Also by Denis Hayes

Rays of Hope: The Transition to a Post-Petroleum World

The Official Earth Day Guide to Planet Repair

Pollution: The Neglected Dimensions

Repairs, Reuse, Recycling: First Steps Toward a Sustainable Society

Also by Gail Boyer Hayes

Pulmonary Hypertension: A Patients Survival Guide

Solar Access Law

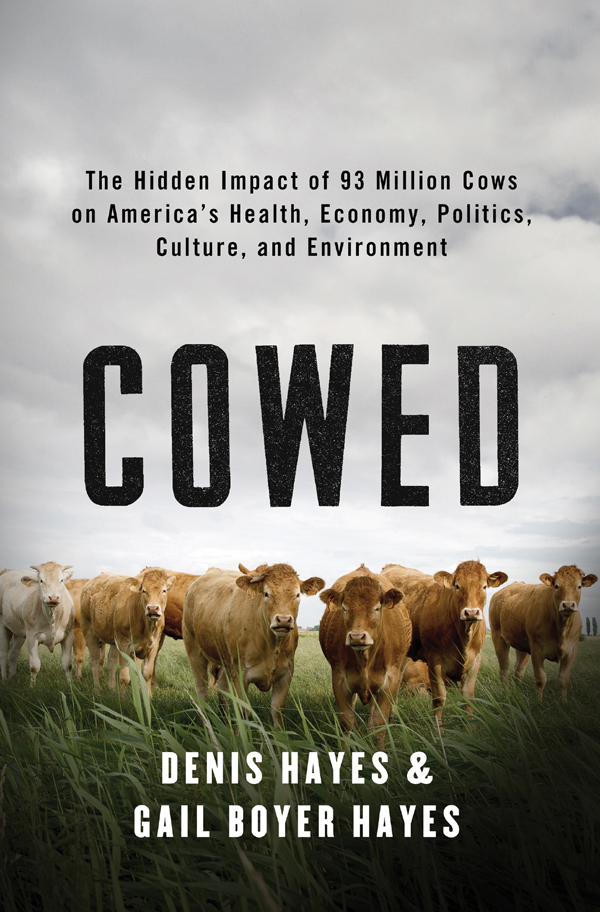

COWED

The Hidden Impact of

93 Million Cows on Americas Health,

Economy, Politics, Culture, and Environment

Denis Hayes & Gail Boyer Hayes

Copyright 2015 by Denis Hayes and Gail Boyer Hayes

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Kristen Bearse

Production manager: Anna Oler

ISBN 978-0-393-23994-2

ISBN 978-0-393-24663-6 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For our daughter, Lisa, our granddaughter, Sheridan,... and for cows.

COWED

Cows shaped America. Cows enabled Europeans to successfully occupy the Continent. Cows, and the food grown to feed them, radically remodeled the nations landscape. Cows are partly responsible for Americans increasingly rotund bodies and poor health. Cows have exerted a remarkable degree of influence over our economic system, our politics, and our culture. Although cows themselves are now mostly hidden out of sight, cow molecules abound in every room of our houses. If gathered up and put on one side of a giant balancing scale, with humans on the other side, the cows living in the United States would weigh two and a half times as much as the human population.

Cows matter.

Our focus on cows began as a lark some years ago when we drove through Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and England. Leaving Edinburgh, we were immediately struck by the many small herds we saw. In the United States, even in farm country, we seldom see cows these daysthey have been moved off pastures and into confined feeding lots or giant dairy barns far from thoroughfares. Furthermore, the cows we saw in the British Isles appeared to come in more varieties. To add spice to the trip, we began competing to spot, and snap photos of, unusual cows.

Near the end of our trip, we had reservations at a thatched-roofed B&B deep in the verdant countryside of Devon, England. The tangle of one-lane country roads and the paucity of road signs prevented us from meeting our hostess till dusk. But there was still time for a short walk before dinner. Gailwho reliably gravitates toward any warm-blooded animalhad noticed a small herd of Holsteins grazing in a nearby pasture. White hides sporting Rorschach-like inkblots gave the cows a festive air.

We strolled down the hill toward them, picking our way around stones, bushes, and cow pies. Fifty feet from the cows, we paused, a flimsy hedge separating us from them.

The nearest cow was snacking on a tree. A tongue rolled out of its mouth like a muscular tsunami, wrapped itself around a small branch, and reeled the branch in. We edged closer. When we were about thirty feet away, the cow stopped eating and stared at us, leaves sticking out of both sides of its mouth. This cow was huge, easily five times as large as both of us combined. As city dwellers, we tend to forget just how large cows are. Relatively few Americans ever have a face-to-face encounter with the source of their milk and hamburgers. A trivial fraction of 1 percent of Americans has had the experience of milking a cow; an even smaller fraction has killed a cow to eat its flesh. We are more isolated from the source of our food than any previous generation.

The Holsteins tail switched back and forth. It wasnt a friendly sort of puppy-tail wagging or a lazy shoofly motion. The half-dozen other cows also stopped snacking and all of them stared at us. Not knowing any better, we stared back. In the air between us hung a bubble of mutual awareness.

Unlike horses, cows dont raise their heads high. The lowered heads, combined with unblinking stares, seemed menacing. Cows in those parts had no reason to trust or love humans. Over four million of them had recently been slaughtered and burned to prevent the spread of mad cow disease.

We knew that Holsteins were well regarded as milk cows, each cow now producing twice as much milk as a cow did in the 1960s, when we were in college. Our decision to stroll into the pasture had been prompted, in part, by our idle curiosity about these prodigious modern milk machines. The nearest cow pawed the ground. Gail nudged Denis and whispered, No udders. They must be bulls. Unlike the hornless Holsteins pictured on milk cartons, these animals had sturdy, sharp-tipped horns.

Denis squinted at the herd. Nope. Theyre steers. Still, a steer is no pushover.

From where we stood we couldnt tell if there was a fence buried in the hedgerow between us and the steers, or whether the barrier consisted only of delicate twigs and leaves. The lit windows of the B&B high behind us seemed far away in the gathering darkness. We backed off and returned to our lodgings.

Gails interest in cows outlasted the trip. Back home in Seattle, she began reading up on cows. Her conversation became peppered with cow facts. Did Denis know, for example, that cows sweat through their noses? That they have a magnetic sense and tend to align themselves in a north/south direction when grazing? On drives, John Pukites A Field Guide to Cows in hand, she started watching and identifying breeds of cows the way some people watch birds.

It was hard to find many cows to watch, however. Were the hidden-away cows being treated well? Books and articles made it clear that many factory-farmed cows were abused. She wondered whether it was possible, in the States, to catch a brain-eating disease from eating a well-cooked hamburger. What she learned was not reassuring.

Denis, with his broad interest in matters environmental and a penchant for hiking around obscure corners of the world, had always been more interested in endangered wild animals than in domesticated creatures. Eventually, though, he came to share Gails conviction that cows deserve more attention. Once he focused on cows, he found their heavy hoofprints on almost every major environmental problem. Compared to other meat sources (like pork and poultry), conventional grain-finished feedlot beef produces five times more global warming per calorie, requires eleven times more water, and uses twenty-eight times as much land. Eating a pound of beef has a greater climatic impact than burning a gallon of gasoline. And as he looked more carefully at feedlots and conventional dairy practices, Denis, too, became ashamed of how Americans treated cows.

From a tourists perspective, there appears to be a greater variety of cows in Britain than one sees from roads in the United States. Highland cow, Scotland. Photo: Lyda Boyer.

We both sensed that if we could just connect the dots, an important story might be revealed about the impact of Americas ninety-three million cowsroughly one hundred and twenty billion pounds of cowon our lives. We began to spend evenings reading about the curiously entangled lives of cows and Americans and discovered that cows cast considerable light on who we are as a people.

Next page