A WAR OF FRONTIER AND EMPIRE

T HE P HILIPPINE -A MERICAN W AR , 18991902

DAVID J. SILBEY

H ILL AND W ANG

A DIVISION OF FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX

NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Mari

Introduction: The Urgency of the Asking

For Americans, it was a war of frontier, and of empire. It was a war that brought together the dominant American experience of the nineteenth century, the chaotic and defining expansion westward, with a new and at times uncomfortable imperial ambition. Manifest destiny, though still powerful, seemed less manifest and more ambiguous; less fate than one path among many. Americans had come to feel that the continent was perhaps too small to contain them and their nation. But what form was American entry into global power to take? The war did not provide an answer, but it did confirm the urgency of the asking.

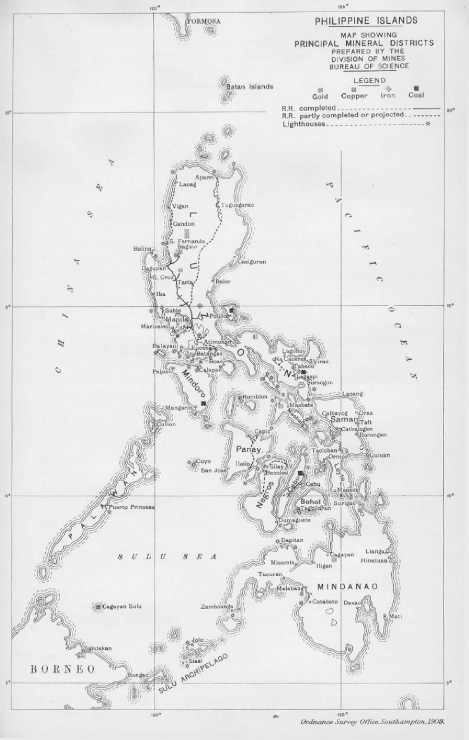

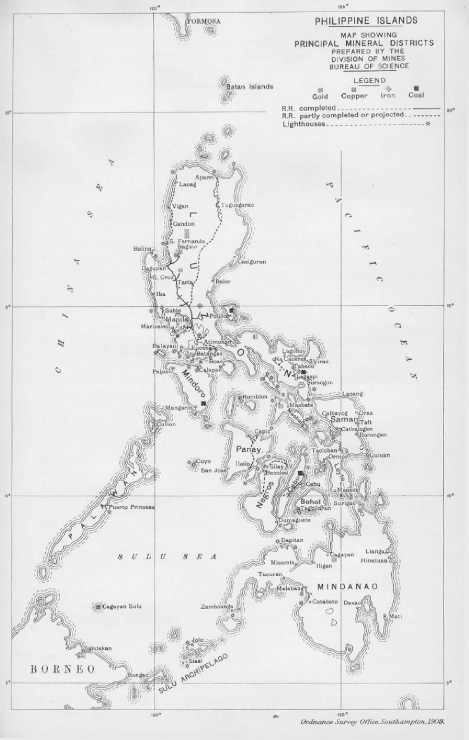

That energetic American nationalism would have been unfamiliar to most Filipinos. In fact, to label the inhabitants of the Philippines as Filipinos in 1899 would be to use a misnomer. Few Filipinos felt an overarching sense of the archipelago as a single united nation. Ordinary loyalties to region, to patron, or to family were much more likely. The war they fought was, in many ways, a war of those loyalties. Thus, while the Western powers fighting for dominance in the Philippine ArchipelagoSpain and the United Stateswere relatively unitary actors, the forces resisting them were not. There was, despite the later assumption of both Filipino historians and postVietnam War American historians, no Philippine nation. There was no single central conception of state and nation that animated those fighting (or not fighting) against their colonial powers. There was, instead, a shaky coalition of groups that resisted. These groups were fundamentally different in their strategies and tactics, and the attention they paid to the titular leader of the revolution, Emilio Aguinaldo, varied greatly, even before his capture in 1901. They were made up of different ethnic groups, speaking different languages, and fighting in different ways.

But a peculiar thing happened. The Philippine-American War became, as seen dimly in retrospect, a war of national striving. At the time it was not a revolutionary war, in the same pungent and independent sense that Americans think of their revolution. But in the decades afterward the war became that kind of conflict, held up as the first unified Filipino experience of the modern era. Many had fought and almost everyone had experienced the war. Because of that, it gained status as a first struggle for independence and national pride. To understand the Filipino-American War, a Philippine historian said, is to understand a large part of the groundwork of contemporary Philippine society.

This retroactive reordering sometimes has odd effects. For example, what should we call the conflict? War? Revolution? Insurgency? All of those labels have been applied, and all have been disputed. Who was the United States fighting? The Philippines? Filipinos? A Tagalog insurgency? These too have all been suggested and criticized.

Could the conflict even be called a war? By the standards of the day, sovereignty had passed legitimately from the Spanish to the Americans, the Philippines had not been an independent nation for centuries before that, and the inhabitants of the Philippines did not conceive of themselves as part of a single unified social, political, and cultural body. If there was no Philippine nation to engage in war or be conquered, then would not labeling the fight a war be a grave misrepresentation? In such an analysis what happened in the archipelago from 1899 to 1902 was an insurgency, not a war.

Filipino historians starting in the 1950s saw the conflict as one of a nascent nation coming into its own, cruelly subjugated first by the Spanish and then by the United States. They explicitly denied such an interpretation. This Filipino nation had become unified under the lash of war, and had foughtif unsuccessfullyagainst its conquerors. The war was a war. To reduce it to an insurgency, these historians believed, was to betray that nation, and was to take part in a larger effort to subjugate the Filipinos and their past. Filipino history, Renato Constantino wrote, had been used to capture [Filipino] minds and make them believe that their conquerors were really altruistic and self-abnegating partners.

How, then, should we refer to it? There are arguments of merit on both sides of the question, andas frustratingly usual in historyarriving at a definitive conclusion is difficult. Brian Linn, for one, simply avoids the issue by referring to the conflict as the War in the Philippines. But perhaps we can place a layer of sophistication over the issue. At the time of the conflict, the Philippine nation was barely formed. Tagalogs, Moros, and the other Filipino tribal groups did not connect themselves to each other in a single, imagined community. Local loyaltieswhether tribal or client/patronremained more powerful than national ones. This certainly changed during the war, and, at its height, it could be argued than the Philippines was closer to sociocultural unity than at any time before. But the islands ruled by the United States after 1902 were still only a single unit in an administrative sense. Having said that, however, the legal argument that sovereignty passed without interruption from the Spanish to the Americans should be treated with some skepticism. By the standards of the day, the handover from Spain to the United States was indeed transacted according to law and custom. But any number of treaties during this periodthe 1885 Treaty of Berlin to name but one examplelegally handed over the rule of captive peoples to one Western power or another. That such handovers gave anyone, American or otherwise, anything but the most formal sort of sovereignty is open to question. Moral suasion did not come hand in hand with dominance.

While the conflict at the time was hardly a war between two sovereign nations, for Filipinos, that struggle became the central event of their national myth. They reimposed the idea of a nation onto the warring tribes of 18991902, and traced the birth of the idea of a larger Filipino nation to those years. Though there was no Filipino nation in the conflict, the Filipino nation could not have existed without the war. To label it an insurgency ignores that foundational importance.

Finally, there is the quiet misgiving that comes from refusing to call a conflict what the people most intimately affected by it would prefer. Too much of Philippine history has been organized and conceptually framed from an outsiders perspective. A series of imperial mastersSpanish, American, and Japanesehave ruled the Philippines and ruled histories of the archipelago. Even the names of the historical erasLater Spanish Colonialism, American Colonialism, the Japanese Occupationreflect this. When it comes down to it, the conflict was fought in the islands, Filipinos fought and died (on both sides) in it, and they may well have earned the right to call it what they wish. Unless we are willing to call the North American period from 1776 to 1783 the Colonial Insurgency, perhaps we should honor that wish. Thus, while understanding all the caveats, complaints, hedges, and ambiguities connected with it, I shall nonetheless refer to the conflict of 1899 1902 as the Philippine-American War.