Europe, and Palestine/Israel.

The chapters to come will explore a range of racial constructs, each instantiating a particular colonial relationship: in Australia and in the USA, White authorities have generally accepted even targeted Indigenous peoples physical substance, synecdochically represented as blood, for assimilation into their own stock. When it has come to African American peoples physical substance, however, it has only been in the past few decades that US authorities have dispensed with the most rigorously exclusionary procedures for insulating the dominant stock, the one-drop rule having assigned a hyperpotency to African heredity that recalls the ineradicability of Jewishness in European antisemitism.of White immigration and officially sanctioned miscegenation intended to lighten the prevailing phenotype. Strategically, Brazils project of deracinating lower-order African Brazilians with a view to constructing a uniformly European nation resembles Israels project of deracinating lower-order Arab-Jews with a view to constructing a uniformly Jewish nation. In these last two cases, as we shall see, race works through de-racination.

There are no grounds for assuming that such striking disparities represent the uniform workings of a discursive monolith called race. Rather, this book will stress the diversity distinguishing the regimes of difference with which colonisers have sought to manage subject populations. These distinctions are very important. They entail different, and not always harmonious, strategies of anticolonial resistance. For instance, when Black people in the USA campaigned for equal rights in the mid-twentieth century, much of their political programme centred on the demand that they be treated equally with Whites. At the same time, however, treating Indians the same as Whites which is to say, assimilating them into mainstream society was a settler-colonial strategy that the Native American political movement, in common with the Aboriginal political movement in Australia, was striving to resist. The mathematics of the head-count is inimical to Native sovereignty. A focus on colour (or non-Whiteness) obscures such historically produced differences in this case, between a history of bodily exploitation and one of territorial dispossession. A relationship premised on the exploitation of enslaved labour requires the continual reproduction of its human providers. By contrast, a relationship premised on the evacuation of Native peoples territory requires that the peoples who originally occupied it should never be allowed back.