2017 Random House Trade Paperback Edition

Copyright 1972 by Barbara W. Tuchman

Copyright 1972 by Council on Foreign Relations, Inc., New York

Copyright 1972 by The Associated Press

Notes I through VIII were originally written for and distributed by The Associated Press.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Originally published in the United States by Collier Books in 1972.

Note IX, Friendship with Foreign Devils, is reprinted by permission of Harpers Magazine and appeared in the December 1972 issue.

If Mao Had Come to Washington in 1945: An Essay in Alternatives is reprinted by permission from Foreign Affairs, October 1972.

ISBN 9780812986228

Ebook ISBN 9780812986235

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 72-93468

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Gabrielle Bordwin

Cover photograph: The Granger Collection, New York

v4.1

ep

Contents

A Note on How I Came to China

T HIS IS WHAT I vowed I would never doput ephemeral journalism between the covers of a book. But I was offered a persuasive rationale: that these reports are the outcome not only of a six-week visit but of an interest in the Far East that goes back almost forty years.

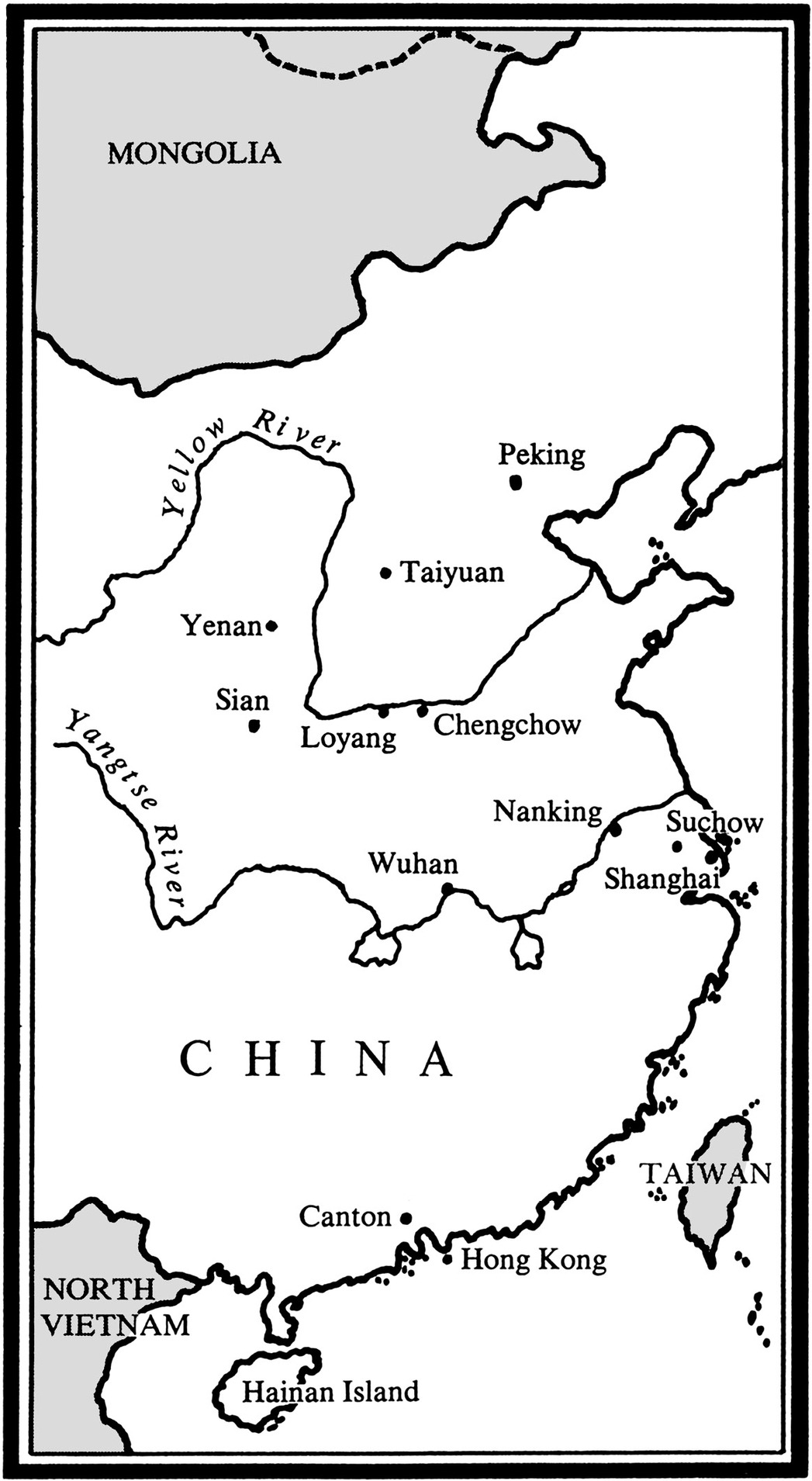

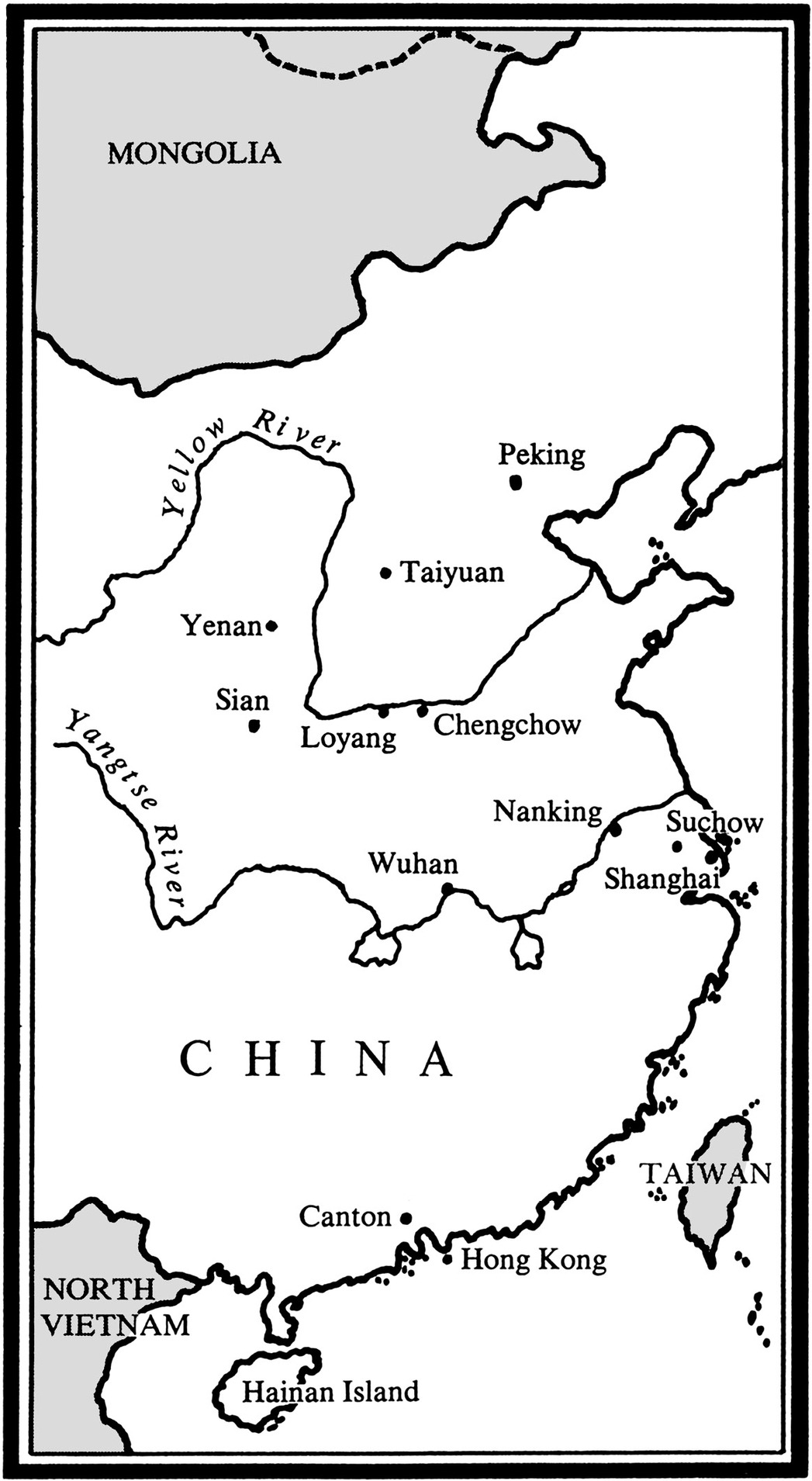

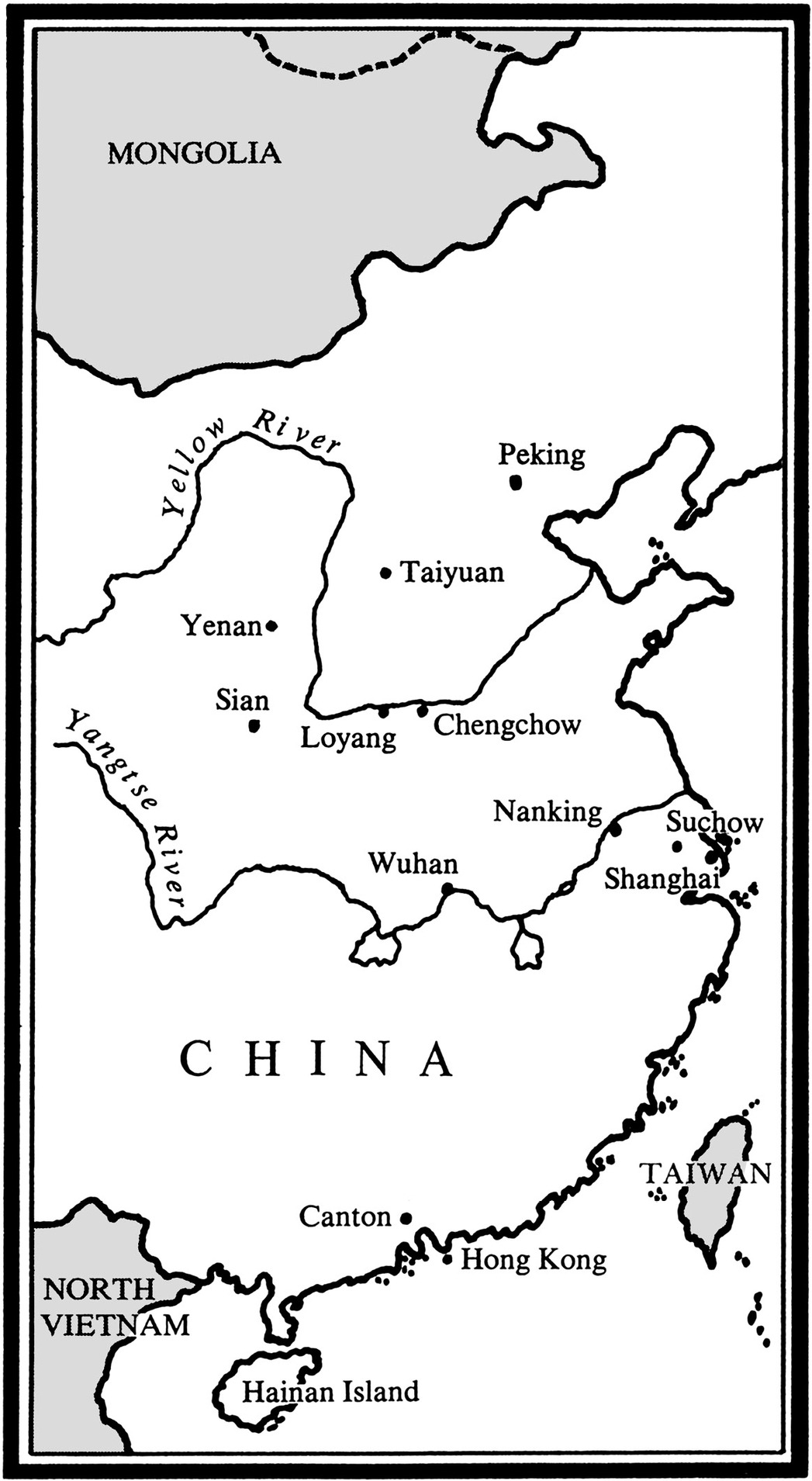

In 1933 on graduating from college, I joined the staff of the American Council of the Institute of Pacific Relations, an international organization representing countries with territory on the Pacific. In October 1934 I went to Tokyo for a years stay to work on a project of the IPR, The Economic Handbook of the Pacific Area. It was the hope of the Institute, by centering the work in Tokyo, to keep contact with and possibly encourage the liberal elements in Japan, but controlling tendencies there proved to be in another direction. In October 1935 I went home by way of China where I visited Peking and the vicinity for about a month and continued on via the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

My first published work grew out of this year in the Far East. It included an article for the IPR quarterly on the Russo-Japanese fisheries for which I was paid $30, the first money I ever earned by writing; a review of Tsushima, a vivid history of the decisive battle of the Russo-Japanese War, a book I still remember well; and a little essay on the Japanese character which, to the astonishment of its unknown twenty-three-year-old author, made its way onto the imposing pages, alongside prime ministers, world bankers, and other pontiffs, of Foreign Affairs.

After a seven-year interval (focused on the Spanish Civil War and the menace of Hitler) my brief experience of Asia earned me a place on the Far East desk of the Office of War Information during World War II. As I was married with a child by this time, I stayed in the New York office whose operations were beamed to the allied and occupied countries of Europe. For the Far East desk it was a chronic battle against the Europe-oriented staff to get news of the war in Asia on the air at all. (Correspondents in China and Japan in the 1930s similarly fought to get their dispatches into print against the disinterest of editors and presumably of the public. I once accompanied an enterprising correspondent when he hired a number of Japanese laborers to wash down the great Buddha of Kamakura so that he could take pictures and write a story about the Buddhas supposed ceremonial bath.) At OWI we gained a place for the Far East news only because it was one of the aims of the operation to explain to our allies why so much American effort was engaged in the Pacific.

Since missionaries sons and serious students of Asia were all snapped up by OSS and OWI for assignments in the field, or in the Washington office where policy was made, I was one of the few staff members in New York with a personal if minuscule knowledge of the Far East. I was dragged out of bed to write the backgrounder on Tokyo on the night of our first long-range bomber attack in 1944 (for which no one had prepared). I wrote the backgrounders on the East China coast for the landing that never came, and on the Soviet Far East for the Russian entry against Japan that came only five days before the end. For some weeks I even took over the Indo-China desk in the absence of its normal occupant because, on the strength of a research paper I had once done for the IPR, I was the only person in the office who could say Laos, Cambodia, Cochin-China, Tonkin, Annam (the five states of Indo-China; no one then had ever heard of Vietnam) without hesitating.

For a while I also covered the Burma campaign in acrimonious rivalry with the military desk which considered Burma their turf while we at FE considered it ours. It was in the course of defending this territory that I followed the exploits of and became interested in General Stilwell. During the next twenty years the interest receded but remained a flickering ember that never died.

Meanwhile the restoration of the state of Israel after a gap of nearly 2,000 years struck me as an event unique in history and started me on my first book, Bible and Sword. Ending with the Balfour Declaration of 1918, this led me to The Zimmermann Telegram of 1917 which in turn led back to 1914 and The Guns of August, and that in turn to the social origins of the Great War in The Proud Tower. By the time that book was published, it was 1966. The American relation to Asia was now an importunate reality. No one needed to wash Buddhas to get it into the press.

Stilwell revived in my mind from a combination of reasons: because it offered what I had long been looking for, an important body of unpublished papers to work from; because his career made an ideal focus for a book on the American relation to China; and because when I discussed the subject with my eldest daughter and son-in-law, two highly educated, cosmopolitan young people, I was struck by the fact that they knew nothing about Americas past connection with China, but wanted to know. When I proposed an alternative subject that I had in mind at the time, they insisted that I must do the book on China, so I did.

I first approached the Stilwell family for access to the Papers in March 1967. Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 191145, was published in February 1971 two months before China opened its doors to the American Ping-Pong team, with Henry Kissinger not far behind. I can hardly claim to have foreseen this turn of events, much less its fortunate coincidence for my book, but when people ask how did I happen to choose China, I like to suggest that if a historian understands the past he will have acquired in the process a feel of the future.