Contents

Page List

Guide

WARand

RESISTANCE

in the

PHILIPPINES, 19421944

WARand

RESISTANCE

in the

PHILIPPINES, 19421944

JAMES KELLY MORNINGSTAR

Naval Institute Press

Annapolis, Maryland

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2021 by James Morningstar

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Morningstar, James Kelly, author.

Title: War and resistance in the Philippines, 19421944 / James Kelly Morningstar.

Description: Annapolis, Maryland : Naval Institute Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020050510 (print) | LCCN 2020050511 (ebook) | ISBN 9781682475690 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781682476291 (ebook) | ISBN 9781682476291 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 19391945Underground movementsPhilippines. | GuerrillasPhilippines. | PhilippinesHistoryJapanese occupation, 19421945.

Classification: LCC D802.P5 M67 2021 (print) | LCC D802.P5 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/599dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020050510

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020050511

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

Printed in the United States of America.

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 219 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

Maps drawn by Chris Robinson.

To Jon Tetsuro Sumida The last great gentleman among military historians

Contents

Maps

Preface

I n the two-and-a-half years between the Japanese conquest of the Philippines in 1942 and Gen. Douglas MacArthurs return in October 1944, some 260,000 guerrillas in the Philippines waged an epic campaign against imperial subjugation. Their fight inspired resistance by the general population on a national level, obstructed Japanese efforts to economically exploit the islands, and set the conditions for eventual liberation by U.S. forces. Their campaign gave critical weight to MacArthurs argument for returning to the Philippines and thereby altered the course of the Pacific War. Moreover, the guerrillas struggle for power significantly defined the social and political aspects of the postwar Philippine nation. Their story, however, has never been fully told. There is no comprehensive official or scholarly account or assessment of their struggle. As a result, evaluations of the geographic, cultural, social, political, and economic dynamics of the war remain incomplete.

Drawing from considerable though narrowly focused literature, memoirs, and archival material, reinforced with a multidisciplinary academic approach, this book is an attempt to fill this historiographical void by providing a comprehensive narrative of the military and nonmilitary interactions between the Japanese, the Americans, andabove allthe Filipinos during the period of occupation. No one work, of course, can hope to capture the entirety of such an epic story. Rather, it is the intention of this book to provide a basis for a fuller discussion of resistance during war as experienced in the Philippines during World War II. As such, it is necessary to first provide historical context to the war.

1

Introduction

Three Roads to War

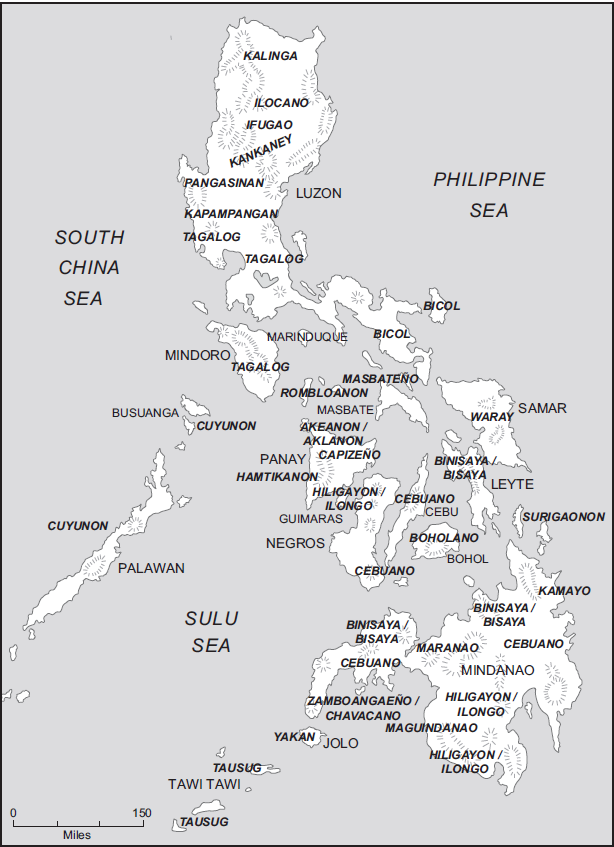

I n many ways, World War II in the Philippines was the culmination of imperial conflict dating back to 1541 when a Spanish adventurer arbitrarily grouped 7,100 Southwest Pacific islands, with more than one hundred diverse tribes, and named them in honor of his king (see

Generations of Filipino elites sent their children to European universities, and by the early nineteenth century they brought back radical democratic notions that climaxed with the failed Katipunan revolution of 189697. The American victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898, however, quickly rekindled Filipino hopes for independence. The U.S. Navy returned the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo from exile in Hong Kong to help secure the islands. Believing other powersparticularly Japanwere waiting to pounce, President William McKinley decided to retain the Philippines as a protectorate until they could govern and defend themselves. Aguinaldo felt betrayed by this decision and led a new insurrection that lasted until his defeat in 1902 at the hands of the Americans and their Filipino allies.

MAP 1.1 The Philippine Islands and major ethnic groups

As McKinley suspected, U.S. control of the Philippines thwarted Japans imperialist ambitions. In 1893 the Overseas Development Society in Tokyo delineated the empires regional interests: Men in the north, materials in the south.

With domestic resources plentiful and population growth manageable in the Philippines, the Americans proved to be disinterested imperialists. They opted not to adequately invest in defenses for the Philippines, which U.S. military experts deemed fundamentally indefensible anyway. They pursued a native attraction policy thatdespite its notable racismseemed to placate most Filipinos with improved government, education, hospitals, sanitation, and other reforms. This policy, however, did little to curb rising social antagonisms between Filipino underclasses and elites.

U.S.-guaranteed rights moved the Philippine class struggle into a new phase. Newly legal workers and peasants unions and political parties attracted international attention. In 1922 American communist William Janequette (alias Harrison George) invited labor leaders Jacinto Manahan, Domingo Ponce, and Crisanto Evangelista to the first congress of the Oriental Transportation Workers in Canton, China.

The rising Philippine political movements pushed the United States to honor its pledge to grant independence. In 1935 Congress responded with the Tydings-McDuffie Act that promised Philippine independence after a ten-year period intended to allow for the organization of a new government and military defenses. When Manuel Quezon became the countrys first president, Franklin Roosevelt warned him that the American military force in the Islands is too small to protect the Philippines against foreign invasion, and he deemed it impossible to induce Congress to appropriate the necessary funds for the military defense of the Islands and the maintenance of an army of sufficient size to keep any enemy at bay. Roosevelt granted Quezons request to send his old friend Gen. Douglas MacArthur to be his military advisor and serve as the islands first field marshal.

At the same time, the Tydings-McDuffie Act irritated Tokyo. Japan had recently invested millions of pesos both to build corporations in the Philippines and to help 775 Japanese-owned small stores in the islands compete with 13,818 rival Chinese shops. Moreover, the United States was setting a precedent by being the first imperial nation to voluntarily free a colony. This not only undermined imperial systems, it also threatened Japans interests by creating a new nationalistic Philippine government bent on restricting immigration and foreign economic exploitation. When Japan invaded China in 1937, it warily noted a protest boycott of Japanese products initiated by the Chinese community in the Philippines that monopolized 80 percent of the countrys retail.

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992