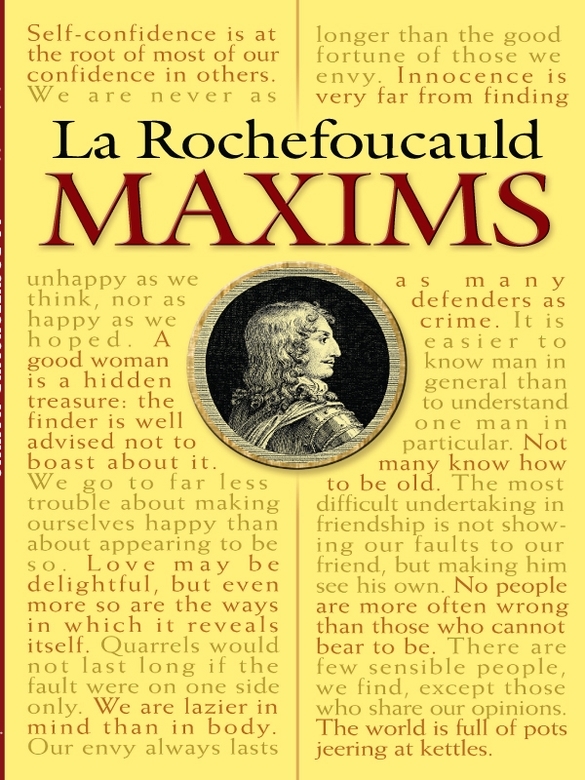

MAXIMS

V IRTUES, as we call them, are often a series of acts and interests which chance, or our own diligence, has arranged. Men are not always brave because courageous, nor women chaste because virtuous.

Vanity out-flatters the subtlest flatterer.

Explore as we may within the boundaries of our self-esteem, there remain undiscovered regions.

Conceit is more subtle than the most finished courtier.

We are no more masters of the duration of our passions than of the length of our days.

Passion often makes idiots of the wisest men, and clever men of fools.

Historians would have us believe that the most dazzling deeds are the results of deep-laid plans; more often they are the results of mens moods and passions. Thus, the war that Augustus waged against Antony, caused, we are told, by their ambition to be masters of the world, was, perchance, but the outcome of jealousy.

Enthusiasm is the only convincing orator; it is like the infallible rule of some function of Nature. An enthusiastic simpleton is more persuasive than a silver-tongued orator.

Our passions are so governed by injustice and self-interest that they are dangerous guides; suspect them most when they appear most logical.

In the human heart one generation of passions follows another; from the ashes of one springs the spark of the next.

One passion is often the parent of its antithesis; avarice gives birth to prodigality; prodigality to avarice; we are often firm because weak, or bold because timid.

However artfully we cloak our passions with piety and honor, the veil is yet transparent.

Egotism tolerates less kindly the censure of our tastes than that of our judgment.

Men not only forget benefits and injuries; they hate those toward whom they are under an obligation and cringe to those who have insulted them. Gratitude and revenge, as duties, are yokes that gall.

The magnanimity of princes is often but a policy to gain the love of their people.

Clemency, usually counted a virtue, is occasionally the outcome of vanity, sometimes of laziness, often of fear, and usually of all three.

Prosperity accounts for the content of the fortunate.

Self-control is a dread of that scorn and envy which people, overcome by their own happiness, deserve. It is a vain display of our moral strength. Self-control, in a word, is the desire of most successful men to appear greater than their achievements.

We all have strength to bear our neighbors burden.

The quiescence of the sage is but the art of masking his emotions.

A man condemned to die often affects a firmness and a scorn of death which, at bottom, are but his fear of facing it. And this stoicism is to his mind what the bandage is to his eyes.

Philosophy easily masters past and future ills, but the sorrow of the moment is the master of philosophy.

Few men have an intimate knowledge of death. We die not because of resignation, but from stupidity and custom, and most of us die because we cannot help it.

Great men who succumb to misfortunes make it evident that they have borne their past troubles from ambition, not from courage. Except for their great vanity heroes are but ordinary men.

It takes a better man to bear good luck than bad.

Death and the sun! Who can outstare them?

Often we boast of our most criminal passions, but envy is so mean and so sordid that we never admit it.

Jealousy is in a measure justifiable; it is a defense of our own property, or of what we think is ours; whereas envy cannot tolerate anothers wealth.

Our good qualities draw harsher criticism than our bad.

Our strength exceeds our will-power; hence we often excuse our failures by pleading the impossibility of success.

Had we no faults, we should not take such pleasure in discovering them in others.

Jealousy thrives on doubt; certainty goads it to fury, or ends it.

Pride is self-sufficient, and is unaffected though deprived of vanity.

It is our own pride that blames our neighbors pride.

The measure of pride is equal in all men; the difference lies in its manifestations.

It seems that Nature, which has so wisely constructed our bodies for our welfare, gave us pride to spare us the painful knowledge of our short-comings.

Pride plays a greater part than kindness in our censure of a neighbors faults. We criticise faults less to correct them, than to prove that we do not possess them.

Promises are measured by hope; performances by fear.

Egotism plays many parts, even that of altruism.

Interest blinds some men, but lights the path of others.

Undue attention to details tends to unfit us for greater enterprises.

We are too weak to follow our best judgment.

Man thinks he leads when he is being led; when his mind seeks one goal, his heart imperceptibly draws him towards another.

Strength or weakness of mind are but other names for our good or bad physical condition.

The vagaries of our moods are more capricious than those of Fortune.

The Philosophers love or scorn of life was a matter of personal taste, no more open to discussion than is our taste in food, or our choice of colors.

Our moods appraise each turn of fortune.

Content depends not on things themselves, but on their desirability; true happiness lies in the possession of that which pleases, not others, but ourselves.

We are never as happy or as unhappy as we think.

Self-satisfied men pride themselves on their misfortunes to persuade themselves, and others, that they are worthy to be the butts of fate.

Nothing so blights our self-esteem as to disapprove of what we once approved.

However great the discrepancies between mens lots, there is always a certain balance of joy and sorrow which equalizes all.

Great as are the advantages which Nature bestows, heroes are the children partly of genius, partly of chance.

The Philosophers scorn of wealth was but their secret ambition to exalt their merit above fortune by derising those blessings which Fate denied them. It was a ruse to shield them from the sordidness of poverty, and a subterfuge to attain that distinction which they could not achieve by wealth.

Our hatred of favorites is but a love of favor, and our scorn of those who enjoy it is only a balm to our vexation at being deprived thereof. We refuse a favorite our homage since we cannot deny him that which brings him the homage of others.

To gain a position in the world we go to any lengths to lead people to believe that we have one.

However much credit men may take for their achievements, chance is more often responsible than sagacity.

It seems that beneficent or malignant stars govern our deeds, and that to them we owe what praise or blame we receive.

A clever man reaps some benefit from the worst catastrophe, and a fool can turn even good luck to his disadvantage.

Fortune smiles most kindly upon her favorites.

Good or bad fortune depends no less on our moods than on chance.

Sincerity is open-heartedness. Few people have it; in most cases it is a delicate dissimulation practised to gain the confidence of others.

Our hatred of untruth is often an unconscious desire to add weight to our statements, and to sanctify our word.

Truth works less good in the world than its counterfeits work harm.

We cannot sufficiently praise prudence; yet the greatest prudence cannot with certainty predict the least event, since it acts on man... that most uncertain of all things mortal.

A wise man co-ordinates his interests, and develops them according to their merits. Cupidity defeats its own ends by following so many at once that in our greed for trifles we lose sight of important matters.