This McDonnell F-4 Phantom II last flew with the U.S. Marine Corps.

Over a century has passed since Wilbur and Orville Wright took to the air in the first powered, controlled, heavier-than-air flight. Since that cold, windy day on the beach near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the airplane has transformed the world in astonishing ways. Originally a miraculous novelty, the airplane quickly became an indispensable tool for commerce, transportation, and war. In 1903 one could only imagine the possibilities of worldwide travel by air; today one cannot imagine traveling around the world in any other way.

The Smithsonian Institution has played a role in this dramatic story. Samuel Pierpont Langley, the third secretary of the Smithsonian, was a contemporary of the Wright brothers. His aerial experiments in the late 19th century paved the way for future pioneers, though his attempts at manned flight failed in 1903. The Smithsonian assisted the Wrights in 1899, and supported rocket pioneer Robert Goddard. In 1915 the Smithsonian helped create the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA), NASAs predecessor, which made critical discoveries leading to safer, more efficient flight.

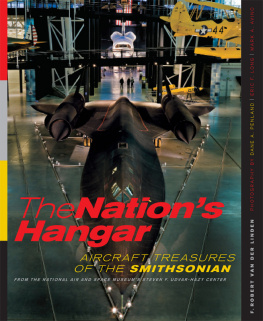

In keeping with the Institutions original mandate for the increase and diffusion of knowledge, the Smithsonian has led the way in preserving the history and technology of the artifacts of flight. From its first collection of Chinese kites in 1876, the nations collection of aeronautical artifacts has increased to over 33,000 objects encompassing virtually every aspect of aviation and spaceflight. As the collection expanded, the Smithsonians ability to display these treasures often failed to keep paceuntil now. Following the successful 1976 opening of the National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., momentum grew to construct an extension at a nearby major airport where our large aircraft and spacecraft could be displayed. This dream became a reality on December 15, 2003, with the opening of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center near Washington Dulles International Airport.

In addition to the 70 aircraft we exhibit on the Mall, we now display 200 aircraft and thousands of smaller, equally important artifacts in a magnificent new building over three times larger than the main museum. The aircraft exhibited here cover the entire history of flight and are some of the most significant examples of their types. This modern facility has enabled us to show the vast majority of our superb collection to the public, many objects for the first time. Now, with the completion of the Udvar-Hazy Center, we will have an outstanding preservation, restoration, and storage facility where all of the objects, including our priceless archival holdings, will reside in the latest climate-controlled environments, preserving our nations aerospace treasures for generations to come. It is indeed the Nations Hangar.

John R. Dailey

Director

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

The Lockheed SR-71 dominates this view of the interior of the Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center, flanked by the Curtiss P-40 on the left and the Vought F4U Corsair on the right, with the Space Shuttle behind it.

T he year 2011 marks a significant milestone in the history of the National Air and Space Museum (NASM). Since the opening of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in 2003, the Museum has actively worked to complete Phase Two of the project, namely the design and construction of a state-of-the-art preservation, restoration, and storage facility. After much hard work, this has come to pass. The facilities completed during Phase Two of the Udvar-Hazy Center construction replace the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility as the primary restoration and storage facility for NASM. Named after the Museums first curator, a visionary who collected most of the NASMs most influential and historically significant pieces, the Garber Facility had served the Museum for 60 years. It was time for a change.

Tucked away in Silver Hill, a corner of Prince Georges County, Maryland, seven miles from downtown Washington, the Garber Facility is rather nondescript. Surrounded by rundown strip malls and gas stations, a lone Polaris missile sits upright in the parking lot along Old Silver Hill Road, next to the local fire department. Visible behind the perimeter fencing is an unobtrusive sand-colored building with a large blue-and-gold seal of the Smithsonian Institution hanging prominently on the front wall. As inconspicuous as it may be, until the opening of the Udvar-Hazy Center this was the entrance to Valhalla for the aviation enthusiast.

Paul Edward Garber, aircraft collector without peer, almost single-handedly built the worlds finest collection of aeronautical artifacts in his 70-year career at the Smithsonian Institution.

There are 33 buildings at the Garber Facility, shared between NASM, the National Museum of American History, and other support organizations of the Smithsonian. Before the move to the Udvar-Hazy Center, NASM used 23 of these buildings. Eighteen were used for shipping and receiving, dense storage, and support functions, especially as an annex for NASMs Archives Division, and the other five contained thousands of aviation treasures. These buildings were accessible to the public for some time through specially guided tours, but in later years were closed to the public. With the completion of Phases One and Two of the Udvar-Hazy Center, the functions of many of these buildings are combined in one new massive, high-tech structure that features a restoration hangar four times larger than the one at the Garber Facility.

As extensive as the National Aeronautical Collection is, the problem of finding enough space to house the aircraft and spacecraft properly has dominated NASMs planning since the opening of the Museum building on the National Mall in 1976. Still flush with the excitement of opening what would immediately become the worlds most popular museum, the curatorial staff was painfully aware of the space limitations placed upon future collecting. The size of the facility at Silver Hill, even after it was refurbished and renamed in Paul Garbers honor, was insufficient to permit future growth.

Barring expansion at the Garber Facility, it would soon be impossible to collect any new military or commercial aircraft, as the size of even the smallest of these aircraft would strain the Museums ability to house and protect them correctly. For years the Museum had compensated for the lack of space by cobbling together off-site storage solutions and placing pieces of the collection on loan. Some of the larger artifacts, such as the Boeing 307 Stratoliner and the Boeing 367-80, were stored in the Arizona desert. Other large aircraft, such as the Curtiss NC-4, the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic, were placed on loan to museums around the country. The Space Shuttle