Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

APPROPRIATELY, FOR MARK

When doctors, nurses, and other health-care professionals write about their experiences, they face a particular challenge in how to describe their experiences with patients. On the one hand, I believe that it is critically important to tell the story of the Bong County Ebola Treatment Unit, in no small part so that readers who have not been to Africa can know something about how Ebola affected real people there. On the other hand, patients are entitled to privacy, and should not have to worry about whether their doctor will inappropriately expose their lives for the world to see.

I have tried to walk this fine line by leaving out of this story identifying details about the lives of the patients described in the following pages. In many cases, I have provided pseudonyms and altered superficial aspects of patients lives so that they are not identifiable. Patients whom I describe from, say, Nimba County may have actually come from Lofa or Margibi counties instead; a man with a daughter may have actually had a son; and so on.

However, a number of the patients from the Bong County ETU had previously been interviewed by local Liberian media as well as a variety of international news organizations. I have not changed the names of those patients who had consented to such interviews, and also of some others whose names were already publicly known. Even as to those, however, I have avoided adding further details about their stays in the ETU beyond what is already a matter of public record.

How I wish I was in a dream, and Im waking up, and I discover, Oh, thats a dream.

Joshua Blahyi, formerly known as General Butt Naked, circa 2013

I think were never going to agree, for our disagreement is one between sensibilities. Id designate them as, on the one hand, the ironic and ambiguous (or even the tragic, if you like), and, on the other, the certain. The one complicates problems, leaving them messier than before and making you feel terrible. The other solves problems and cleans up the place, making you feel tidy and satisfied. Id call the one sensibility the literary-artistic-historical; Id call the other the social-scientific-political. To expect them to agree, or even to perceive the same data, would be expecting too much.

Paul Fussell, Thank God for the Atom Bomb

Not long after I submitted the first draft of this book to St. Martins Press, I found myself sitting in a lecture hall at the medical school listening to a group of students who had won prizes for writing in medicine. Over the next hour and change, the prizewinning students read aloud their essays or poems to the crowd. For the most part, they told stories about the patients whom they encountered as they began their formal training. The patients one meets at the beginning of training tend to form an indelible impression, and these students wanted to preserve those memories for posterity.

After listening to a few readings, I was struck by the similarities among the pieces, even though the writing styles differed from one another, sometimes starkly so. Virtually every students musings, whether in verse or prose, were preoccupied with what the process of learning medicine was doing to them as individuals. It was clear they feared losing an essential quality of themselves as the riptide of medical knowledge and the jargon of physicians pulled them away from the shores of some perceived humanity. You could practically hear all of them shout that they didnt want their capacity for caring and empathy to abandon them, dreading that the system was grinding them into soulless automatons as they learned how to reduce their patients lives and hopes and dreams to a few terse lines summarizing their history of present illness and past medical history and culminated in some efficient medical plan. There was a shared poignancy to their laments.

One particular students words caught my ear. The piece was written by a young student doctor named Haley Newman, someone whom I had known peripherally while she was doing her internal medicine rotation. Her essay described her relationship with a veteran who had been given an unexpected diagnosis of a devastating illness, a cancer with which he would have long and unpleasant battles. She had a gift for words and was able to paint a picture with a carefully selected image: His Vietnam Veterans of America hat was always sitting on his bedside table, along with a bag of Lays potato chips and a Snickers bar was but one image that struck me as coming from someone destined to write a weekly column, or a book, on medicine.

Haleys essay was an exercise in enumerating the misgivings that to some extent plague the lives of everyone who takes up the stethoscope as a calling. Regardless of everything dehumanizing in the hospitalthe blue johnnies, the tubes and IV lines, the meals on trays and red help buttonsthese individuals are not just patients, she wrote. They are unique people with powerful stories, and their identities should not be erased by their illnesses. To my ears, her eloquence masks a quiet rage against all the degrading aspects of medicine, a process she can sense is already changing her, hardening her in ways such that she may not even be able to recognize herself a few years hence.

Its even worse than she knows, for some of that learned insensitivity to suffering is pretty much required for us to care for our patients, and it constitutes one of the central paradoxes of being a doctor or nurse. The good news, I want to tell her, is that it really is possible to maintain the human element in medicine, although it takes some conscious effort. The bad news is that one almost never stops fighting this rearguard battle to preserve that element every day of ones professional life, and even the finest physicians will have a career littered with defeats.

These student essays also underscored another feature of how we medical professionals cope with that kind of paradox: We simply bear witness to what happens to our patients. All of the essays told stories of sadness and loss, and that kind of activity continues well beyond medical school. We tell these stories to one another in conference rooms, quick conversations in hallways, longer rap sessions with spouses or friends, and for some of us, in formal writing. They provide our way not only of coping but of reaffirming why we chose the work of caring for total strangers in the first place. Nearly all great literature is an affirmation of humanity, and the act of bearing witness is what the best writers have done for millennia. But doctors stories are our special means by which we can say to the world that the lives of our patients matter and the practice of medicine is essential to humanity. We tell these stories by using the technical language of anatomy and physiology, as we elaborate upon the privileged access we are granted to our patients bodies and, on occasion, souls.

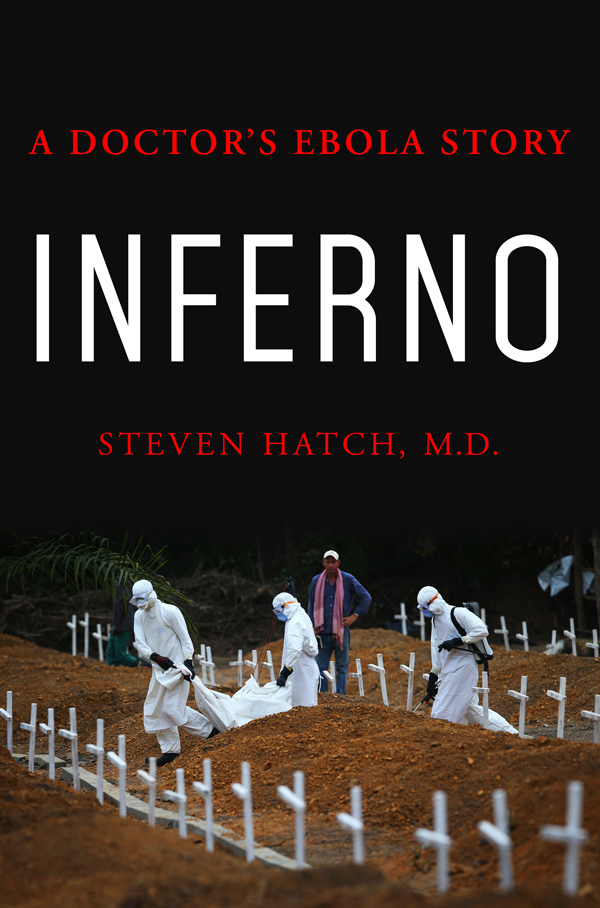

At its core, this book is no different than Haleys essay and those of her classmates whose work illuminated that day; it possesses the same structure, with the same goals in mind. As the title proclaims, Inferno is a doctors story of the Ebola outbreak. It is an attempt to use my experiences as a physician working before, during, and after the West African outbreak of 2014 and 2015 to provide readers with an understanding of something beyond much of the news coverage at the timeespecially the television news, which so greedily chewed up and spat out images of workers in space suits moving alongside dying Africans.