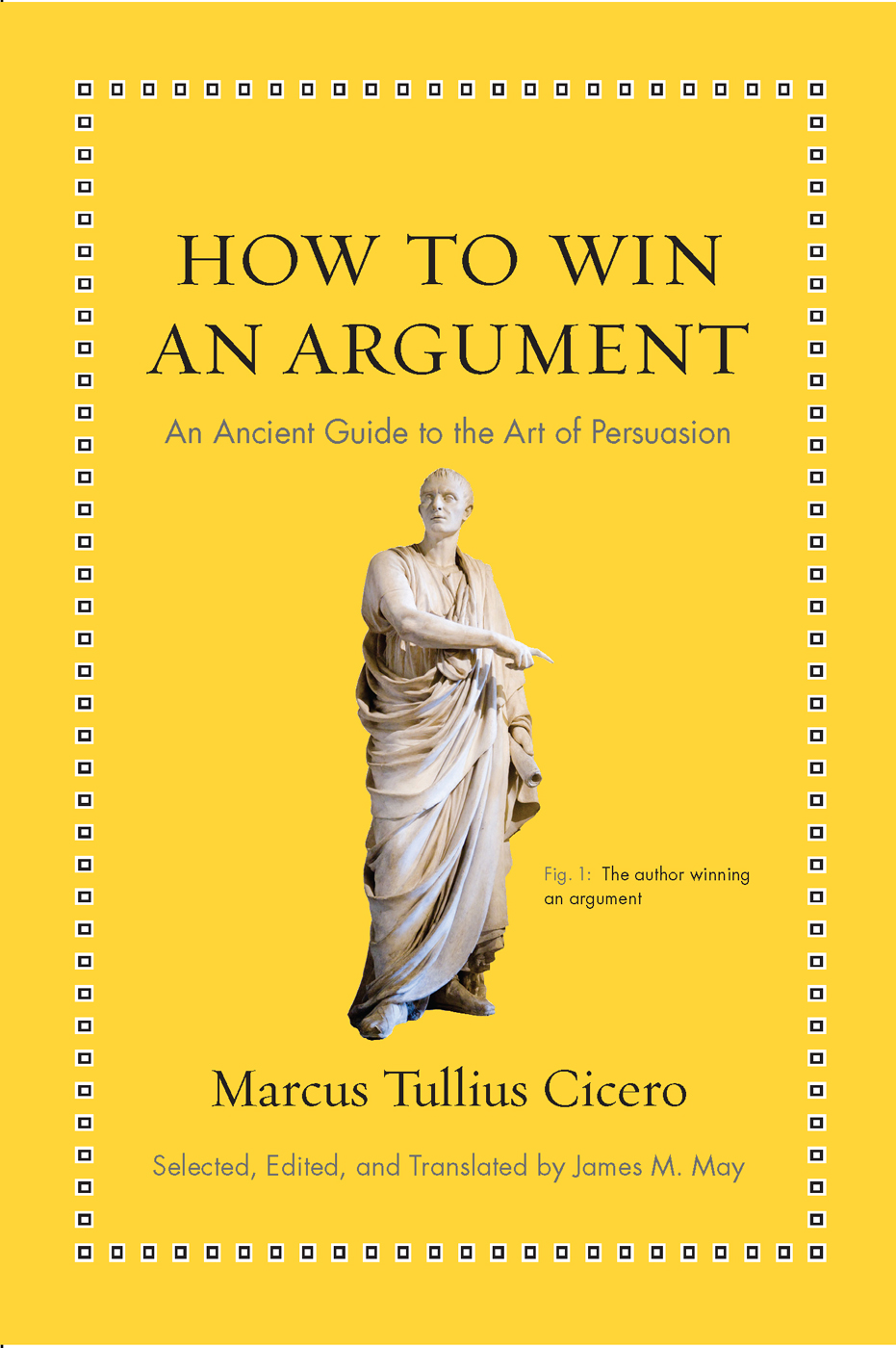

HOW TO WIN AN ARGUMENT

HOW TO WIN AN ARGUMENT

An Ancient Guide to the Art of Persuasion

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Selected, Edited, and Translated

by James M. May

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2016 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Ancient marble portrait bust.

Courtesy of Shutterstock Gilmanshin.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cicero, Marcus Tullius, author. | May, James M., editor, translator.

Title: How to win an argument : an ancient guide to the art of persuasion / Marcus Tullius Cicero ; selected, edited, and translated by James M. May.

Description: Princeton ; Oxford : Princeton University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016012361 | ISBN 9780691164335 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Rhetoric, Ancient. | Persuasion (Rhetoric) | Cicero, Marcus Tullius.

Classification: LCC PA6307.A2 M39 2016 | DDC 808dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016012361

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Stemple Garamond and Futura

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

PREFACE

For as long as human beings have had the ability to communicate, we have endeavored to persuade one another. Whether it be for the purposes of mere survival, or to control the circumstances of our lives, or to bring someone around to our way of thinking, or merely to win an argument, we have relied on some form of persuasioneither physical force or, what we would consider more civilized means, speaking and writingto accomplish our goals and purposes. The art of verbal persuasion, in a word rhetoric, was discovered in the West in the democracies of Syracuse and Athens during the fifth century BC. Citizens in democratic societies were expected to express themselves in assembly, represent themselves in courts of law, and participate in other civic functions. As a result, in order to enable people to operate successfully in society, attempts were made to describe effective means of verbal persuasion, and a theoretical system evolved that enabled citizens to plan and execute a successful speech in publicin other words, to win an argument.

Several centuries later, Romes greatest orator and one of the greatest speakers of all time, Marcus Tullius Cicero, secured Romes highest political office, the consulship, having relied heavily on this art of verbal persuasion to make a name for himself in Roman society. Trained from boyhood in the technicalities of rhetoric, Cicero excelled not only as an effective public speaker, who won the vast majority of arguments in which he was involved, but also as a theorist in the art of verbal persuasion, having written during his lifetime several treatises that have rhetoric as their subject. And although he is highly critical of the typical rhetorical handbooks of the day, he was, nonetheless, steeped in their doctrine and reliant upon their methods. In fact, this rhetorical education for civic duty, handed down by the Greeks and adopted by the Romans, remained a primary element in the training of all educated people throughout the Middle Ages, into the Renaissance, and even down into modern times.

Given the centrality of rhetoric, that is, the art of verbal persuasion, in our Western tradition, I present here a short anthology of passages from Ciceros writings, primarily his rhetorical treatises, that capture the essence of this ancient rhetorical system of persuasion, a system that helped to make Cicero and countless other orators effective speakers, able to convince people and win arguments. Readers will, I hope, find these selections interesting in their own right, as well as useful when thinking about their own efforts to persuade. Indeed, whether arguing with a friend over a trivial issue or presenting a brief before the Supreme Court, the goal of a speaker is still to persuade, and knowing the most effective means of persuasion in any given circumstance will lead to the successful realization of that goal. A peculiar paradox of contemporary American society is that, at a time when we find many schools, colleges, and universities talking seriously about fostering oral competency and good communication skills in their students, we actually see very few effective public speakers in action, in the courts, in our communities, or in the public arena of political life. While this book is certainly not intended to remedy that situation, my hope is that those who think about speaking in public and want to win arguments will find it appealing, and will delight in the realization that the techniques for effective oral persuasion discovered and enunciated millennia ago still make sense and have great relevance for those who would speak convincingly today.

In order to simplify matters and allow for smoother reading, I have avoided appending footnotes to names and terms that might present challenges to readers who are unfamiliar with the historical period or the technical subject matter. In lieu of such notes, a glossary of names and terms has been included near the end of the volume to which the reader can refer when seeking more detailed information or clarification. In addition, a list of suggestions for further reading on the subject has also been appended, consisting of both primary works by Cicero in English translation as well as secondary works that elucidate and comment upon ancient rhetoric and oratory, Cicero, and his works. All translations, except those from De oratore, are my own. De oratore passages were previously translated jointly by my colleague, Jakob Wisse, and me, and appeared originally in our complete translation of the treatise, published by Oxford University Press in 2001, Cicero: On the Ideal Orator. Occasionally, I have altered a word or two of that original translation in the passages that appear here.

I would like to thank Mr. Robert Tempio, executive editor and Humanities Group publisher for Princeton University Press, for suggesting this volume to me, and for his guidance and direction in seeing it through to publication; and Sara Lerner, senior production editor. I owe a debt of gratitude also to my copyeditor, Jennifer Harris, and to the anonymous referees of the Press, whose corrections, observations, and suggestions improved the manuscript greatly. I dedicate this little book to Augustus James May, in the hopes that, as he grows in age and wisdom, he will realize the ideal of the Elder Cato, becoming a vir bonus dicendi peritus (a good man, skilled in speaking).

James M. May

ST. OLAF COLLEGE

CICEROS LIFE: A BRIEF SKETCH

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born on 3 January, 106 BC, in Arpinum, a town approximately 70 miles southeast of Rome to a family that, though not members of the Roman nobility, was prominent in the local community and had important connections in the capital. While Marcus and his brother, Quintus, were still boys, the family moved to Rome, a move aimed at advancing the education and prospects of the brothers; there the boys were brought into contact with the two leading orators of the day, Lucius Licinius Crassus and Marcus Antonius, who were later to become the two chief speakers in Ciceros greatest rhetorical treatise, a dialogue on the ideal orator,

Next page