Managing the Wild

Managing

the Wild

Stories of People and Plants and Tropical Forests

Charles M. Peters

A co-publication of The New York Botanical Garden Press and Yale University Press.

Copyright 2018 by Charles M. Peters.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Roman type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017943418

ISBN: 978-0-300-22933-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In Memoriam

Charles Merideth Peters

19201974

Susan Daves Peters

19242010

Stories are one of the fundamental ways in which we understand the world. They are probably our best maps and models of the worldand we may yet come to learn that the reason for this is that stories are some of the basic constituents of the world.

ROBERT BRINGHURST, The Tree of Meaning: Language, Mind and Ecology, 2006

Contents

INTRODUCTION

The Challenge of Sustainable Forest Use

ONE

The Ramn Tree and the Maya

TWO

Mexican Bark Paper

Commercialization of a Pre-Hispanic Technology

THREE

Camu-camu

Fruits, Floods, and Vitamin C

FOUR

Fruits from the Amazon Floodplain

FIVE

Forest Fruits of Borneo

SIX

Homemade Dayak Forests

SEVEN

Sawmills and Sustainability in Papua New Guinea

EIGHT

Collaborative Conservation in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest Reserve

NINE

A Renewable Supply of Carving Wood

TEN

Caboclo Forestry in the Tapajs-Arapiuns Extractive Reserve

ELEVEN

Measuring Tree Growth with Maya Foresters

TWELVE

Managing Agave, Distilling Mescal

THIRTEEN

Landscape Dynamics in Southwestern China

FOURTEEN

The World of Rattan

FIFTEEN

Community Forestry in Myanmar

Preface

This is a book of stories about indigenous forest management written by a scientist who has spent thirty years working closely with rural communities in tropical forests. With few exceptions, the communities depend on a variety of forest plants for their livelihood. These may be timber trees, edible fruits, spiny vines, barks for paper, or even the leaf bases of certain agaves that can be fermented to produce an alcoholic beverage. The relationships developed between the people in the community and the plants in the forest are subtle, yet surprisingly complex, and in the narratives offered here I describe a dimension of tropical forest use that has rarely been presented. The conventional view in industrialized countries holds that native populations have been exploiting local forest resources with little regard for the future, cutting and burning large areas of tropical forest, and depleting innumerable tropical plant resources. But such actions represent only one aspect of the interaction of communities with local forests. In every tropical region of the world, communities also work to plant trees, select favorable genotypes, weed, thin, and manage forests, and do their best to control harvesting to conform to the rate at which a given resource is produced. These are the activities I focus on in this book.

As an ecologist and a forester, I have been most impressed during my fieldwork by how much villagers know about the properties and uses of local plants and the intricacies of what needs to be done to promote the regeneration and growth of a particular species in the forest. Their application of this knowledge, year after year for hundreds of years, has changed the structure and composition of tropical forests, but these interventions can be hard to discern. Because outsiders frequently do not recognize the imprint of local managementand because they are often unwilling to ask the people doing the managingthey might assume that nothing purposeful is being done to sustain local forests. I have had the good fortune to learn, and in some cases to be part of, the backstory of a number of positive interactions between a community and a tropical forest.

I have compiled these narratives here to offer a different perspective on what happens when human beings and tropical forest interact. Using examples from Central and South America, Southeast Asia, and Africa, I focus primarily on my collaborations with different communities to manage tropical forests sustainably, as well as my work documenting ways communities were already doing this. I conducted household surveys, ran inventory transects, counted and measured thousands of trees, quantified annual growth, and sampled an inestimable number of native fruits, but most of all I asked a lot of questionsand I listened. This is how I found most of my stories.

I wrote this book for people who would like to know more about how indigenous communities that have lived in a tropical forest for hundreds of years manage to do so without depleting their resource base; for those who are interested in what happens when colonists move into a new area of forest and wish to exploit it commercially; and for readers who are curious about the incredible variety of different fruits and fibers and timbers and oleo-resins and latexes and medicinal plants that are produced in tropical forests. I aim as well to show policy makers, resource managers, and conservation advocates the potential benefits of giving communities a more prominent role in the conservation of local tropical forests.

Forest dwellers have been exploiting plant resources in tropical forests at varying intensities for thousands of years; I have spent the past three decades looking into the nuances of this interaction. I have found that different communities do different things, that they do these things for their own reasons, and that some of their interactions with the forest are both skillful and sophisticatedbeneficial to the community with minimal long-term impact on the forest. The current understanding that many in the industrial West hold of tropical forests seems to be largely defined by the tension created between the concepts of wild and managed. There is a tendency to think, If its wild, we should probably keep everybody out, and to deny the management they cannot recognize. I hope here to help resolve, or at least explore, this tension, and add useful new details to the worlds understanding of forest use in the tropics.

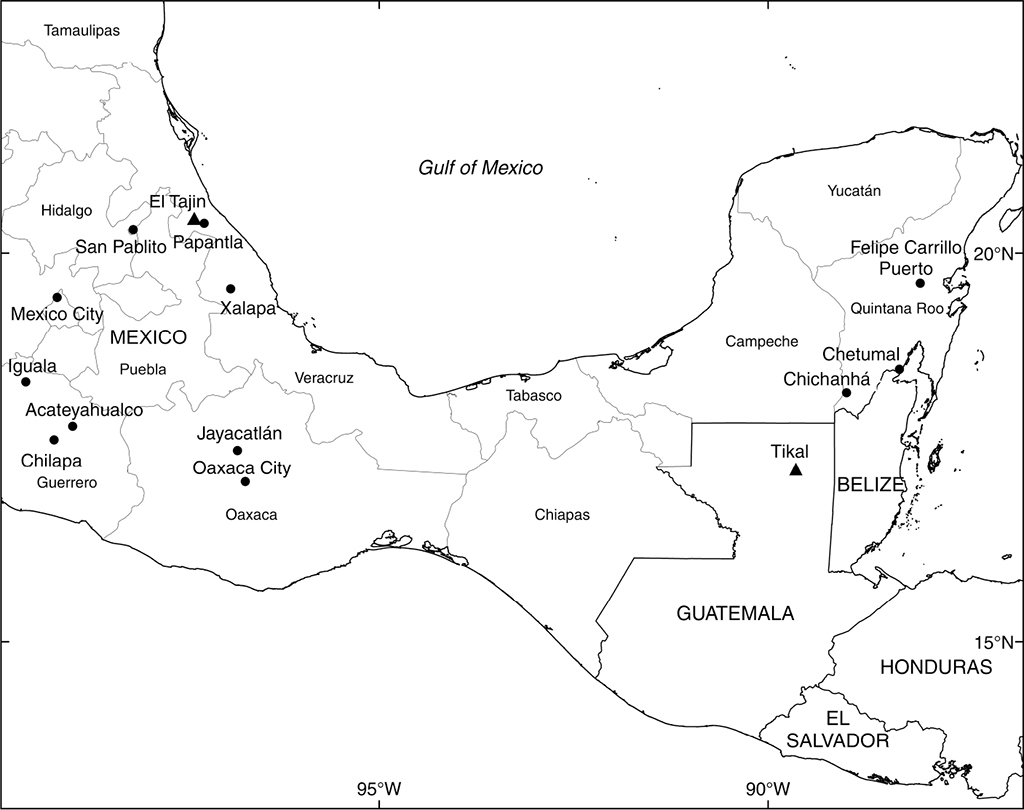

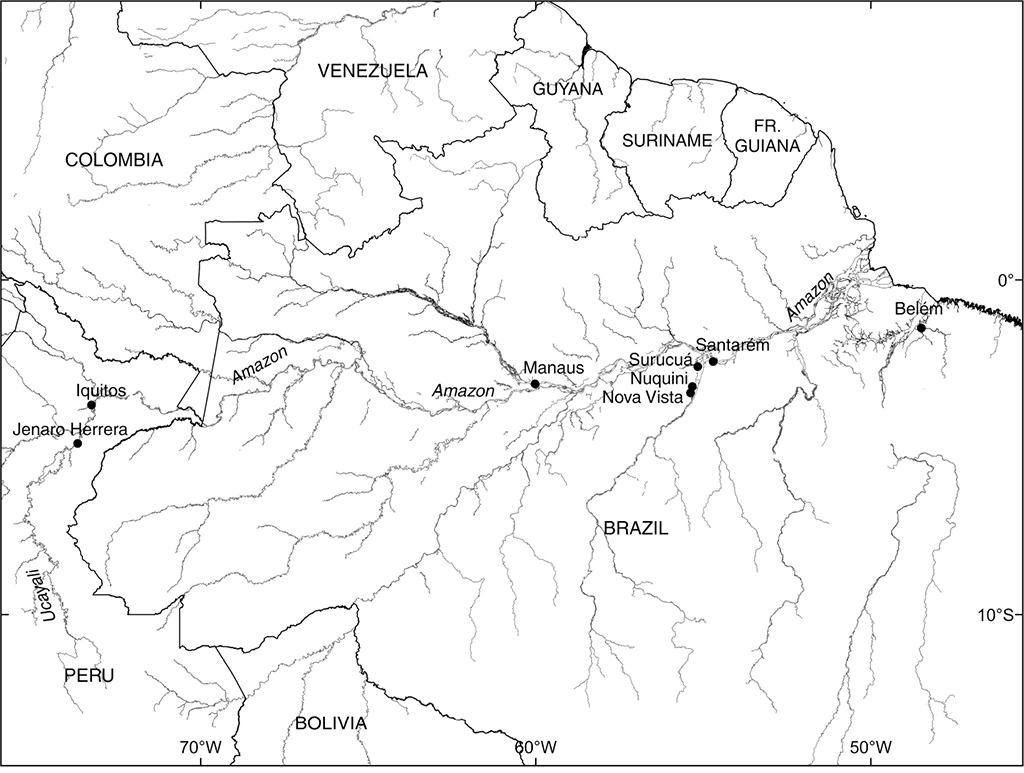

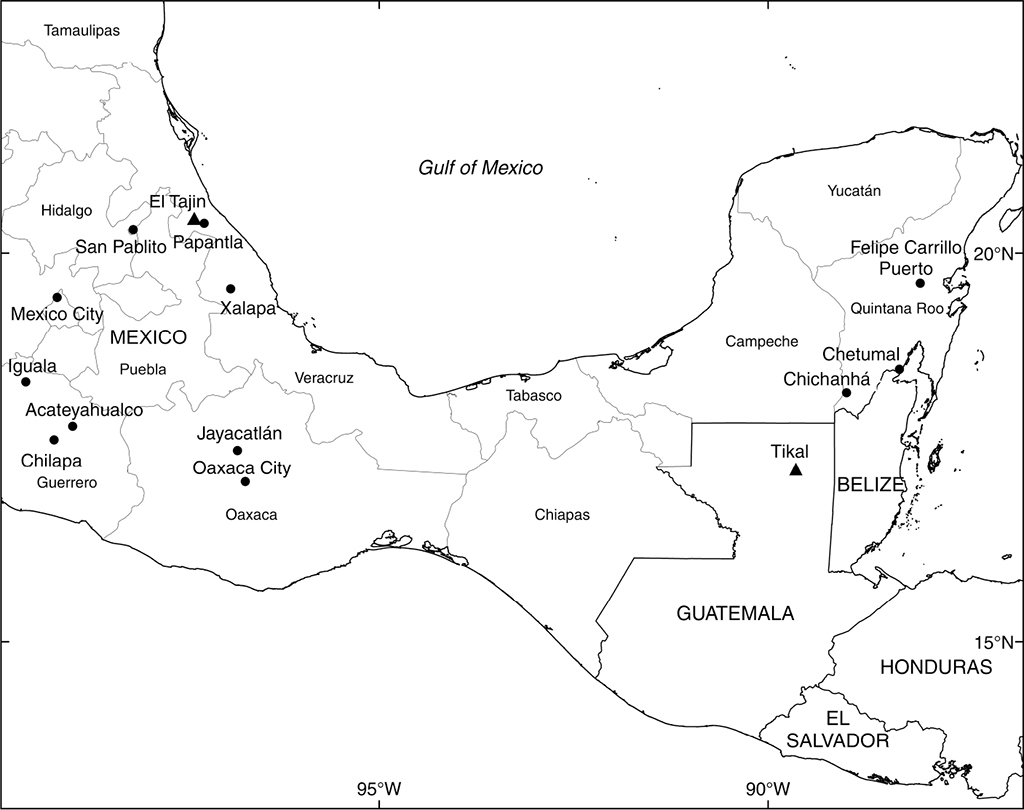

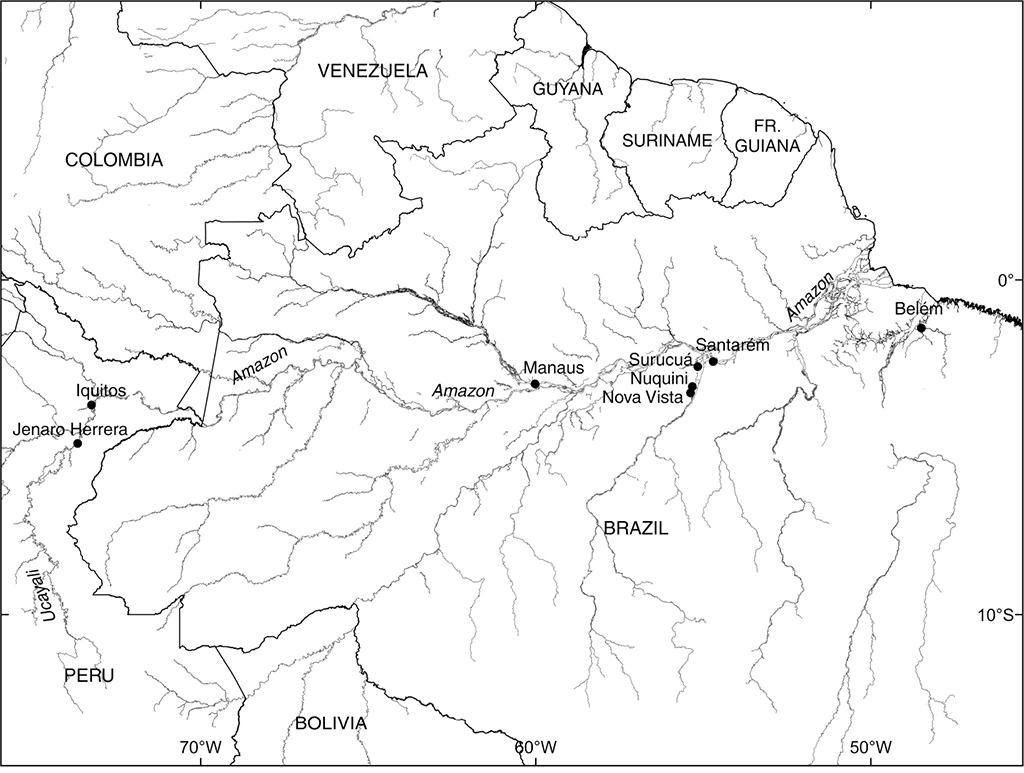

Maps

The maps that follow show the places where I conducted projects focused on the use and management of tropical forests by local communities. Each map is keyed to the chapter or chapters in which these projects are discussed.

Mexico (1, 2, 9, 11, 12)

Amazonia (3, 4, 10)

Next page