Key Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies

Reality TV, June Deery

Pornography, Rebecca Sullivan and Alan McKee

Pornography

Structures, Agency and Performance

Rebecca Sullivan and Alan McKee

polity

Copyright Rebecca Sullivan and Alan McKee 2015

The right of Rebecca Sullivan and Alan McKee to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2015 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-9484-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

Contents

Guide

Print Page Numbers

Acknowledgements

The authors would jointly like to thank the wonderful staff at Polity who first envisioned this project and gave us unlimited support and freedom to express ourselves. Special thanks to Andrea Drugan, the one who made it all possible. We also extend our gratitude to all the Polity reps with whom we had the pleasure to work: Joe Devanny, Elen Griffiths, Lauren Mulholland, Neil de Cort and Susan Beer. Thanks as well to our book designer, David Gee. Our two peer referees gave thoughtful, supportive feedback that strengthened the final work and gave us renewed confidence in our arguments. We also acknowledge, with deep gratitude and respect, our incredible editorial assistant, Tiffany Sostar. She spent long hours and sleepless nights poring over our manuscript, not only correcting technical faults but also offering sharp insights into pornography activism. A more professional and passionate collaborator we could not have imagined.

I would like to extend personal gratitude to the students at the University of Calgary who have enrolled in my courses on pornography and taught me more about this subject than I think I taught them. The Womens Studies and Feminism Club, Consent Awareness and Sexual Education Club, the Q Centre for Sexual and Gender Diversity, and the Womens Resource Centre have given me the gift of an intellectual and activist community, from which I draw sustenance and courage.

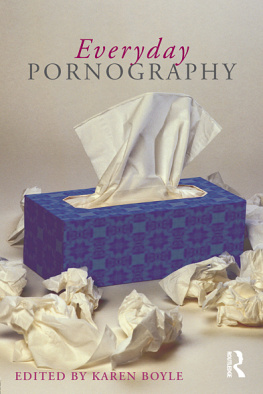

Special thanks to colleagues near and far who have inspired this work and provided support: they include Feona Attwood, Alison Beale, Karen Boyle, Paul Johnson, Catherine Murray, Katharine Sarikakis, Clarissa Smith, Lisa Tzaliki, and Thomas Waugh. Although in many instances our paths cross infrequently and briefly, you have all been a unique part of this journey. I especially want to thank my gracious and generous co-author, Alan McKee, without whom this project may never have been completed. I must also extend an additional thank you to Tiffany Sostar for introducing me to the world of feminist queer pornography and making it possible for me to begin my own discovery of the field. What I once believed impossible has now exceeded my wildest (political) dreams.

Finally, I wake up every day grateful for my loving husband, Bart Beaty, and our amazing son Sebastian. Just because.

Rebecca Sullivan

I would like to thank first of all Professor John Hartley my first and best mentor, and a profound thinker whose democratic approach to culture radically challenges traditional academic thinking. His work has helped to make it possible for downmarket, trashy and vulgar people like me to work in the academy.

The writing-up of this book was made possible by the Creative Industries Faculty at Queensland University of Technology through a Long Professional Development Leave grant. My ten years at QUT were inspiring and exciting and I learned a lot. Thank you to everybody there.

Im profoundly grateful to the colleagues who helped me develop my thinking about culture and sex Rebecca Sullivan (of course), Anne-Frances Watson, Johanna Dore, Christy Collis, Jerry Coleby-Williams, Catharine Lumby, Kath Albury, Brian McNair, Feona Attwood, Clarissa Smith, Emma Jane, Sarah Tarca, Claire Starkey, Anthony Walsh, Clare Moran, Michael Dunne, Sue Grieshbaber, Ben Mathews and Juliet Richters. Any mistakes or eccentricities remain my own.

And finally, I send my love to my husband, Anthony John Spinaze without you I would not be so sane. Thank you.

Alan McKee

Introduction

Pornography and Porn Studies

What is pornography? Who is it produced for, and what sorts of sexualities does it help produce? Why should we study it, and what should be the most urgent issues when we do? These are the questions that frame our analysis of how pornography is conceptualized as a sexual practice, a media form, and a social issue. This is a book about pornography as a concept, one that is charged with numerous political, social, and cultural concerns about gender roles and sexual relationships more generally. As such, we are largely interested in the debates and discourses that circulate about pornography how they are organized, what sorts of assumptions lie behind them, who is most deeply implicated in them. The goal of this book is to situate those debates and discourses within networks of competing gender and sexual politics in globalized cultural systems, and to suggest new frameworks for the understanding of pornography. We treat pornography as an integral part of commercial media industries, national and international regulatory discourses, gendered social structures, and subaltern sexual praxis.

Pornography is notoriously difficult to define, and overburdened with assumptions concerning at the very least gender, sexuality, power, globalization, desire, affect, and labour. Yet that should not allow us to sidestep this demanding task: it is not good enough merely to repeat the famous dictum by United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, I know it when I see it (Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 US 184 (1964)). At stake in the definition of pornography is the recognition that sexual pleasure is a highly contested and politically fraught concept, and that media and popular culture have a long history of perpetuating deep-set gender and sexual inequities and making them appear pleasurable. At the same time, we also appreciate that many of us create and consume media entertainment to enhance our sexual freedoms and pleasure-seeking. In so doing, the boundaries of what can and cannot be seen, spoken, or performed are challenged and redrawn. That is why pornography is such an important concept for anyone concerned with the role of media and popular culture in everyday life. It deserves to be studied in ways that take into consideration its multiple possibilities and in the context of who is making it, who is watching it, and how.

Next page