Helen Mirren

on

Cleopatra

Taken from

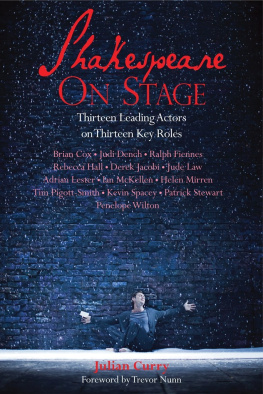

SHAKESPEARE ON STAGE

Thirteen Leading Actors on Thirteen Key Roles

by Julian Curry

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Helen Mirren

on

Cleopatra

Antony and Cleopatra (16067)

National Youth Theatre

Opened at the Old Vic Theatre, London, in September 1965 Directed by Michael Croft, Designed by Christopher Lawrence With Clive Emsley as Enobarbus, Timothy Meats as Octavius Caesar, and John Nightingale as Mark Antony

Royal Shakespeare Company

Opened at The Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, on 13 October 1982 Directed by Adrian Noble, Designed by Nadine Baylis With Sorcha Cusack as Charmian, Michael Gambon as Mark Antony, Jonathan Hyde as Octavius Caesar, and Bob Peck as Enobarbus

National Theatre (pictured above)

Opened at the Olivier Theatre, London, on 20 October 1998 Directed by Sean Mathias, Designed by Tim Hatley With Finbar Lynch as Enobarbus, Trevyn McDowell as Charmian, Alan Rickman as Mark Antony, and Samuel West as Octavius Caesar

Antony and Cleopatra is Shakespeares late tragedy, first performed circa 1607. The play is in part a sequel to Julius Caesar, charting the break-up of the AntonyOctaviusLepidus triumvirate that ruled Rome following Caesars assassination. However, the main focus is on Cleopatras Egyptian court, where the central pair act out their tempestuous relationship. Admirers of Antony and Cleopatra praise its sublimity, its rich characterisation and gorgeous language. Shakespeare, typically, shows the mighty conflict between Egypt and Rome revolving around the relationship of two lovers at the heart of the action. Despite its epic plot, much of the play is domestic in scale. With their all-too-human tiffs and hysterics, the middle-aged couple represent a touching fragility at the centre of world politics.

Cleopatra is one of Shakespeares most complex heroines. She has political nous, charisma, and an indomitable will. Her self-obsessed histrionics can provoke an audience to laughter, even to scorn. Yet both she and Mark Antony carry tragic grandeur. The doting Antony tells her she is a woman Whom everything becomes to chide, to laugh, / To weep [1.1]. She is described as a lustful gypsy, a slave and a whore. She is resented by Rome as the enchantress who has made Antony neglect his duties and become the noble ruin of her magic [3.10]. She can, as Enobarbus describes [2.2], be awe-inspiring. When Cleopatra takes the stage she does so as a diva, likely to elevate any colour of emotion to the most dramatic and captivating level. At the end of the play the victorious Octavius Caesar intends to lead her in triumph through Rome. Her determination to thwart him by applying a serpent to her breast is perfectly in character.

I first worked with Helen Mirren when she was starting out at the RSC, and later as her Cardinal brother in The Duchess of Malfi. She has progressed spectacularly from 1960s free spirit to Oscar-winning Dame of the British Empire. Every other interview in this book focuses on a specific production. But in Helens case it was more open-ended, as she has played Cleopatra three times. The last occasion was at the National Theatre opposite Alan Rickman. This was considered dream casting and the show sold out before it opened. But, strangely, the production didnt amount to the sum of its parts. They were described by one critic as resembling a pair of glumly non-mating pandas at London Zoo, coaxed to do their duty. So it didnt seem a good idea to dwell on that version. Nonetheless, Helen is superb casting as Cleopatra, and its impossible to imagine anyone better suited to discuss the part. We met in August 2009 in her dressing room at the National Theatre during her run as Phaedra.

Julian Curry: Youve played Cleopatra three times. First for the National Youth Theatre, I think, when you were nineteen years old, fresh out of convent school.

Helen Mirren: Well, I was at college already. But yes, pretty soon after school.

Its a wonderful part, one of the great tragic roles. Shes also dead sexy and shes funny, shes ruthless and vulnerable. It must be a treat to play.

Not necessarily because Antony and Cleopatra is, as someone called it, a sprawling whore of a play. Its a great role in not a great play. Its a flawed play with some very great roles in it, Cleopatra being one, and Enobarbus being another. Antonys not such a good role. Octavius Caesar is another great role. But its very, very difficult to make the play work. So its not a great role in a great play, which is the ideal scenario.

Somebody wrote about your performance All the shifts from teasing tart to imperial rage, she makes clear, are evasions of the truth. Does that ring a bell with you?

In terms of the performance?

Yes, what Cleopatras playing at.

I think there are three different Cleopatras. Theres the Cleopatra of real history, theres the Cleopatra of Roman history, and then theres the Cleopatra of Shakespeare. I was interested in marrying up the Cleopatra of real history with Shakespeares Cleopatra. However, Shakespeares Cleopatra does seem to owe a lot to the Roman version of history, probably more than to the absolute truth of who she was. But of course the real Cleopatra is so much more interesting than either Shakespeares or the Roman Cleopatra. So I was always looking for ways to bring the real person into this rather fake person that Shakespeare presents.

He certainly seems to focus on the whore, the strumpet, Antonys Egyptian dish [2.6]. These things keep being said about Cleopatra. Whereas in fact she was extremely erudite, wasnt she, and a very astute politician.

Yes, enormously. And not very beautiful at all, but incredibly clever. My sense from history was that in order to save Egypt she had to suck up to Rome, because she knew that Rome could annihilate Egypt, and had its eyes on Egypt because it was the breadbasket of the East. It was incredibly wealthy, especially I think in agricultural terms. So Rome wanted it, they wanted control of it. To try and maintain both her own power and Egypts autonomy, I guess, she knew she had to kowtow to Rome to a certain extent, and seduce Rome not necessarily sexually, but in every way possible. That was my sense about her. So she uses Rome, she used Julius Caesar as far as she possibly could, and then she used Mark Antony as far as she possibly could.

Enobarbuss famous speech The barge she sat in [2.2] describes an amazing piece of stage management, it seems an absolutely dazzling set-up that she created.

And that she did do.

But that was before she first met Antony.

Yes.

So she set out to seduce him without knowing the man?

No, its much more than that, much more than a seduction. It was a power struggle, that was the way I saw it. The whole point of that particular episode was Antony had gone to the marketplace or wherever. Hed turned up as the big powerful guy from Rome, to have a huge public meeting, expecting everyone to be there, and they didnt turn up because Cleopatra put on a parallel performance and said Guess who is the most powerful person in this country? Its not you, its me. Im the person that people want to see, not you. So it seemed to me, that was much more to do with power than seduction. And then of course, the power play continued because she I dont like the word seduce but I cant think of a different one the following evening she showed her unbelievable wealth. She put on this incredible evening for Antony and his crew. And that also seems to be historically accurate.