This edition first published in paperback in the United States in 2014 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact ,

or write us at the above address

Copyright 2010, 2014 by Luis H. Francia

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-4683-1545-5

To Filipinos Everywhere

THE PHILIPPINES

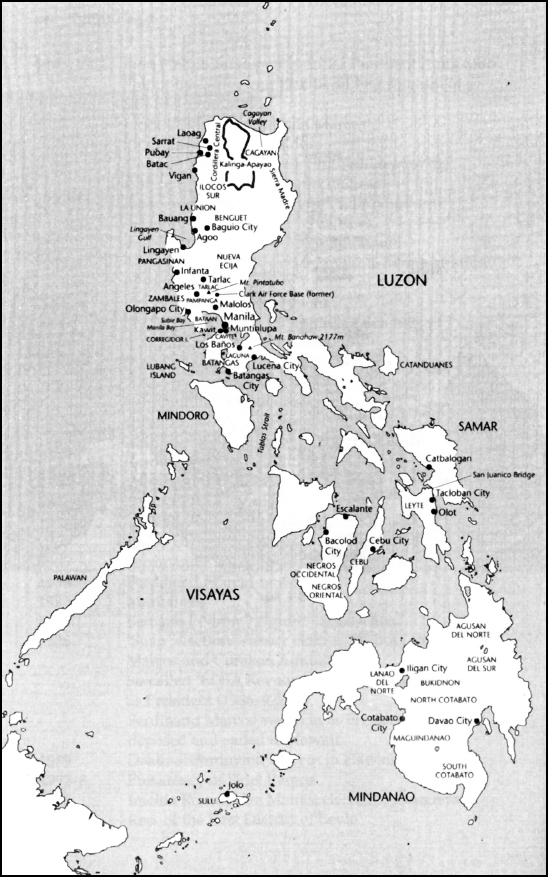

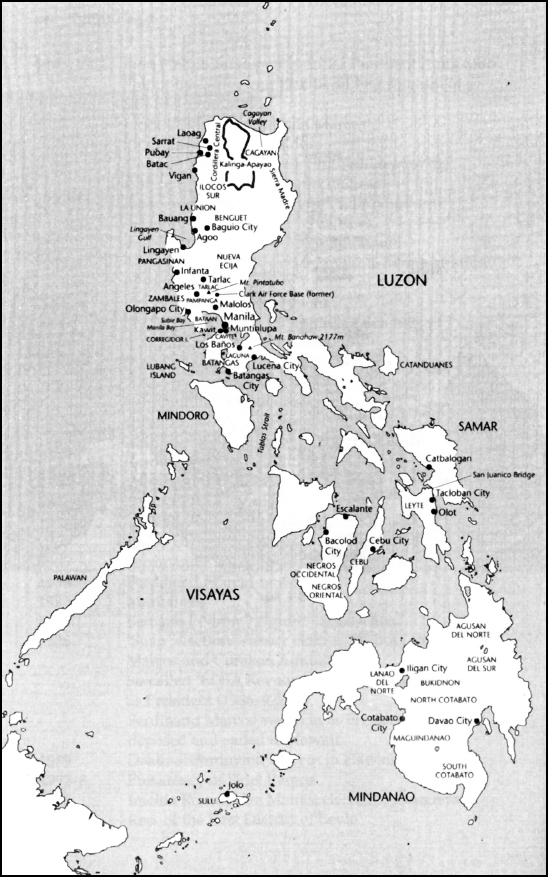

N O COUNTRY IS AN ISLAND, THOUGH THE COUNTRY THAT IS THE subject of this book, the Philippines, claims as its territory more than 7,000 islands. On the eastern edge of insular Southeast Asia, these islands stretch for more than 1,150 miles, bookended in the north by Taiwan and in the south by Indonesia and Brunei. The mighty Pacific Ocean interposes itself between the archipelago and North and South America on the other side of the globe, with Hawaii at roughly midpoint. To the west the South China Sea links the Philippines to continental Southeast Asian countries, among them Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand.

As a republic, it is barely more than six decades old, gaining emancipation from U.S. colonial rule in 1946, less than a year after Japan surrendered and brought the Pacific War to a halt. From 1946 to 1950, even as the United States and the Soviet Union were defining the world through the prism of the Cold War and their competing ideologies, the colonial order in Asia was disintegrating. India and Pakistan sprung into bloody being, twins separated at birth in 1947. Two years later, in 1949, the world took notice of yet another quarrelsome pair: Mao Tsetung and his Communist army, having defeated the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek, lay the foundation of the Peoples Republic of Chinaand indirectly, of the Republic of China in Taiwan, Chiang having fled across the straits in defeat. At the end of the same year, the Dutch recognized Indonesia as a sovereign nation.

Gaining independence, while exhilarating, was no panacea for a Southeast Asian archipelago that had continuously been occupied by a foreign power since 1565. Along with the metaphysical thrill, and challenge, of managing ones own destiny, one still had to pay bills (as well as pass them). There were hungry mouths to feed, an economy and infrastructure to build and rebuild, and institutions of governance to be either revamped or set up. The devastation wrought by World War II made recovery an excruciatingly difficult task. The fact that a triumphalist United States imposed certain inequitable conditions as a sine qua non of independence rendered establishing bona fide sovereignty an even harder challenge. What the great Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer, in his Child of All Nations, said bears repeating: As to defining what is colonial, isnt it just the conditions insisted upon by a victorious nation over the defeated nation so that the latter may give the victor sustenanceconditions that are made possible by the sharpness and might of weapons?

Nevertheless, the Philippine republic could now choose its own path. The odyssey to that point had been long and hard and violent. Though founded in 1898, the republic had seen its flowering delayed because of two wars: the Spanish-American War, which the United States won handily; and the subsequent 1899 Philippine-American War, when the revolutionary government under General Emilio Aguinaldo refused to accept its role as booty for the Americans. It was a brutal conflict that lasted a decade and resulted in U.S. occupation for half a century. And while 1946 signaled the birth of a nation, one of the first to take its place in the ranks of post-colonial states, the Philippines was indelibly marked by the DNA of colonialism. How could it be otherwise? Embedded and incarnated endlessly over the course of four hundred years, what and who had been strangers from foreign shoresto slightly alter Ronald Takakis memorable phrasehad metamorphosed into the familiar. The countrys very name encapsulates its colonial history. The Anglicized Philippines or the Spanish Filipinas is forever a reminder that this Southeast Asian archipelago was so named in 1543 by Ruy Lpez de Villalobos in honor of the sixteenth century Spanish crown prince who would in 1556 become King Felipe II.

There have been ill-fated attempts to toss out the Hispanic appellation and adopt a new one. The nineteenth-century revolutionary General Artemio Ricarte once proposed naming the country the Rizaline Islands, after its foremost national hero, Jos Rizal (with Filipinos henceforth to be known as Rizalinos). In 1978, during martial law, Ferdinand Marcos half-heartedly tried through the Batasan Pambansa, or National Assembly, to rename the nation Maharlika, a Tagalog word meaning nobilitypart of his skewed notion of aristocratic lineage and dressed-up history. (One foreign writer, eager to believe the exotic Orientalist bit fed to him by some clever jokers, wrote that it was a glorified term for the penis.) Neither name gained much traction; Filipinos of all ideological stripes, most of whom bore and continue to bear Hispanic names, were simply too used to the moniker to seriously consider changing it. Besides, whether one acknowledged it or not, by overstaying its welcome, Spain provoked the formation of a nationalist consciousness. Just as the name New York recalls its partly English provenance (replacing the Dutch Nieuw Amsterdam), so too does Las Islas Filipinas reflect the partly Hispanic roots of Filipino nationhood.

This book is a modest endeavor to introduce the reader with little or no knowledge of this Southeast Asian country to the realities that have marked the journey of becoming Filipino, from pre-colonial times to the first decade of the second millennium. No attempt at a definitive history is being made here; a mission impossible, at any rate. And let me be the first to acknowledge that this is an incomplete history, as every history must be. Significant new archaeological finds may and will probably be made; new interpretations will be offered, as well they should be. For what is past never stays put and lives on in us; it is, according to the late Filipino historian Renato Constantino, a continuing past, illuminating the present just as surely as light from a distant star. Nevertheless I believe that this book summarizes clearly and concisely the different forces that have, for better or worse, transformed an archipelago into a republic, and imparted to its inhabitants a notion, however imperfect, of a nation.

Who were the Indios Bravos? Brilliant nineteenth-century polymath, doctor, bon vivant, and writer Jos Rizal and his friends gave themselves the name, half in jest and half in all seriousness, after having watched a Wild West show in Paris in 1889. Indio, of course, was the disparaging term the Spanish used for the indigenous populations in their colonies. Rizal and these other expatriate ilustrados, or the enlightened ones, as they were referred to, admired both the excellent horsemanship and the dignity of the Native American performersand recognized in them kindred spirits. They were indeed brave Indians, their peculiar status in the world mirroring somewhat that of the Filipinos themselves, who were highly critical of the Spanish colonial regime in Manila and who in Madrid and Barcelona advocated far-reaching reforms at the same time that they professed loyalty to Mother Spain. By appropriating the term meant to put them in their place, Los Indios Bravos were signaling the Spanish their intent to take charge of their own destiny. It was a highly symbolic act, representing a paradigmatic shift in the burgeoning nationalist consciousness.