Untimely Meditations

1.The Agony of Eros

Byung-Chul Han

2.On Hitlers Mein Kampf: The Poetics of National Socialism

Albrecht Koschorke

3.In the Swarm: Digital Prospects

Byung-Chul Han

4.The Terror of Evidence

Marcus Steinweg

5.All and Nothing: A Digital Apocalypse

Martin Burckhardt and Dirk Hfer

6.Positive Nihilism: My Confrontation with Heidegger

Hartmut Lange

7.Inconsistencies

Marcus Steinweg

8.Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese

Byung-Chul Han

9.Topology of Violence

Byung-Chul Han

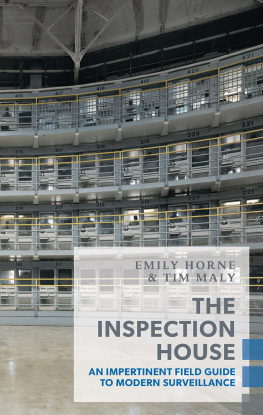

10.The Radical Fool of Capitalism: On Jeremy Bentham, the Panopticon, and the Auto-Icon

Christian Welzbacher

The Radical Fool of Capitalism

On Jeremy Bentham, the Panopticon, and the Auto-Icon

Christian Welzbacher

translated by Elisabeth Lauffer

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Originally published as Der radikale Narr des Kapitals: Jeremy Bentham, das Panoptikum und die Auto-Ikone by Matthes & Seitz Berlin: Matthes & Seitz Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Berlin 2011.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in PF DinText Pro by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Welzbacher, Christian, author.

Title: The radical fool of capitalism : on Jeremy Bentham, the Panopticon, and the Auto-icon / Christian Welzbacher ; translated by Elisabeth Lauffer.

Other titles: Radikale Narr des Kapitals. English

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, 2018. | Series: Untimely meditations ; 10 | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017047695 | ISBN 9780262535496 (pbk. : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262347129

Subjects: LCSH: Bentham, Jeremy, 17481832. | Bentham, Jeremy, 17481832. Panopticon. | Bentham, Jeremy, 17481832. Auto-icon.

Classification: LCC B1574.B34 W4513 2018 | DDC 192dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017047695

ePub Version 1.0

For Vera, Kadidja

and for Elmar

I was, however, a great reformist; but never suspected that the people in power were against reform. I supposed they only wanted to know what was good in order to embrace it.

Jeremy Bentham, conversation with John Bowring, London, February 2, 1827

I must praise my friend Bentham, that radical fool; hes aging well, and that despite being several weeks my senior.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, conversation with Johann Peter Eckermann, Weimar, March 17, 1830

The Theory behind the Practice

Jeremy Benthams Auto-Icon, produced 18321833. Today on display at University College London.

Jeremy Bentham (17481832)born within a few weeks of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the firstborn son of an influential London barrister, a trained jurist, a leading political and moral philosopher of the Enlightenment, and the founder of utilitarianismwas a theorist of action. With regard to the fulfillment of Being in happiness, he considered his deliberations not only useful but practical. He personally endorsed the applicability of his ideas, even beyond the end of his life. His final manuscript, entitled Auto-Icon, discusses possible uses of the dead to benefit later generations. Bentham died before finishing the text, but the theories it contained were effectively sealed by means of his decision to have his body preserved and put on display. Hes aging well: to this day, Bentham sits in a cabinet constructed specifically for this purpose at University College London, armed with his cane and dressed in a frock coat and disproportionately large hat. As an Auto-Icon, he observes the goings-on and regularly receives students, disciples, and even critics.

An audience with Bentham immediately invokes a host of topics that defined his second seminal work of applied philosophy, the considerably more famous Panopticon, or The Inspection-House, published in 1791. First, what was the practical value of philosophical ideas? This question dogged Bentham all his life; it drew him out of the splendid isolation of the intellectuals existence and continually pushed him into conflict with the crown and Parliament. Second, and connected to the first, is the question regarding the line between solemnity and jest. Bentham plumbed its depths with radical folly, driving the question to conceptual and tangible extremes and into the realm of the absurd. Third is the question of the line between truth and illusion. In the Panopticon, this manifests in the impenetrable gaze of the warden, who monitors the cells with a sweeping view from a chamber at the center of the structure while remaining hidden from view, or seeing without being seen. As for the Auto-Icon, this question resides within the character of the effigyrepresentative images of rulers that circulated widely in eighteenth-century England and France, which were honored in place of the person and could even exercise jurisdiction in the Middle Ages. Fourth, and also connected, is the question of symbolic representationwhether of the body or architecture.

The questions Bentham poses feel familiar and current. Poised historically on the brink of the Enlightenment, American independence, and the French Revolution, the philosopher clearly knew to invoke topoi that would come to define the modern era and that reverberate to this day. In the Panopticon, Bentham saw a pedagogical instrument incorporating the tenets of reason, as it were. Construction and function, plan and influence, architecture and politics are brought into alignment. Bentham extoled the discovery in words that could easily be ascribed to Le Corbusier, Bruno Taut, or any other representative of classic modernism. What is architecture? Walter Gropius asked in April 1919, answering, The crystalline expression of mans noblest thoughts, his ardour, his humanity, his faith, his religion! In the Panopticon, Bentham writes:

Morals reformedhealth preservedindustry invigoratedinstruction diffusedpublic burthens lightenedEconomy seated, as it were, upon a rockthe Gordian knot of the Poor-Laws are not cut, but untiedall by a simple idea in Architecture!

Architecture (or the art of construction) as an agent of edification, orin more general termsculture as an agent of moral legitimation: this idea reflects a basic theme of sociopolitical change after 1750, which is closely tied to the emergence of the middle class as the dominating social stratum. This bourgeois element, which pervades the antimonarchic Benthams works in various forms, cemented his reputation at the time as a reformer and radical. Benthamwho assumed that human happiness was not only quantifiable but tied directly to the pursuit of money and good(s)was the philosopher of the bourgeois elite, the merchant class, and of capital itself. In a world after Adam Smith, he championed the view that economics essentially self-regulating nature would recast society as a functioning whole, based on logic and a rational foundation evidenced in Creation itself. In response to this reasoningand its resonanceKarl Marx unreservedly eviscerated Bentham.

In the 1960s, when the rediscovery of the