QUEENS AND MISTRESSES OF RENAISSANCE FRANCE

Q UEENS AND MISTRESSES OF RENAISSANCE FRANCE

Kathleen Wellman

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven & London

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of William McKean Brown.

Copyright 2013 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

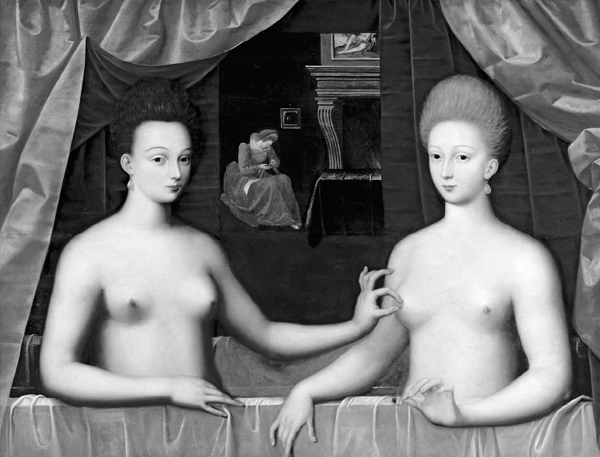

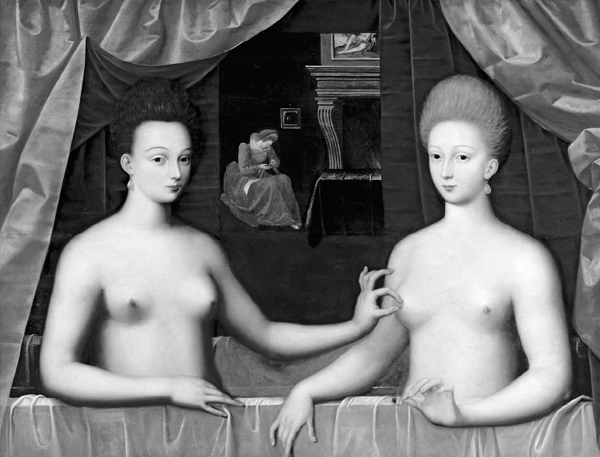

: Gabrielle dEstres and her sister, the duchess of Villars. Fontainebleau school, late sixteenth century. Louvre/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wellman, Kathleen Anne, 1951

Queens and mistresses of Renaissance France / Kathleen Wellman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-17885-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. FranceKings and rulersBiography. 2. QueensFranceBiography. 3. MistressesFranceBiography. 4. FranceHistory15th century. 5. FranceHistory16th century. 6. RenaissanceFrance. I. Title.

DC112.A1W45 2013

.0209252dc23

2012037490

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my children, Elizabeth and Matthew

C ONTENTS

P REFACE

This book grew out of my experiences as co-director of the SMU-in-Paris summer program for more than a decade. Students who knew little about the French Renaissance were fascinated by the prominent figures who lived in chateaux of the Loire Valley and especially intrigued by the long-standing royal mnage trois of Henry II, his wife, Catherine de Medici, and his mistress, Diane de Poitiers. As I considered how I might use that relationship to present this period, I discovered that queens and mistresses were much more central to the Renaissance than histories of the period acknowledge. The Renaissance court, focused on the person of the monarch, fused the familial and the political. As a result, it offered women of talent and determination opportunities to assume political and cultural roles through their intimate association with kings. Less rigidly organized than it would become under the absolutist kings of the seventeenth century, the Renaissance court proved more amenable to the influence of royal women. These queens and mistresses were also subjects and patrons of artists and writers, and two of themMarguerite dAngoulme and Marguerite de Valoiswere important writers. They left a legacy in the paintings, histories, memoirs, legends, and myths they inspired, promoted, or even produced. This book thus makes queens and mistresses central to a narrative of the French Renaissance by exploring their roles in politics and culture from the designation of Agns Sorel as the first official mistress in 1444 to the death in 1599 of Gabrielle dEstres, the mistress Henry IV planned to marry.

These women were not simply important to their time; they have had equally rich posthumous lives. They are important sites of memory, as explored in Pierre Noras important collection of essays on the places (construed broadly) where national memories coalesce. Each woman treated in this book has been used subsequently in a rich variety of ways: as a foil for the king or to elevate or condemn him; to fault the monarchy as a corrupt form of government or, antithetically, to praise it as an era of romance and grace; to argue against womens political activities or, very recently, to assert their importance to French culture. Ultimately, these women have played roles in defining the history and national character of France.

All of the women central to this project have been treated by historians, biographers, and polemicists from the sixteenth century to the present in French. They are prominent in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century primary sources, featured in poetry, memoirs, and political writings. Their stories became significant in political writings; French writers have used these women to take a position for or against the republic, the monarchy, or the Church. They occupy a place in Renaissance scholarship and modern popular history. Royal figures have attracted a resurgence of popular interest in France, just as they have in America. Biography too has enjoyed a revival in France as a kind of historical writing with widespread appeal. Most of these women have been treated in French popular biographies but are largely unfamiliar outside France, especially as compared to their better-known contemporariesHenry VIIIs six wives. But French queens and mistresses generally lived longer and were more politically active and culturally influential. Despite their prominence in their day, they are neither central to the conventional understanding of French history nor extensively treated in English-language texts, with two notable exceptions: Catherine de Medicis political career and Marguerite dAngoulmes literary work.

The French Renaissance has, however, been a particularly fruitful period for both English-language scholars and their French counterparts, capturing the attention of accomplished and prolific historians such as Ivan Cloulas, Denis Crouzet, and R. J. Knecht. Several women featured here have attracted French scholars. Eliane Viennots editions of Marguerite de Valoiss works and biography of her, and Crouzet and Thierry Wanegffelens works on Catherine de Medici are especially significant. French scholars Didier Le Fur, Anne-Marie Lecoq, and Nicole Hochner have studied the construction of the myths of Anne of Brittany, Francis I, and Louis XII, respectively. Art historians and literary scholars, including Cynthia Brown, Elizabeth LEstrange, and Colette Winn, among others, have focused on the contributions of royal women to French patrimony as patrons and thus purveyors of images of both women and the monarchy. These works attest to the vibrancy of this field. This book is greatly indebted to recent studies of these women, in particular, and the culture of the Renaissance, womens history, and art history. I have also relied extensively on primary sourcessome written by the women themselves, others by contemporaries commenting on them, the monarchy, or the culture of the day, and others writing later to define their histories, legends, and myths.

Mistress and queen, positions seemingly anachronistic in modern democratic culture, remain relevant to our more egalitarian political culture. We too have a culture enamored of celebrity, where young, beautiful women marry or consort with older, powerful, wealthy men. We too wonder about the influence women might exert in politics through pillow talk. We, like men and women of the Renaissance, find the political influence of women, who have that influence only because of their personal relationships with powerful men, both intriguing and disturbing.

Like modern royalty or celebrities, Renaissance queens had access to funds and were able to define themselves through available media as politically important and culturally relevant, as complements to their husbands, and as integrally linked with the good of the country. All evidence to the contrary, they embody for some modern women expectations of an idyllic marriage and fairy-tale ending to a courtship. The royal mistress who attained immediate celebrity and high status has modern resonance. Lavish gifts to her often translated into great inheritable wealth for her family. Her precipitous rise gave her a hold on the popular imagination perhaps akin to that of the Hollywood actress: The public both wanted to know everything about her and, rather perversely, assumed that celebrity reflected virtue or merit. The modern allure of royalty or Hollywood celebrities has something in common with the Renaissance appreciation of queens and mistresses. The roles of queen and mistress were malleable enough to allow women to define them in dramatically different ways. Like an American First Lady, they had opportunities by virtue of their position. Their use of the position not only shaped their lives and influenced their historical reputations but also separated the great or influential queens or mistresses from those who simply held a distinctive status.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).