Contents

Page List

POST-COLONIAL NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE PHILIPPINES

This book is for Clive and Isabel Weekley and dedicated to the loving memory of Alexis, Jannette and Peter Bankoff

Post-Colonial National Identity in the Philippines

Celebrating the centennial of independence

GREG BANKOFF

University of Auckland, New Zealand

KATHLEEN WEEKLEY

Swinburne University of Technology, Australia

First published 2002 by Ashgate Publishing

Reissued 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Greg Bankoff and Katherine Weekley 2002

The authors have asserted their moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 2002102827

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-73090-8 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-18810-2 (ebk)

Contents

No man or woman is an island and no book can be solely attributed to its authors. This study is no different and owes much to the generosity and patience of many. In particular, we are grateful for the funding made available through the Small Grants scheme of Swinburne University of Technology that enabled Kathleen to visit the Philippines in 1999, and to the Auckland University Research Committee grants that provided Greg with the wherewithal to go there in 1998 and 1999. Special thanks, too, to Norman Long and Thea Hilhorst of the Centre for Rural Development Sociology at Wageningen Agricultural University in the Netherlands for making possible a four month fellowship for Greg in 1998/99 during which some of the work on this book was completed.

Our gratitude extends to the staff both academic and administrative of our respective institutions. Academic leadership and understanding colleagues in the History Department have made the years working at the University of Auckland productive ones, while the Institute for Social Research, Swinburne University, has provided constant support in every dimension of working life, including the creation of the all-important but all too rare happy workplace. Many colleagues and comrades in the Philippines have also provided the usual abundance of friendship, logistical help and intellectual stimulation: warm thanks especially to Neri Colmenares, Shally Vitan, Joel Rocamora, Francisco Nemenzo, Nathan Quimpo, Arnold Azurin and Butch Dalisay.

From Kathleen, much gratitude goes to Alastair Davidson for his friendship and unstinting support, and comments on draft chapters. From Greg, a similar appreciation extends to Esther Velthoen, who is as about as familiar with some of these chapters as he is. Many thanks to both.

Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to David Hudson for his keen-eyed editing work; to Geraldine Suter for the index; and to Cesar Lacanienta and his staff at the photo-duplication service of the Rizal Library of Ateneo de Manila University for their help and patience over the years.

The origins of this book date from the 1998 Philippine Studies Association of Australia conference held in Townsville, Australia, on 911 July, at which the authors discovered they were both working on similar studies. Rather than compete, they decided to collaborate. What follows is the fruitful outcome of that decision. The authors would like to thank the organisers of that event for the unwitting part they played in bringing two previous strangers together. Of course, the authors alone are responsible for the ideas and opinions expressed here; they are still talking to each other after what was, for both, a first experience at co-authoring, which is encouraging and, we hope, bodes well for the book.

G.B.

K. W.

Authors Note

Sections of have appeared in respectively Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde (157, 3, 2001, pp. 21-42) and Public Policy (2, 4, 1998, pp. 28-58).

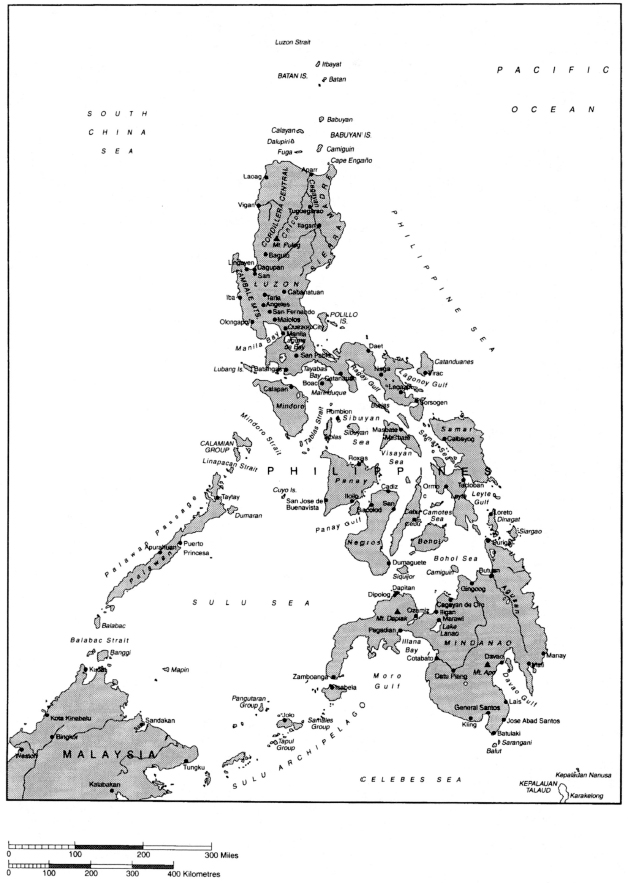

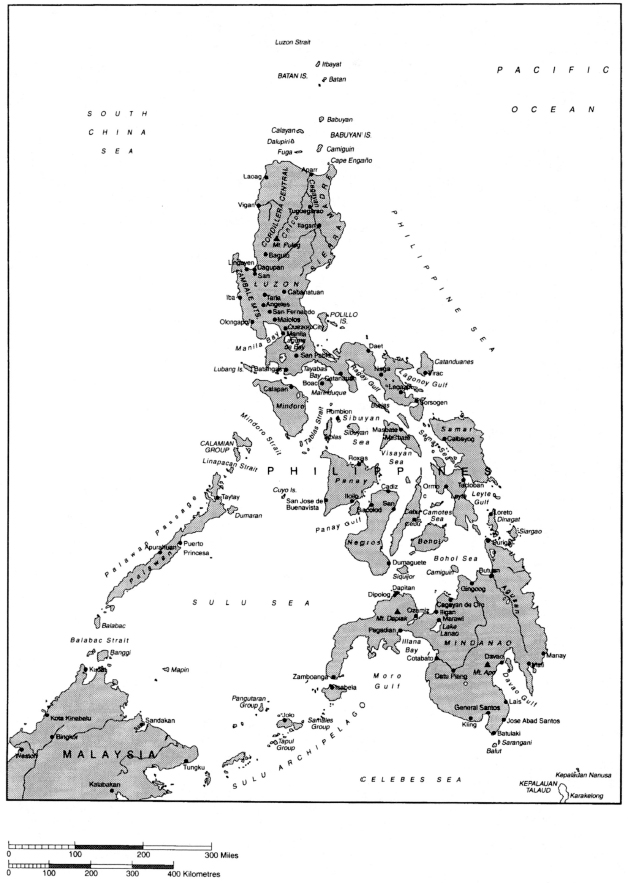

Map of the Philippines

The Philippines celebrated the centennial of its birth as a nation on 12 June 1998. In temperatures that soared into the mid 30s centigrade, huge crowds gathered in central Manila to watch a parade of floats commemorating the historic moment when General Emilio Aguinaldo issued a proclamation declaring his country independent after 333 years of Spanish colonialism. As the events surrounding that occasion were re-enacted in front of President Fidel Ramos, he was symbolically handed the national flag to wave in the place of his illustrious predecessor. No other gesture could so clearly identify him in the publics eye as the generals direct heir and leader of a sovereign state. But the centennial was much more than a celebration of that single act. It was a series of anniversaries commemorating the significant stages in a popular revolution that engulfed the Philippines archipelago between the open declaration of liberty made at Pugad Lawin in 1896 and the adoption of Asias first republican constitution at Malolos in 1899.

However, historical interpretations are rarely as simple or straight-forward as that. Even the dates to be commemorated are often a matter of dispute. Accordingly, the Philippines has declared its independence at least three times in its history: from the Spanish on 12 June 1898, under Japanese tutelage on 14 October 1943, and by American fiat on 4 July 1946.

The notion of an unfinished revolution dominates the subsequent discussion of the twentieth century, casting its shadow over historical interpretations of the later Commonwealth governments and the early post-war presidencies of Manuel Roxas, Elpidio Quirino, Ramon Magsaysay, Carlos Garcia and Diosdado Macapagal. Under the martial law that heralded the birth of the New Society (Bagong Lipunan) of President Ferdinand Marcos in the 1970s, an attempt was made to reshape Filipino society along quasi-corporatist lines. Congress was padlocked, the media muzzled, universities closed down and many constitutional rights suspended, while Filipinos were urged to be more self-reliant, self-disciplined and self-sufficient. The military and private militias took care of any who doubted the regimes efficacy or called into question the presidents personal probity. Armed dissent, which in the form of the Huk rebellion in Central Luzon had been contained in the immediate post-war years, now became more widespread as both the New Peoples Army (NPA) of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and the Bangsa Moro Army of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and their subsequent splinter organisations waged a relentless war of attrition on the centralised state. The People Power or EDSA Revolution which finally toppled the dictatorship in 1986 raised high expectations of radical reform that went largely unfulfilled under the restored constitutional governments of Corazon Aquino, Fidel Ramos and Joseph Estrada. Little has really changed in the nature of Filipino society or those who control it over the past century.