INTRODUCTION

This do-it-yourself Workshop Manual has been specially written for the owner who wishes to maintain his vehicle in first class condition and to carry out the bulk of his own servicing and repairs. Considerable savings on garage charges can be made, and one can drive in safety and confidence knowing the work has been done properly.

Comprehensive step-by-step instructions and illustrations are given on most dismantling, overhauling and assembling operations. Certain assemblies require the use of expensive special tools, the purchase of which would be unjustified. In these cases information is included but the reader is recommended to hand the unit to the agent for attention.

Throughout the Manual hints and tips are included which will be found invaluable, and there is an easy to follow fault diagnosis at the end of each chapter.

Whilst every care has been taken to ensure correctness of information it is obviously not possible to guarantee complete freedom from errors or omissions or to accept liability arising from such errors or omissions.

Instructions may refer to the righthand or lefthand sides of the vehicle or the components. These are the same as the righthand or lefthand of an observer standing behind the vehicle and looking forward.

OWM 827

ISBN 9781870642590

First Edition 1970

Reprinted 1972, 1976

Second Edition, fully revised 1979

Reprinted 1989

Brooklands Edition 1992

Brooklands Books Ltd. 1992 and 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Brooklands Books Ltd.

Whilst every care has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author, nor the publisher can accept any liability for the loss, damage or injury caused by errors in, or omissions from the information given.

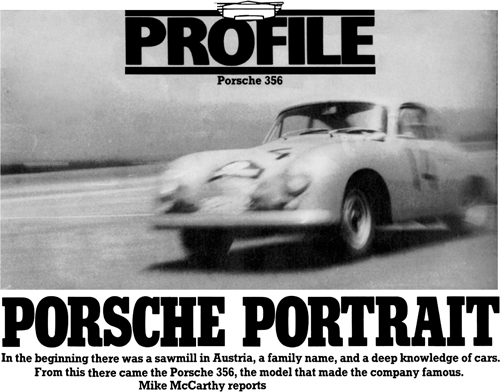

The number 356 is hardly memorable. It doesnt roll off the tongue, it doesnt sound poetic, it could be the most anonymous number you could think of between 1 and 1000. Yet to motoring enthusiasts generally, and Porscheophiles in particular, those three digits have a very special significance. They were applied to one of the greatest sports cars the world has ever seen.

Its origins are quite prosaic. It simply meant Porsche project Type 356, a design for a small, light tourer based on VW Beetle mechanics. But it was the culmination of the lifetimes work of one man, a genius called Ferdinand Porsche, who would not live to see the 356 and its successors cover themselves with glory.

After the war the Porsche works at Gmnd had taken on any and every job they could, first under Ferdinands daughter, Louise Pich, then under his son Ferry.

By 1947 however, the company had grown, and an idea that had been brooding at the back of Ferrys mind became more concrete: Porsche would build their own car, bearing their own name. On June 11, 1947, project Type 356 was officially born.

Not unnaturally, proprietary parts had to be used the company was too small to invest in tooling to manufacture such costly items as engines, transmissons and suspension. And, since the car they knew best (more than anyone else in fact, for had they not designed and developed it?) had miraculously, and against all predictions, gone into production, it was only natural that it would form the basis of the Porsche it was, of course, the VW Beetle.

The first prototype was very much a one-off. It was a three (abreast) seater, open, with a space-frame chassis and uniquely a mid-engine configuration, with the power unit between cockpit and back axle. This was a modified VW air-cooled flat-four with bigger valves and ports and a daringly high (considering octane ratings of the day) compression ratio of 7.0:1 to give between 35 and 40bhp, a vast increase on the standard offering of 25bhp. VW independent suspension, by torsion bars all round, was fitted, as was a standard VW gearbox turned back to front. Covering all the mechanics was a very sleek aluminium body, with minimal ornamentation or excressences, designed by a name famous in Porsche folklore, Erwin Kommenda. Across the nose the name PORSCHE was spelt out in distinctive, square lettering of a form that is still with us.

Concurrent with the original prototype, another was being constructed which was in fact the definitive 356. It was a coup, and it differed radically from the open car. For a start, the engine was in the normal VW position, overhung behind the rear axle. Then the chassis was constructed of sheet steel fabrications, not tubes. And it was, of course, a hard top, visually almost identical from the waist down to the open car. Kommendas shape was, once again, utterly smooth, full of wide radius curves, with nary a straight line in sight. Today such curves are accepted as the norm for good aerodynamics (cf the Audi 100/200 and the Ford Sierra): in the late forties opinions varied from ugly to sensational, but there was no doubting the shapes effectiveness. In what must have been one of the first experiments in aerodynamics, wool tufts were attached to Porsches demonstrator to check airflow, with very satisfactory results.

From these unlikely beginnings, a legend would grow. The 356 is not one but a multitude of models, some, such as the Speedster and Carrera, so different as to be regarded as unique in their own right, and requiring separate treatment. Throughout its 18-year lifespan the 356 underwent a continuous, constant, bewildering process of development, refinement and proliferation, recounted under Production history.

There were concrete constants. The name, the basic configuration with an air-cooled flat four in the tail, independent torsion-bar suspension, efficient streamlined bodywork. Then there were the less concrete constants. The insistence on superb quality: a performance out of all proportion to engine capacity; cost they were never cheap in the sense that the Austin Healey or Triumph TR2 were, particularly in the UK; Porsches determination to go its own way and not just follow fashion; but above all, perhaps, was the 356s addictiveness. Speak to a 356 afficianado and he will brook no criticisms. Quirky handling? Never! All other cars are boring by comparison.

Few who have ever driven a 356 in anything like reasonable condition can come away unimpressed. For a fifties car it hides its age remarkably. The steering is light, direct, and so responsive. The ride is astonishing. The feeling of tautness, of rigidity, even in the open models, is outstanding. Here is a highly civilised, highly enjoyable, jewel of a machine, quite unlike anything else of its own period or any other.

If there is one facet of the car which creates more controversy than any other (looks apart) it is the handling in extremis. Primitive swing axles at the rear plus an engine in the tail add up to oversteer, no matter how you look at it (which is why, in later models, Porsche kept adding understeer to the chagrin of enthusiasts). There is even a phrase used by Porscheophiles to describe the handling of the early cars: wischen, the German for wiping, a graphic description of the cars cornering attitudes. It was counteracted by sger, or sawing, which is what the driver had to do to stop ends swapping. If you did over-step the mark you performed what Denis Jenkinson, an arch-enthusiast if ever there was one, calls the ground-level flick-roll, to the detriment of car and driver. The world, though, is divided into two species: those who revelled in such antics (flick-roll apart!) and those who were frightened by it. What the latter didnt realise was that the speeds at which the 356 became uncontrollable were usually considerably higher than those at which more conventional machines would long since have exited stage left!

![Trade Trade Porsche 356 owners workshop manual: [1957-1965]](/uploads/posts/book/237774/thumbs/trade-trade-porsche-356-owners-workshop-manual.jpg)