All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without prior written permission of the publisher.

232 Third St. #A111

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Cover design by Zoe Guttenplan. Interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

This book was made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

Archipelago Books also gratefully acknowledges the generous support from Lannan Foundation, the Carl Lesnor Family Foundation, the Nimick Forbesway Foundation, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

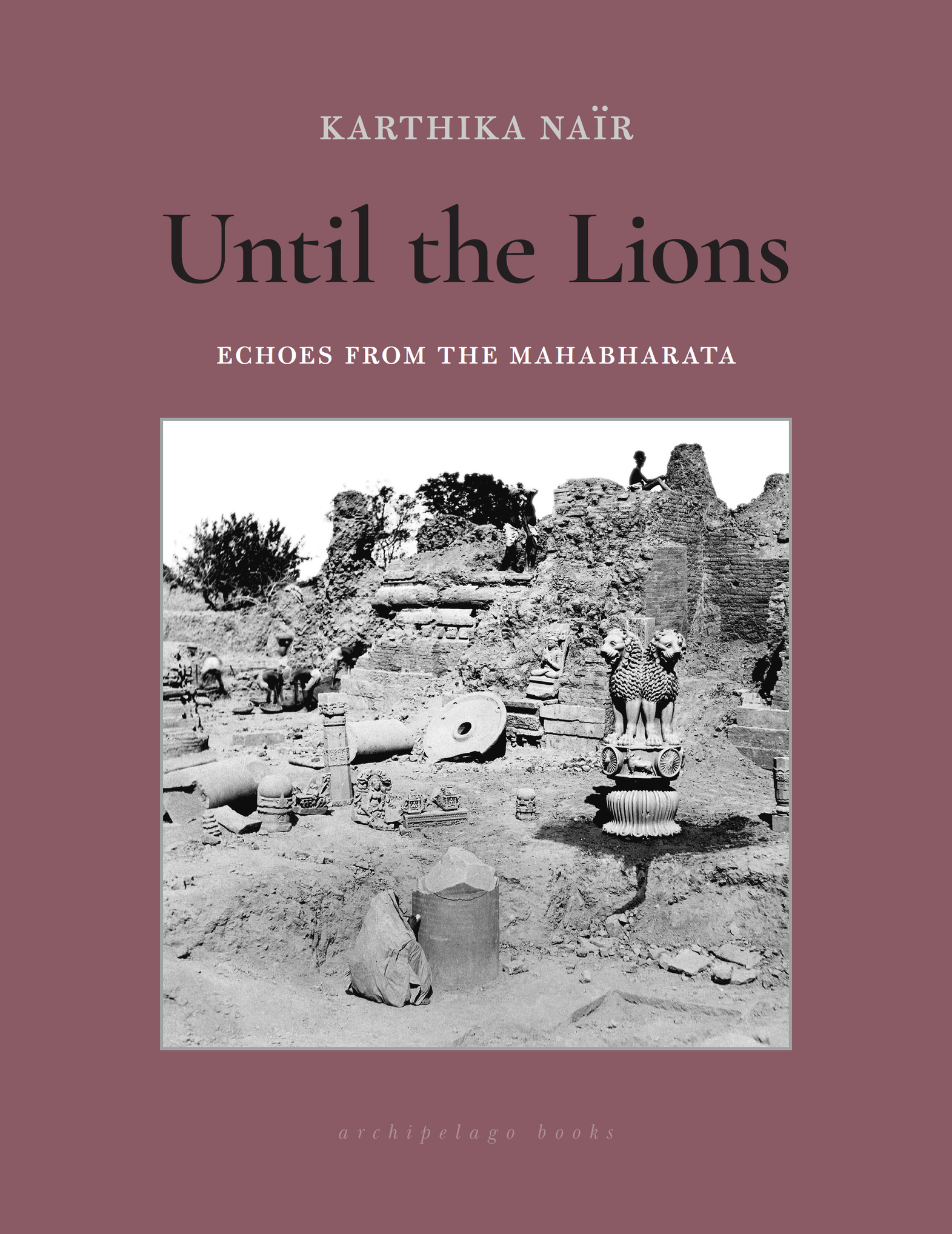

UNTIL THE LIONS: OF MYTHS AND MEN

When I was nine, my father overheard me bragging to friends, children of his colleagues in the army. Though he had not been injured in battle, he had fought in all three wars India had waged in the 1960s and 70s, and been recognised for his work feats I had been flaunting to secure my glazed brick on our particular social pyramid. Our lot had rather grim measures of hierarchy: so, the classmate whose parent had lost a limb in a bomb blast easily held the capstone; the rest of us were scrabbling below.

After he walked into our vicarious contest, my father didnt say much. That night, though, he quietly shared a few thoughts, memories, with me. First, that there were no altruistic battles, that countries engaged in warfare out of self-interest. There was nothing celebratory about military combat, he said: it was at best a necessary evil, all too often initiated in a show of political or national pride; once in a while, to defend land and freedom. Whatever the reason, it was undertaken at almost immeasurable cost.

There were, he said, few noble victors in war, seldom real saviour armies. Victory could stoke horrible reactions in human beings: it encouraged pillage and abuse even in ordinarily principled people. When men became conquerors, he said, they often paid for it by losing part of their humanity, only they didnt know it immediately. He didnt ever want to hear me boasting about his war record, because he had done what was necessary at that point, what many thousands of people had to. But it was not something one should want to relive, nor brandish as an achievement.

Most of what he explained did not make sense immediately; in fact, what I had felt then was a bewildered indignation that he would not let me crow about such exciting deeds. Yet, the words stayed close, sounding louder and clearer over time, as events around the world in Ireland, Iraq, Bosnia, Rwanda, Sri Lanka, Kashmir, Manipur, closer and closer home served to provide a brutal, ever-growing illustration.

By the time I began to write Until the Lions, those words had become an ostinato inside my head, with fragments echoing in various keys. Those words were ones I heard no more outside memory, as my father (like much of the world around him) gradually shifted to hawkish convictions about national identity and army impunity, and a growing distrust in the need for dissent.

Each of the characters in the book views one or more of the triggers and upshots of war through separate vantage points, whose existence I learnt from my fathers earlier, farsighted self. Each brings a reminder of the moral and physical price exacted on and outside the battlefield in victory and defeat by the unnamed wellspring of warfare: militant patriarchy. A patriarchy which demands ownership, appropriation: of land, of wealth, of qualities like heroism and honour, and, inevitably, of bodies, especially those considered an inferior other. Indigenous communities, lower castes, women.

Women. As another soldier remarked, throughout history women are among the first casualties of war and conflict. Their bodies become territories: possessed, ravaged, ploughed as though for produce, discarded, carelessly destroyed. But, unlike with land, the stigma of conquest is attached to their person; they become repositories of lost honour, individual and collective.

Salman Rushdie wrote most memorably on this in Shame, on the strange and expedient transfer of subjugation and dishonour from the men whove experienced defeat to the women who will suffer the consequences of that defeat and bear its scars on their bodies. Narratives across time echo this enduring practice of violence and violation inflicted on women, whether through Briseis and Cassandra in Homers Iliad, Sita and Shoorpanaka in Valmikis Ramayana, or the daughters of El Cid in El Poema de mio Cid.

But why the Mahabharata: that is a question asked frequently. After all, this age scarcely has a shortage of accounts of large-scale conflicts and their aftermath. Why not write a brand-new story, anchored by the present, set in an identifiable place?

Perhaps because foundational epics remain instantly identifiable. They contain the essence of the human experience, whichever the era or continent they are (re)discovered in, and however different the civilisation. They reflect the richness and complexity of humankind, its capacity for betrayal, cruelty, enduring hate, and also for breath-taking generosity and love. They know the cadences of the human heart and can deliver them through universally recognisable, even familiar, chords. Ambition, greed, arrogance, envy. Tenderness, desire, loyalty, sacrifice. Foundational epics highlight them all, their conflicting presence, within the same characters sometimes within the same chapter.

And the Mahabharata, specifically? Like many Asians, I would be hard-pressed to say just when this epic first flew across my consciousness, how it found a permanent perch there. Was it during intricate all-night kathakali performances where gods, heroes and villains resplendent in ornate costumes and fiery masks descended on stage to effortlessly own attention and memory? Through thunderous fantasy films? Nightly sessions in preschool years with a raconteur great-aunt? Was it a recital of Ved Vyaasas text, deemed the original, or a regional variation, Tamil, Bhil, Javanese? Or Amar Chitra Katha comics those early conduits to myth, legend and history for generations of Indians (region, religion, language no bar)?