Contents

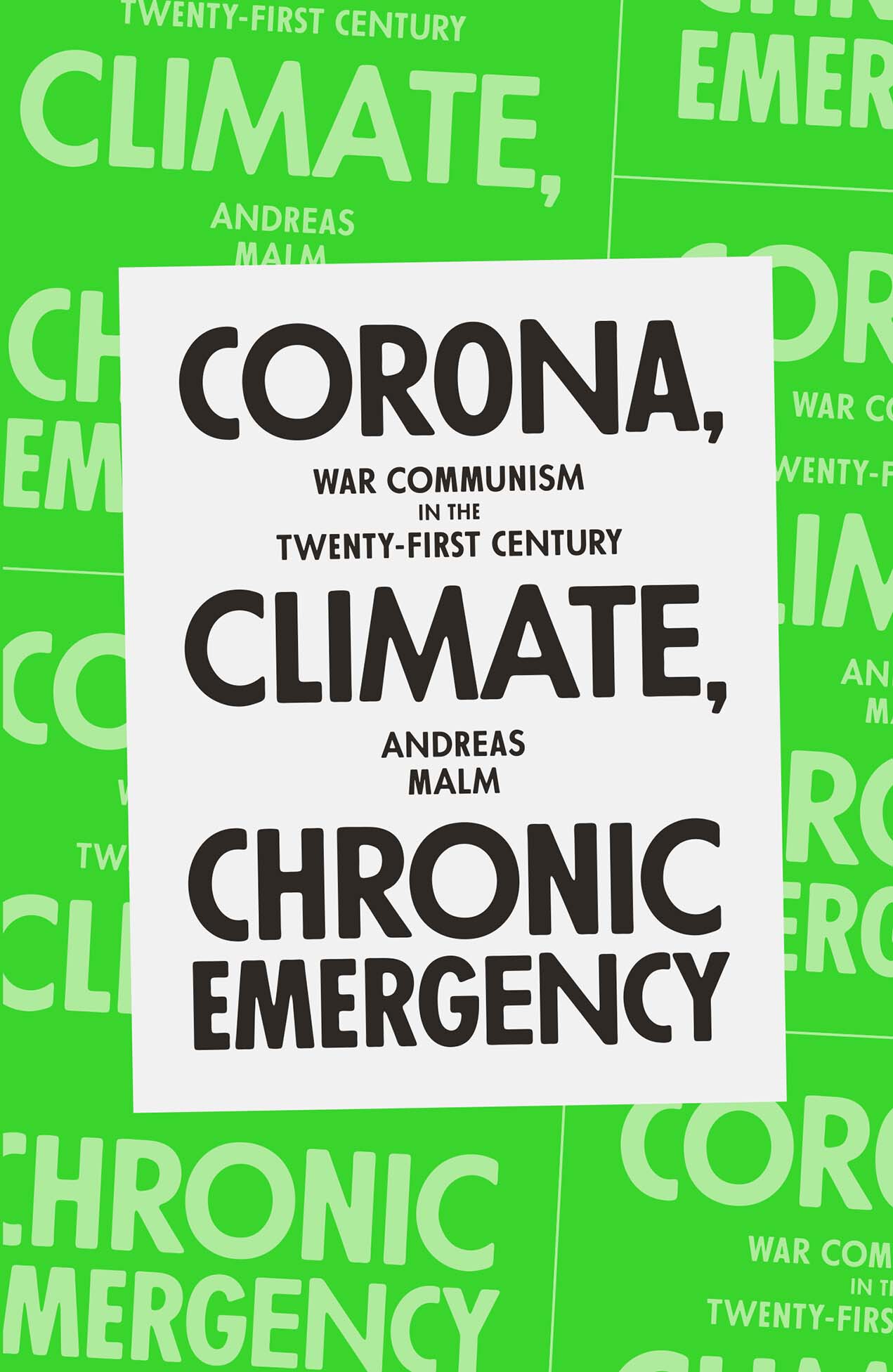

CORONA, CLIMATE, CHRONIC EMERGENCY

CORONA, CLIMATE,

CHRONIC EMERGENCY

War Communism in the Twenty-First Century

Andreas Malm

First published by Verso 2020

Andreas Malm 2020

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-215-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-217-8 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-216-1 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020941435

Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY.

Contents

The third decade of the millennium began with the signing of another historic stimulus package for the dystopian imagination. Bushfires still roared through Australia, incinerating an area larger than Austria and Hungary combined, shooting flames seventy metres into the sky, immolating thirty-four humans and more than one billion animals, sending smoke all the way across the Pacific Ocean to Argentina and colouring the snow over the New Zealand mountains brown, when a virus jumped out of a food market in Wuhan, China. The market offered animals caught in the wild. There were wolf pups on sale, as well as bamboo rats, golden cicadas, hedgehogs, squirrels, foxes, civets, turtles, salamanders, crocodiles and snakes. Early studies pointed, however, to bats as the source of the virus. From that natural host, the virus would have jumped to some other species pangolins were a prime suspect travelled into the Wuhan market and made the leap into some of the human bodies circulating through the stores. Patients began to stream to hospitals. One of the first, an otherwise healthy forty-one-year-old man who worked at the market, spent a week with fever, tight chest, dry cough and various pains during this week, coincidentally, temperatures in the afflicted Australian states sizzled above forty degrees before being rushed into an intensive care unit.

Then the virus propagated through the world like a pulse through a grid. At the start of February 2020, some fifty people died every day, mostly from acute respiratory distress and failure, or not being able to breathe; by the first days of March, the daily global casualty toll stood at seventy; by the first of April, at 5,000, the exponential growth curve now nearly vertical. With at least one case of infection reported in 182 out of 202 countries, the pulse of death had crossed every ocean and streamed through streets from Belgium to Ecuador. And while this was happening, swarms of locusts larger and denser than any in living memory swept through east Africa and west Asia, covering the land, eating plants and fruits and leaving little if anything green behind. Farmers made bootless attempts to swat them away from fields. The clouds of locusts darkened the skies and, when falling dead, piled up in masses thick enough to stop trains in their tracks. One single living swarm in Kenya embodied an area three times that of New York City; a more normal contingent would have been one twenty-fourth that size and still contained up to 8 billion individuals, with an ability to devour the equivalent of what 4 million people eat in a day. Under normal conditions, any such swarms would be few and far between. The locust would stick to its solitary lifestyle in the deserts. But in 2018 and 2019, those deserts were showered with abnormal cyclones and torrential downpours, depositing such an excess of moisture that the eggs of the locusts multiplied into congregations so voracious as to threaten the food supplies of tens of millions of people, just as the virus descended.

No horseman of the apocalypse rides alone; plagues do not appear in the singular. It looks like there will be boils and thunder and pestilence and stinking rivers and dead fish and frogs in the kneading bowls. When these words are written, in the first days of April 2020, the total number of registered cases in the coronavirus pandemic is about to breach the one million threshold and the number of dead to pass 50,000 and no one knows how this will end. To paraphrase Lenin, its as though decades have been crammed into weeks, the world spinning in a higher gear, leaving every forecast liable to embarrassment. But if we cash some of the cheques written to the imagination, we can envision a fevered planet inhabited by people with fevers: there will be global heating plus pandemics, slums sinking into the sea with people dying from pneumonia in, for example, Mumbai. The slum of Dharavi just reported its first case of the coronavirus. One million people live in close quarters in Dharavi, with minimal access to sanitary facilities, and every year storm surges invade the slum with higher waters. There will be refugee camps where pathogens eat their way through crowded bodies like a fuse through a wire. It will be too hot, and there will be too much contagion, to step outside. Fields will crack under the sun with no one to tend them but on the other hand, the corona crisis came from the start with the promise of a return to normality, and this promise was unusually loud and credible, because the malady seemed far more external to the system than, say, the crash of an investment bank. The virus was the epitome of an exogenous shock. It would fizzle out, one month or the next. There might be a second wave but still that would be it. A vaccine could choke off the pandemic. Every measure taken to contain it was advertised as temporary, like police tape marking off a street, and so we can just as easily envision a planet lifted back to the status quo ante. The streets will fill up again. Shoppers will throw away their face masks with relief and throng the malls. There will be a pent-up urge for everyone to pick up where they left off when the virus struck, and it will be released with gusto: airliners back in the sky, their canopy of white contrails budding as if after winter. Private consumption might be more alluring than ever. Who would want to stand on a packed bus or train after this? Unutilised capacity in car and steel and coal plants will burst forth and stockpiled inputs fall in line with the supply chains. Out of sight, the oil drills back in operation, hammering away.

But these two opposing scenarios of the future are, on closer inspection, exactly one and the same.

Can there also be a way out?

Where an emergency exists

To hinder or at least slow down the spread of the virus, states across the globe took extraordinary in every sense of the word measures to confine their citizens to their homes. Lockdowns were implemented with various degrees of policing, some draconian. European prohibitions covered activities ranging from mingling with more than one other individual (Germany) to leaving the house without a permit (France) to leaving the house without a parent if youre under eighteen (Poland) to crossing into another municipality (Italy) to picnicking in a park, popping into a pub, dining in a restaurant and receiving foreign visitors (most countries). By early April, the generality of the human species fell under some version of shutdown. Never before had the business-as-usual of late capitalism been so utterly suspended.