Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2012 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford, OX1 2EW

Copyright 2012 Nathan N. Prefer

ISBN 978-1-61200-155-5

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-156-2

ISBN 9781612001562 (epub)

ISBN 9781612001562 (prc)

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and

the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

E-mail:

CONTENTS

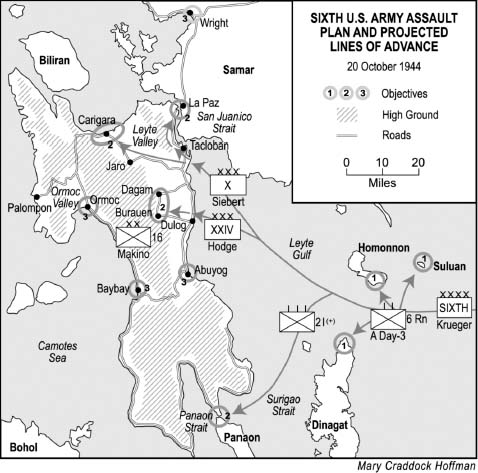

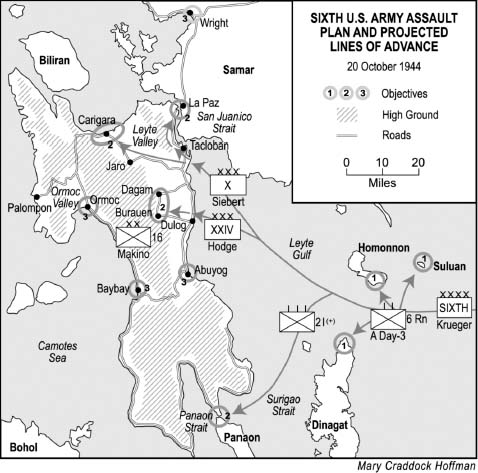

MAPS

All maps created by Mary Craddock Hoffman / STYLOGRAPHIX

To the men and women of all nations who fought, suffered, bled and died on the island of Leyte, and so many other islands and places around the world few had ever heard of before, being thrust into the ongoing battle for freedom.

The Leyte Operation made inordinate demands upon the troops. It is impossible for me to depict the hardships they had to endure or the desperate resistance they had to overcome. Our troop units included numerous battle-wise veterans, but also many others who received their first baptism of fire on the beaches or in the flooded rice fields or mountain fastnesses of the island. Veterans and recruits alike demonstrated outstanding valor and determination and proved the American Soldier superior to the soldier of Nippon.

General Walter Krueger,

Commanding, Sixth U.S. Army

in From Down Under to Nippon:

The Story of Sixth Army in World War II

1963. P. 187

When [General Walter] Krueger found an infantryman with untreated blisters, athlete's foot, or leaky socks, the soldier's noncoms lost their stripes and his officers got official reprimands. We in the lower echelons sort of loved the crusty old boy, were delighted to learn that he had enlisted as a private and risen through the ranks, and were not surprised when later he turned out to be one of the most distinguished generals in the pacific.

Bill Mauldin, The Brass Ring (1971)

I love the infantry because they are the underdogs. They are the mud-rain-and-wind boys. They have no comforts, and they even learn to live without the necessities. And in the end they are the guys that wars can't be won without.

Ernie Pyle, New York World Telegram (May 5, 1943)

The system was popularly called leapfrogging, and hailed as something new in warfare. But it was actually the adaptation of modern instrumentalities of war to a concept as ancient as war itself. Derived from the classic strategy of envelopment, it was given a new name, imposed by modern conditions. Never before had a field of battle embraced land and water in such relative proportions. Earlier campaigns had been decided on either land or sea. However, the process of transferring troops by sea as well as by land appeared to conceal the fact that the system was merely that of envelopment applied to a new type of battle area. It has always proved the ideal method for success by inferior but faster-moving forces.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (1964)

INTRODUCTION

T he story of the U.S. Army's battle for Leyte Island in late 1944January 1945 numbers among many tales of many battles fought by that army during the global Second World War. But is it just another battle? To military historians who have studied the war in the Pacific, the answer has been lost in the more flamboyant tales of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which the Battle for Leyte precipitated. In that naval battle, which sealed the fate of Imperial Japan's naval power for the war's duration, the chance for Japan to regain the naval initiative was forever destroyed, as was the fleet Japan sent to contest the American landings on Leyte. With the destruction and retreat of the enemy fleet remnants, the Battle for Leyte was assumed by many to have been won. The decisive battle that Japanese naval leaders had long sought had gone against them, and there now remained only the need to continue moving closer to the home islands of Japan to end the war.

But there was another decisive battle at Leyte, largely overlooked. Although in the years since the war more than a dozen books and monographs have appeared that detail various aspects of the naval Battle of Leyte Gulf, not one non-official work details the army's struggle for Leyte. Again, it appears that the assumption has been that since the naval battle was so clearly successful that the land campaign was simply a pro forma matter, with no unusual or atypical events to make it noticeable and stand out among many similar battles. But was that the case?

It was not. The Leyte Campaign, one of the largest combined operations of the Pacific War, quickly turned into one of the most difficult and deadly ground campaigns of the Southwest Pacific Theater. A full American army, with two corps and more than seven American divisions under it's command in the middle of the campaign, devoted itself for four months to subduing the Japanese defenders of Leyte. If the naval Battle of Leyte Gulf was the decisive naval engagement of the second half of the war, then the land battle for Leyte was the decisive ground forces battle as well. For the Japanese decided to make it so.

The land campaign for Leyte involved more than two hundred thousand American soldiers, far more than the number of sailors and Marines who fought the three-day Battle of Leyte Gulf. These soldiers, many of whom spent the entire four months deep in heavy jungles, fighting in spite of typhoons and the rainy season, basically destroyed the fabric of the planned Japanese defense of the entire Philippines. For the Japanese High Command had decided, albeit late, that rather than fight the decisive battle for the Philippines on Luzon, it would be fought on Leyte. That decision alone made the Leyte Campaign decisive, but when the Japanese poured in their best troops from China, Korea, Japan and other Philippine islands, they also committed their best chance of holding the Philippines and keeping open their essential supply lines to the Southeast Asian natural resources upon which their war effort depended.

Nor did the Leyte Campaign go as planned. Few battles ever did, but the Leyte Campaign was full of surprises. Initially only one Japanese division defended the island, and the four American divisions should have been more than enough to overwhelm the defenders. But the change in Japanese policy changed everything. Before the battle was over another three American divisions had to be committed, another division-sized amphibious landing conducted, and plans and preparations for future assaults changed, delayed, postponed. And the cream of the Imperial Japanese Army died on Leyte. At least two of the reinforcing divisions were rated as among the best in the Imperial Japanese Army in 1944, and the bulk of these divisions were destroyed on Leyte. Japanese air power, husbanded for the defense of the Philippines, was also largely destroyed during the campaign, making the rest of the Philippine battles less deadly then they would otherwise have been. Indeed, the Battle for Luzon, on the main Philippine island, can be said to have been won with the Battle of Leyte, during which Japanese air and naval power was rendered ineffective and the best of the Japanese soldiers destroyed, rather than building stronger defenses on Luzon.

Next page