Warwick Anderson

VII

I

s my interest in the entwined histories of American tropical medicine and racial thought has endured now for most of my career, the intellectual debts that have accumulated are countless. Only the most pressing can be acknowledged here. Charles Rosenberg and Rosemary Stevens guided my first studies of colonial public health at the University of Pennsylvania. At Harvard, Allan Brandt, Arthur Kleinman, Evelynn Hammonds, and Mary Steedly helped me to reshape and develop many of my arguments. Colleagues in the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine at UCSF, and in the History Department at Berkeley-in particular, Adele Clarke, James Vernon, Philippe Bourgois, Vincanne Adams, Tom Laqueur, Sharon Kaufman, and Dorothy Porter-encouraged me to return to the book manuscript and provided inspiration and support. At Madison, I benefited greatly from the advice of colleagues in the Department of Medical History and Bioethics and at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Conversations with Judy Leavitt, Rick Keller, Mike Cullinane, Al McCoy, Courtney Johnson, Victor Bascara, and Maria Lepowsky proved especially valuable. Jean von Allmen, with characteristic efficiency, ensured I had time for writing.

s my interest in the entwined histories of American tropical medicine and racial thought has endured now for most of my career, the intellectual debts that have accumulated are countless. Only the most pressing can be acknowledged here. Charles Rosenberg and Rosemary Stevens guided my first studies of colonial public health at the University of Pennsylvania. At Harvard, Allan Brandt, Arthur Kleinman, Evelynn Hammonds, and Mary Steedly helped me to reshape and develop many of my arguments. Colleagues in the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine at UCSF, and in the History Department at Berkeley-in particular, Adele Clarke, James Vernon, Philippe Bourgois, Vincanne Adams, Tom Laqueur, Sharon Kaufman, and Dorothy Porter-encouraged me to return to the book manuscript and provided inspiration and support. At Madison, I benefited greatly from the advice of colleagues in the Department of Medical History and Bioethics and at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Conversations with Judy Leavitt, Rick Keller, Mike Cullinane, Al McCoy, Courtney Johnson, Victor Bascara, and Maria Lepowsky proved especially valuable. Jean von Allmen, with characteristic efficiency, ensured I had time for writing.

Bob Joy, Dan Doeppers, and Barbara Rosenkrantz read earlier versions of the book manuscript and peppered me with their questions, challenges, and doubts. I may not have responded adequately to all of their queries, but without their engagement the book would be the poorer. I was fortunate to have such generous and careful readers.

It was the enthusiasm and support of Vince Rafael that enabled me to complete this book. He and many other scholars of the Philippines, especially Michael Salman and Paul Kramer, have guided me through new territory and provided intellectual sustenance.

I would also like to thank Michelle Murphy, Jono Wearne, Matt Klugman, Martin Gibbs, Chris Shepherd, Peter Phipps, Dan Hamlin, and Kiko Benitez for research assistance. Kiko, too, read much of the manuscript and gave me helpful advice. Gabriela Soto Laveaga assisted with translation of some of the Spanish material and pointed me to Latin American analogies.

Without the enthusiasm and persistence of Ken Wissoker at Duke University Press, it is unlikely that I would ever have completed this book. Ken and Anitra Grisales have smoothed the path to publication and allayed most of the author's anxieties along the way.

This project was supported financially through a fellowship from the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies. I received travel grants from the Rockefeller Archive Center, the University of Pennsylvania, Harvard University, the Pacific Rim Research Program of the University of California, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

I am grateful for the assistance of archivists and librarians at the University of Pennsylvania, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, the Countway Medical Library and other Harvard libraries, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, the Library of Congress, the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine, the Bentley Library at the University of Michigan, the Bancroft Library at the University of California-Berkeley, the Kalmanowitz Library at UCSF, the Hagley Museum and Library, the Alan Mason Chesney Archives at Johns Hopkins University, the Wisconsin Historical Society Library, the Lbling Library of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Rockefeller Archive Center, the U.S. Army Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, the Massachusetts Archives, the Philippine National Archives, and the Rizal Library at Ateneo de Manila.

I have presented portions of this work at numerous institutions over the past fifteen years: through comment and discussion on these occasions, the book has emerged much improved. Sections of it have also benefited from the remarks of editors and anonymous reviewers for the following journals: Critical Inquiry, the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, the American Historical Review, Positions, and American Literary History.

Above all, I want to thank family and friends for gracefully putting up with my peculiar preoccupation with the history of colonial medicine -my own family, of course, but also the family of Ken and Rochelle Goldstein, who looked after me in Philadelphia. It is to the memory of Kenneth S. Goldstein that this book is dedicated.

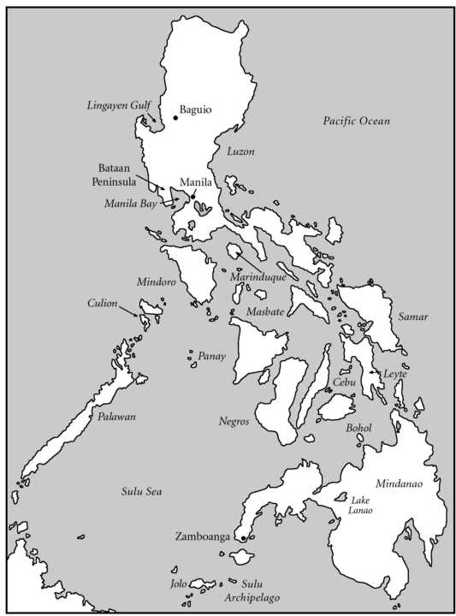

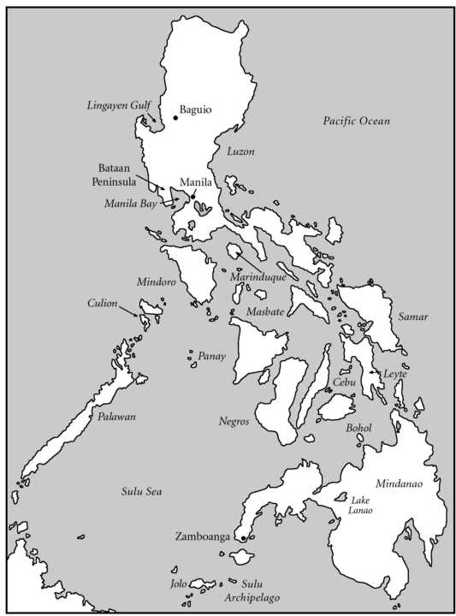

MAP I. Philippine archipelago.

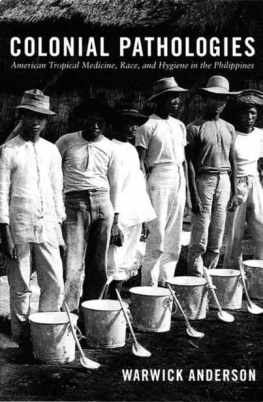

he only things that matter in this fallen world," Rudyard Kipling advised his friend W. Cameron Forbes in 1913, "are transportation and sanitation."' Forbes, the governor-general of the Philippines and a fastidious Harvard man, believed that the greater of these was sanitation. Indeed, since the defeat of Spanish forces in the archipelago in 1898, the American colonial authorities had eagerly taken up the burden of cleansing their newly acquired part of the Orient, attempting to purify not only its public spaces, water, and food, but also the bodies and conduct of the inhabitants. According to Victor G. Heiser, who was director of health in the Philippines from 1905 to 1915, it had to be understood that "the health of these people is the vital question of the Islands. To transform them from the weak and feeble race we have found them into the strong, healthy and enduring people that they may yet become is to lay the foundations for the successful future of the country."2 American military and civil health officers thus dedicated themselves to registering and refashioning Filipino bodies and social life, to forging an improved sanitary race out of the raw material found in the Philippine barrio. Hygiene reform in this particular fallen world was intrinsic to a "civilizing process," which was also an uneven and shallow process of Americanization.

he only things that matter in this fallen world," Rudyard Kipling advised his friend W. Cameron Forbes in 1913, "are transportation and sanitation."' Forbes, the governor-general of the Philippines and a fastidious Harvard man, believed that the greater of these was sanitation. Indeed, since the defeat of Spanish forces in the archipelago in 1898, the American colonial authorities had eagerly taken up the burden of cleansing their newly acquired part of the Orient, attempting to purify not only its public spaces, water, and food, but also the bodies and conduct of the inhabitants. According to Victor G. Heiser, who was director of health in the Philippines from 1905 to 1915, it had to be understood that "the health of these people is the vital question of the Islands. To transform them from the weak and feeble race we have found them into the strong, healthy and enduring people that they may yet become is to lay the foundations for the successful future of the country."2 American military and civil health officers thus dedicated themselves to registering and refashioning Filipino bodies and social life, to forging an improved sanitary race out of the raw material found in the Philippine barrio. Hygiene reform in this particular fallen world was intrinsic to a "civilizing process," which was also an uneven and shallow process of Americanization.

s my interest in the entwined histories of American tropical medicine and racial thought has endured now for most of my career, the intellectual debts that have accumulated are countless. Only the most pressing can be acknowledged here. Charles Rosenberg and Rosemary Stevens guided my first studies of colonial public health at the University of Pennsylvania. At Harvard, Allan Brandt, Arthur Kleinman, Evelynn Hammonds, and Mary Steedly helped me to reshape and develop many of my arguments. Colleagues in the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine at UCSF, and in the History Department at Berkeley-in particular, Adele Clarke, James Vernon, Philippe Bourgois, Vincanne Adams, Tom Laqueur, Sharon Kaufman, and Dorothy Porter-encouraged me to return to the book manuscript and provided inspiration and support. At Madison, I benefited greatly from the advice of colleagues in the Department of Medical History and Bioethics and at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Conversations with Judy Leavitt, Rick Keller, Mike Cullinane, Al McCoy, Courtney Johnson, Victor Bascara, and Maria Lepowsky proved especially valuable. Jean von Allmen, with characteristic efficiency, ensured I had time for writing.

s my interest in the entwined histories of American tropical medicine and racial thought has endured now for most of my career, the intellectual debts that have accumulated are countless. Only the most pressing can be acknowledged here. Charles Rosenberg and Rosemary Stevens guided my first studies of colonial public health at the University of Pennsylvania. At Harvard, Allan Brandt, Arthur Kleinman, Evelynn Hammonds, and Mary Steedly helped me to reshape and develop many of my arguments. Colleagues in the Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine at UCSF, and in the History Department at Berkeley-in particular, Adele Clarke, James Vernon, Philippe Bourgois, Vincanne Adams, Tom Laqueur, Sharon Kaufman, and Dorothy Porter-encouraged me to return to the book manuscript and provided inspiration and support. At Madison, I benefited greatly from the advice of colleagues in the Department of Medical History and Bioethics and at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Conversations with Judy Leavitt, Rick Keller, Mike Cullinane, Al McCoy, Courtney Johnson, Victor Bascara, and Maria Lepowsky proved especially valuable. Jean von Allmen, with characteristic efficiency, ensured I had time for writing.

he only things that matter in this fallen world," Rudyard Kipling advised his friend W. Cameron Forbes in 1913, "are transportation and sanitation."' Forbes, the governor-general of the Philippines and a fastidious Harvard man, believed that the greater of these was sanitation. Indeed, since the defeat of Spanish forces in the archipelago in 1898, the American colonial authorities had eagerly taken up the burden of cleansing their newly acquired part of the Orient, attempting to purify not only its public spaces, water, and food, but also the bodies and conduct of the inhabitants. According to Victor G. Heiser, who was director of health in the Philippines from 1905 to 1915, it had to be understood that "the health of these people is the vital question of the Islands. To transform them from the weak and feeble race we have found them into the strong, healthy and enduring people that they may yet become is to lay the foundations for the successful future of the country."2 American military and civil health officers thus dedicated themselves to registering and refashioning Filipino bodies and social life, to forging an improved sanitary race out of the raw material found in the Philippine barrio. Hygiene reform in this particular fallen world was intrinsic to a "civilizing process," which was also an uneven and shallow process of Americanization.

he only things that matter in this fallen world," Rudyard Kipling advised his friend W. Cameron Forbes in 1913, "are transportation and sanitation."' Forbes, the governor-general of the Philippines and a fastidious Harvard man, believed that the greater of these was sanitation. Indeed, since the defeat of Spanish forces in the archipelago in 1898, the American colonial authorities had eagerly taken up the burden of cleansing their newly acquired part of the Orient, attempting to purify not only its public spaces, water, and food, but also the bodies and conduct of the inhabitants. According to Victor G. Heiser, who was director of health in the Philippines from 1905 to 1915, it had to be understood that "the health of these people is the vital question of the Islands. To transform them from the weak and feeble race we have found them into the strong, healthy and enduring people that they may yet become is to lay the foundations for the successful future of the country."2 American military and civil health officers thus dedicated themselves to registering and refashioning Filipino bodies and social life, to forging an improved sanitary race out of the raw material found in the Philippine barrio. Hygiene reform in this particular fallen world was intrinsic to a "civilizing process," which was also an uneven and shallow process of Americanization.