Beauty is worse than wine; it intoxicates both the holder and the beholder.

ALDOUS HUXLEY

Contents

Guide

The sight of something lovely doesnt just bring us pleasure, it physically motivates us. Writing in the New York Times, Lance Hosey points to brain scan studies that reveal that the sight of an attractive product can trigger the part of the motor cerebellum that governs hand movement. Instinctively, we reach out for attractive things; beauty literally moves us.

It is the desire for that beautynot cataclysms or migrations, wars or empires, kings or prophetsthat drives us and shapes us. What moves the world is the same thing that moves each of us.

The history of the world is the history of desire.

Theres no more basic statement than I want.

I, unfortunately, want almost everything. Its been a lifelong affliction...

Money may make the world go round, but only because money is a means to an end: that singular, almost lunatic, human desire to truly possess, and keep forever, a thing of beauty.

All of human history can be boiled down to these three verbs: want, take, and have. And what better illustration of this principle than the history of jewelry? After all, empires have been built on the economics of desire, and jewelry has traditionally been a major form of currency.

Ive always most especially loved jewelry. My mother didnt have a jewelry box. She had a jewelry closet. Some of the pieces were real, some of them were fake. It didnt really matterit all held me in equal thrall; it was all real treasure. When I was good, she would let me sit on her giant bed and sort it into sparkling piles, and rearrange all the drawers and boxes. That was somehow more satisfying even than trying it on. Touching every glittering piece, cataloging them in my mind: how many, what kind. I wanted them so badly for my own, that it was like an unrequited love, the kind that leaves an empty pit in your stomach.

Even as an adultone who, as a jewelry designer, has spent the last decade surrounded by jewelsmy moms jewelry has never quite lost that magic sparkle. I still want her jewelry. It doesnt matter that our taste couldnt be more disparate, nor that Ive amassed quite a jewel closet of my own. The moment she shows me a new and shiny thing shes acquired, Im right back on that giant bed, surrounded by her gaudy eighties cocktail jewelry, holding some glittery piece in my tiny hands as though it were the Holy Grail.

Why is that? Why do I need every trinket she buys? Why do I inflate the value of her possessions so absurdly?

Its because theyre not just objects. Not by a long shot. Jewelry is symbol and signifier, a tangible stand-in for intangible things. It can mean not just wealth and power but also safety and home. It can evoke glamour or success or just your moms bed.

The individual stories collected and retold here are stories about beautiful things and the men and women who desired them. They are stories of need and possession, longing and greed. But Stoned is more than a book about pretty things. Its an attempt to understand history through the lens of desire, and a look at the surprising consequences of the economics of scarcity and demand. Stoned is about the rippling effect that a rare and coveted piece of jewelry can have over the course of an individual lifetime and over the course of history. Pieces of jewelry have spawned cultural movements, launched political dynasties, and even started wars, or at least, been major contributing causes of political and military conflict.

The first section, Want, examines the nature of value and desire. Want is about what things are worth, what we imagine theyre worth, and whether theres any difference. When you want something, you imagine that its valuable, and the opposite is also true. When the Dutch bought the island of Manhattan for beads, it was the beginning of an epic going-out-of-business sale for the Algonquin. But were the Native Americans completely defrauded, or did they make a better bargain than we think? Whats a stone worth? What makes a stone a jewel, and what makes a jewel priceless? And what does that diamond on your finger have to do with the GI Bill? Each of the accounts in these first three chapters examines how we determine, create, and sometimes imagine value, and how our collective story has been shaped by those valuations.

The second section, Take, is about the corrosive human tendency to covet. It explores what happens when people want something they cant have. This section links several major historical events to desires deniedconsequences that, in some cases, reverberate across centuries: Did Marie Antoinette lose her head over a diamond necklace? Did the French Revolution start because of a coveted piece of jewelry? How did two sisters argument over a valuable pearl in England almost five hundred years ago help draw the map of the modern Middle East? One empire falls, another empire rises, all because of the inherent human weakness for pretty things. Take is about what we want, why we want, and how far well go to get it.

The last section, Have, isnt about war or destruction. On the contrary, its about creation. In Have, we look at some of the more constructive consequences of our ongoing, obsessive love affair with beautiful things. In this section, well meet a noodle maker whose desire to see every woman on the planet wear a string of pearls saved Japanese culture from complete oblivion and helped transform the tiny island into a global economic superpower. Well also meet a European lady who redefined manliness and helped reinvent modern warfare in the processall with a single fashion statement.

The end of one story is only ever the beginning of another. Have is about what happens when we get what we want, and the incredible things that happen along the way.

The history of the world is the history of desire. This is an examination of that history.

Its the story of desire, and its ability to change the world.

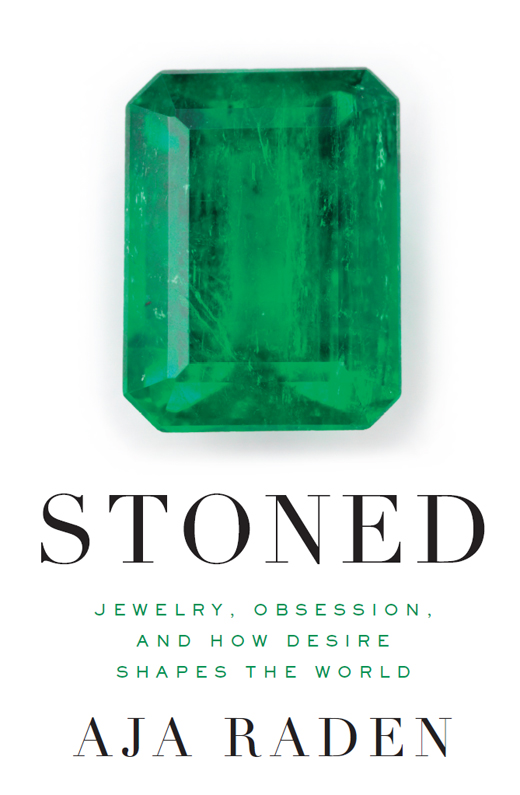

Whats a stone worth? Well, it depends on the stone, obviously.

The real question is: What are our criteria for measuring?

How do we gauge a stones value? By its beauty? Its certainly a factor, but only sometimes. Besides, it leads us right back to the question of criteria: How do we accurately judge a stones beauty? Beauty is important, but terribly subjective.

Size matters, but only once absolute value has been established. A large ruby is worth more than a small ruby. But then, a small ruby is worth more than an enormous marble floor, so size certainly isnt definitive. The same holds true for quality: A flawless quartz is still just, well... quartz.

So whats a stone worth? What makes a stone a jewel? What makes a jewel priceless?

The answer can, perhaps unsurprisingly, be found in a more general examination of the fluctuating value of physical resources like corn, barley, rice, and crude oil. What makes the value of these resources skyrocket? Scarcity. And what makes their value plummet? Oversaturationwhen the supply of the resource outpaces the demand.

The same is true for a stone. Ultimately, its not beauty that determines its valuenor is it size or quality, though each of these factors is important. It is a question of rarity. Its the extremes one must go to to obtain a stone. Its that heady feeling that you have something no one elseor very few other peoplehave.

The problem with quartz is that its just so common. Value comes from perceived scarcity, and the reverse is also true. As soon as a thing becomes too accessible, it loses its luster. After all, if you