Alan Rickman

on

Jaques

Taken from

SHAKESPEARE ON STAGE

Volume 2

Twelve Leading Actors on Twelve Key Roles

by Julian Curry

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

For Alex and Torren

hoping their lives will be enriched by Shakespeare as mine is

Introduction

Julian Curry

Much of the brilliance of Shakespeare lies in the openness, or ambiguity, of his texts. Whereas a novelist will often describe a character, an action or a scene in the most minute detail, Shakespeare knew that his scenarios would only be fully fleshed out when actors perform them. He was the first writer to create character out of language. Falstaff has an idiosyncratic way of speaking that is quite distinct from Juliet, as she does from Shylock, and he from Lady Macbeth. An actor receives subliminal clues about their character, merely by the way they express themselves.

George Bernard Shaw wrote long prefaces and elaborate stage directions; his texts are littered with instructions to actors and directors as to how his plays should be done. This can be helpful, but as often as not its limiting, even annoying. Shakespeare, conversely, wrote hardly any stage directions. The best known is Exit, pursued by a bear in The Winters Tale which incidentally is far from proscriptive: is some unfortunate actor bundled into a bear costume? Or is the bear surreal, an effect of sound and lighting? Directors have carte blanche. The only solution rarely adopted is to put a live bear on stage. On occasion Shakespeare does give a precise indication of stage business. In the courtroom scene of The Merchant of Venice, Gratiano says: Not on thy sole but on thy soul, harsh Jew, / Thou makst thy knife keen [4.1]. Then the actor playing Shylock understands that he should take out his knife and sharpen it on the sole of his shoe. Other stage directions take the form of implicit but less precise suggestions. When Hamlet says to Osric, Put your bonnet to his right use; tis for the head [5.2], the actor playing Osric knows one thing for sure: his hat is not on his head. How else he is using it is up to him.

There are times when the actor may decide to do the opposite of what the text seems to indicate. For instance, when King Lear exits saying to Goneril andRegan, You think Ill weep? No, Ill not weep... this heart / Shall break into a hundred thousand flaws / Or ere Ill weep [2.4], the suggestion appears to be that the actor will remain dry-eyed. Ian McKellen immediately burst into convulsive sobs. I found this very moving.

Shakespeare doesnt tell his actors how to play their parts; he gives hints but leaves the decisions up to them. My interest in writing this book, and the companion volume that preceded it, is the myriad options available to performers of Shakespeares texts, and the choices they make. Theatre is written on the wind. Even the most brilliant performances exist only in the moment, and will endure nowhere but in the memories of those present. Actors are notoriously reluctant to define and discuss how they act, but luckily they are often willing to talk about their past performances.

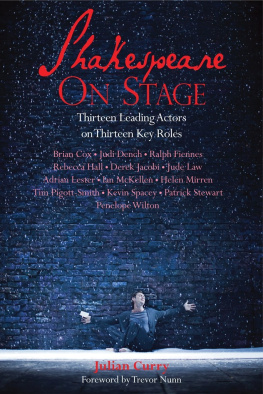

In 2011, the first volume of Shakespeare On Stage found itself on a shortlist of nominees for the annual Theatre Book Prize. It focuses on thirteen of Shakespeares leading roles, therefore covering roughly a third of his plays. This left plenty of uncharted territory. I was delighted when Nick Hern Books agreed that we should continue the voyage of discovery.

As with the earlier volume, my guiding principle was to approach excellent actors who had played leading roles in memorable Shakespearean productions, and to ask them if theyd be willing to reveal if not how they acted, at least what they did. I also wanted to know how the show was set, what they wore, and what went on around them. Having been lifelong in the business, many of my intended targets were friends who were easily accessible, and most generous with their time.

Preparing for each encounter was a labour of love. Of necessity it involved a thorough refresher course, going back to the plays and spending long hours with nose in text. I also read critical studies and pestered archivists for back copies of reviews. I was determined to approach the interviews as well briefed as possible, in order to frame productive questions. At times it felt like the work of a barrister. The difference is that whereas a barristers questions are designed to steer the witness towards a desired answer, mine were simply intended to get juices flowing and tongues wagging. I concentrated on mechanics rather than theory. As far possible I made the question What did you do? rather than How did you do it?

The conversations were tape-recorded, usually at the actors home. I followed, as closely as was practicable, the following sequence: (1) Put the performance in the context of its time and place, director and designer. (2) General questions about the production and the character. (3) Specific questions about the performance, working through the play from start to finish. (4) Summing up.

Shakespeare on Stage: Volume 2 is an account of twelve performances, by the actors who gave them. Each interview focuses on a single performance, and the production in which it featured. They span fifty years, from Eileen Atkinss Viola in 1961 to Patrick Stewarts Shylock in 2011. What they have in common is a uniquely personal account of a creative process. Ive been delighted by the frequent departures from lazy assumption. For instance, Sara Kestelman describes A Midsummer Nights Dream set in an immaculate white box, devoid of all vegetation, and of infants with wings pretending to be fairies. Simon Russell Beale, who looks anything but lean and hungry, was triumphantly cast as Cassius. Patrick Stewarts Shylock ruled over a business empire set in Las Vegas. Ian McKellen repeatedly questions the assumption that King Lear goes mad, just as Alan Rickman finds the adjective melancholy inadequate to describe Jaques. Im not aware of any other continuities or recurring themes. On the contrary, each one quite naturally occupies its own territory, and Im happy with that. It also seems that, as a by-product, the actors have in fact revealed a great deal about themselves and their own working methods. As such, I hope the reader will enjoy the range and diversity of responses, and that it will be of interest to other actors, students and theatregoers alike.

This is the introduction to Shakespeare on Stage: Volume 2; the volume in which this interview first appears.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the Society of Authors for a very generous grant which bought me time to interview the subjects, and to write this book; and to Sue Webb, Mary Chater, Matt Applewhite and Nick Hern for their invaluable support and encouragement. Finally, and most especially, thanks to all of the actors who kindly gave their time to be interviewed.

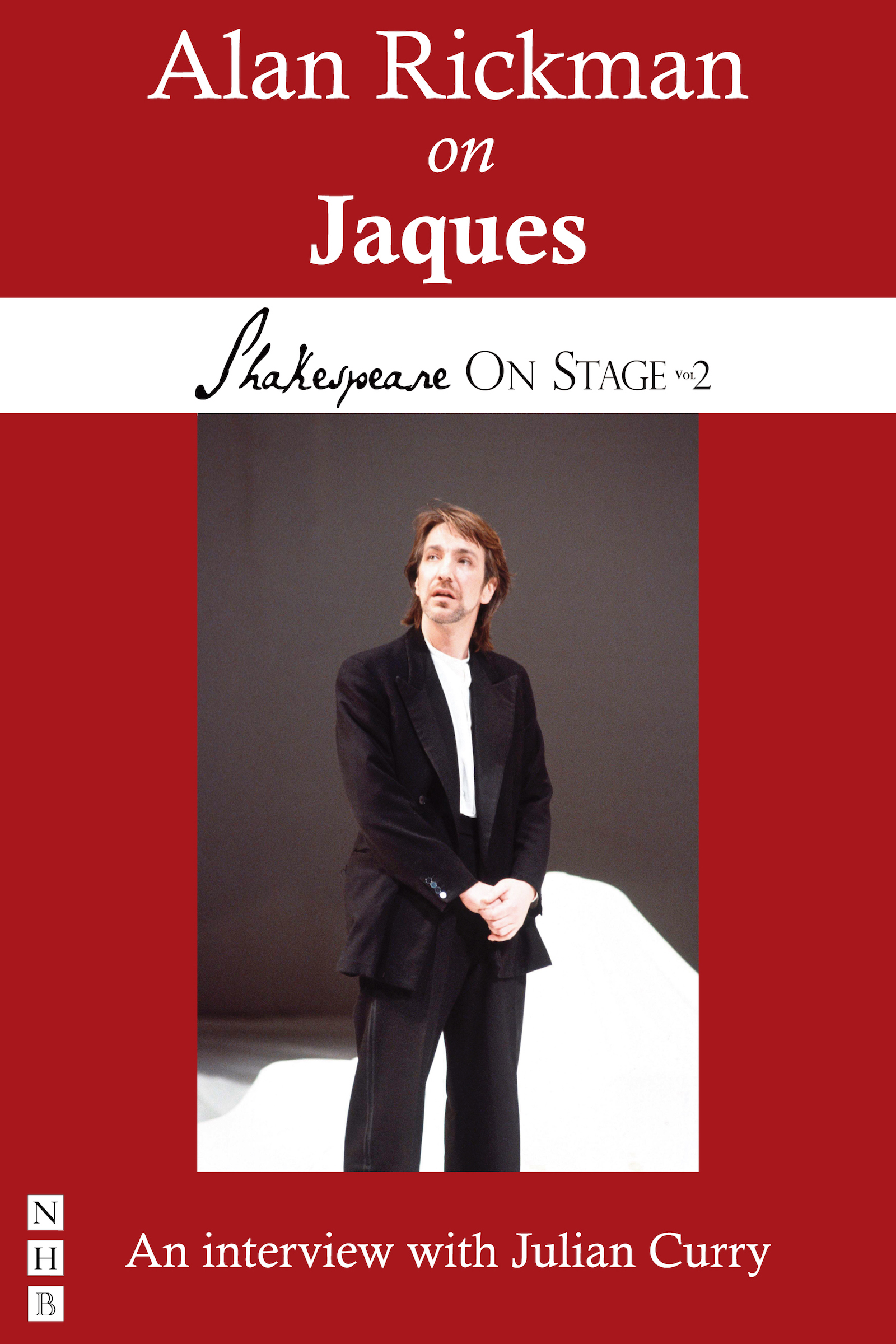

Alan Rickman

on

Jaques

As You Like It (1600)

Royal Shakespeare Company Opened at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on 23 April 1985

Directed by Adrian Noble

Designed by Bob Crowley With Nicky Henson as Touchstone, Hilton McRae as Orlando, Fiona Shaw as Celia, and Juliet Stevenson as Rosalind