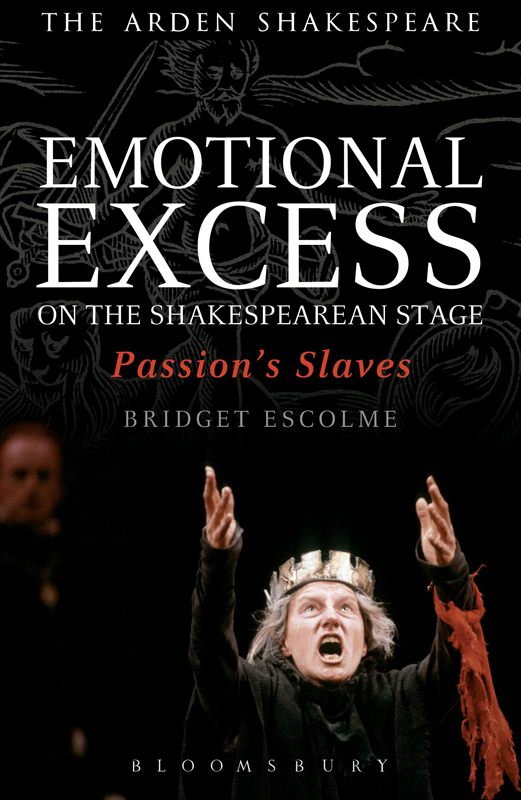

EMOTIONAL EXCESS ON

THE SHAKESPEAREAN

STAGE: PASSIONS SLAVES

To Gary Willis.

And moreover what can be sweeter to our thoughts than the image of a true and constant love , which we are assured our friend doth bear us? What happiness to have a friend to whom we may safely open our heart, and trust him with our most important secrets, without apprehension of his conscience, or any doubt of his fidelity? What content to have a friend whose discourse sweetens our cares? Whose counsels disperse our fears? Whose conversation charms our griefs? Whose circumspection assures our fortunes, and whose only presence fills us with joy and content?

Nicholas Coeffeteau, 1621

EMOTIONAL

EXCESS ON THE

SHAKESPEAREAN

STAGE: PASSIONS

SLAVES

BRIDGET ESCOLME

CONTENTS

This project would not have been possible without the help, encouragement and ideas of many people and organizations. I am extremely grateful to colleagues in the Department of Drama at Queen Mary University of London, particularly to Jen Harvie, Maria Delgado and Nicholas Ridout, who have given invaluable advice and stimulating conversation in their capacities as Directors of Research, and as friends. Nick Ridout played a particularly important role in helping me to know and understand what this book needed to be. I would also like to thank Michle Barrett, Head of English and Drama at Queen Mary, who supported me in my application for a period of research leave to complete the project, all of the School administrative team, particularly Jenny Gault and Beverly Stewart, without whose help with other aspects of my job this book would never have been completed, and Sally Mitchell and the Thinking Writing team for the wonderful Queen Mary Writing Retreats. Many thanks too to Paul Heritage and Peoples Palace Projects.

Many thanks also to all at Arden Shakespeare, particularly Margaret Bartley, Emily Hockley and Claire Cooper.

The work of a great many theatre practitioners actors, directors and designers is at the heart of this book; I would like to thank and acknowledge the work of all referenced in what follows and to mention here those who have given up their valuable time to talk or write to me in recent years Jane Collins, Dominic Dromgoole, Peter Farley, Sunil Shanbag, Roxana Silbert. The help and stimulation of conversations with countless friends and colleagues must also be acknowledged; some of those I mention here will already understand the help and stimulation they have given; others may not realize the influence they have had. They include Frances Babbage, Bobby Baker, Roberta Barker, Christian Billing, Warren Boutcher, Christie Carson, Ralph Cohen, Rob Conkie, Pavel Drbek, Sarah Dustagheer, Indira Ghose, Bret Jones, Farah Karim-Cooper, Eric Langley, Clare McManus, Lucy Munro, Marcus Nevitt, Stuart Hampton-Reeves, Peter Holland, Paul Prescott, Carol Rutter, Richard Schoch, Catherine Silverstone, Kim Solga, Tiffany Stern, Christine Twite, Tiffany Watt-Smith, Penelope Woods, Jan Wozniak, Zoe Svendsen, and Queen Mary undergraduate students who have taken the class Madness and Theatricality during the past five years.

Material in the book has been stimulated and developed through presentation at a range of conferences, including the International Shakespeare Congress; the Shakespeare Association of America (particularly the panel session Academic Pressure and Theatrical Forms organized by Jeremy Lopez and Paul Menzer at the 2012 meeting); the AHRC Network Isolated Acts and its 2012 conference Confined Spaces: Considering Madness, Psychiatry, and Performance, organized by Anna Harpin. I would also like to thank the librarians and archivists at the National Theatre Archive, the Shakespeares Birthplace Trust and Shakespeares Globe for their help and patience.

Thanks should also go to my mother Hilary Escolme, and my brother John Escolme and his partner Jussi Kalkkinen, for listening and questioning. And lastly my love and thanks to my partner Gary Willis, to whom this book is dedicated and who has not only proof-read it in its entirety but has provided unstinting support and encouragement at the most difficult points in its creation. He had always wondered why writers partners got such profuse thanks in the Acknowledgements, and now he knows.

Bridget Escolme, London 2013.

[] For thou hast been

As one in suffring all, that suffers nothing,

A man that Fortunes buffets and rewards

Hast taen with equal thanks. And blest are those

Whose blood and judgment are so well commeddled

That they are not a pipe for Fortunes finger

To sound what stop she please. Give me that man

That is not passions slave, and I will wear him

In my hearts core, ay, in my heart of heart,

As I do thee.

Shakespeare, Hamlet (3.2.6675)

Prior to this eulogy on Horatios blessed balance of blood and judgement, Hamlet gives his advice to the players, in which he conjures the embarrassing image of a bad actor in a wig, to warn the actors against tear[ing] a passion to tatters (3.2.10) with over-emphatic gestures and too much shouting. In both art and life, then, Hamlet seems to privilege cool judgement over hot passion. The description of Horatio as one in suffering all that suffers nothing suggests a complete detachment from the emotions produced by fortunes buffets and rewards, a stoical paradigm of self-control in the face of the slings and arrows Hamlet has already contemplated in the play (3.1.58). A similar privileging of reason over passion emerges in a range of early modern treatises on the passions. While the apatheia with which Hamlet credits Horatio is regularly dismissed as unnaturally blockish and un-Christianof the unreasoning animal. Whereas today, emotion in Western culture is regarded as an individuating force when exhorted to express yourself it is often emotion one is being asked to express the early modern passions are frequently described as that which makes one less of an individual. The passions are material forces barely under the control of what really makes man human: his sovereign reason. Indeed, the four examples of emotion or emotional affect/effect that head up the chapters of this book anger, laughter, love and grief often appear to the early modern philosophical mindset to sit along a continuum at the far end of which is madness. Anger is a potentially murderous mania; the mad laugh unpredictably and inappropriately; love leads to the sickness of love melancholy; grief is the prime producer of melancholic insanity.

Hamlets ideal of the perfect actor and his paradigm for the perfect, dispassionate friend are not the same. True, in advising the Players against anything so oerdone (3.2.21) as gestural air-sawing and vocal passion-tearing, he uses the imagery of weather in a similar vein to early modern sermons on the restraint of the passions in everyday life. For Thomas Playfere in his sermon on (1595), crying is compared to the weather: too much weeping is like an economically unproductive, physically destructive storm:

The water when it is quiet, and calm, bringeth in all manner of merchandise, but when the sea storms, and roars too much, then the very ships do howl and cry. The air looking clearly, and cheerfully refresheth all things, but weeping too much, that is, raining too much, as in Noahs flood, it drowns the whole world.

In the very torrent, tempest, and, as I may say, the whirlwind of your passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness, insists Hamlet (3.2.58) as he holds forth on the actors craft. However, Hamlet does suggest that this temperance of theatrical expression is somehow to be found in the whirlwind of your passion rather than that there should be no such whirlwind in the theatre, whereas his praise of his friend implies that Horatio has found the state of perfect stoical apatheia , in which misfortune and luck are regarded with equally dispassionate equanimity.